Check out the Build your own budget interactive analysis tool for a more comprehensive view of overall impacts.

The interactive analysis tool allows users to test various policy and parameter changes to see the impact on the Australian Government budget.

The modelling in Build your own budget underpins the projections and analysis contained in Beyond the budget, and users can replicate the scenario analysis contained in Beyond the budget for a more comprehensive view of overall impacts.

Overview

Beyond the budget 2023-24: Fiscal outlook and sustainability presents the Parliamentary Budget Office’s (PBO’s) independent projections for the Commonwealth’s fiscal position across the medium term (2027-28 to 2033-34). It also updates our analysis of long-term fiscal sustainability out to 2066-67.

The 2023-24 Budget showed a significant improvement in the economic and fiscal outlook for 2022-23 and 2023-24, compared to both the 2022-23 October Budget and our previous projections. Expected stronger nominal GDP growth has led to higher revenue and improved budget balances, and lower debt and interest costs across the medium term.

This better outlook has flowed through to improved longer term fiscal projections. In all but one of our scenarios, debt-to-GDP declines in the long term. Notwithstanding this improvement, there are structural challenges in the underlying budget position that will require government decisions to mitigate risks to fiscal sustainability.

The economic outlook, both domestically and internationally, is inherently uncertain. These risks require paying attention to both short term and longer-term challenges. One of these is to ensure that the mechanisms for collecting revenue and managing expenditure are efficient and flexible over time. Slowing productivity growth, the continued reliance on personal income taxes as the main source of revenue, and structural expenditure risks, such as ageing and climate change, remain key sources of fiscal pressure.

Our 8th set of independent medium-term projections are based on the policy settings, budget estimates, and economic parameters of the 2023-24 Budget. We use this information together with our models and professional judgement to project from 2026-27, the end of the budget forward estimates, to 2033-34, the end of the medium term.

Our projections are presented as our central case published in our new Build your own budget tool, which complements this report. The tool allows users to choose different parameter and policy settings from those presented in the Budget, and to review how these flow through to the fiscal position to the end of the medium term.

Data for all charts and tables in this report are also available from our Data portal. If you find this report useful or have suggestions for improvement, please provide feedback to feedback@pbo.gov.au.

1 How to read this report

Beyond the budget 2023-24: Fiscal outlook and sustainability presents the Parliamentary Budget Office’s (PBO’s) independent projections for the balance sheet, major fiscal aggregates, and revenue and expense categories across the medium term (2027-28 to 2033-34). It also includes our scenario analysis and assessment of the Australian Government’s long-term fiscal sustainability to 2066-67.

The report presents our annual medium-term budget outlook based on the policy settings, budget estimates, and economic parameters of the most recent Australian Government budget (see Appendix A). The medium-term projections presented here are based on the 2023-24 Budget. The results are compared to our Beyond the budget 2022-23, released in December 2022 and based on the 2022-23 October Budget.

The long-term fiscal sustainability analysis considers how the balance sheet could evolve after the end of the medium term (from 2034-35 onwards). While the projections to 2033-34 relate directly to the economic projections of the 2023-24 Budget, the longer-term fiscal analysis explores the question: 'If governments maintain budget balances that are similar to historical precedents across economic cycles, is the fiscal position likely to be sustainable across the long term?' To answer this, we focus on potential pathways for the debt-to-GDP ratio from 2034-35 to 2066-67, based on combinations of 3 key parameters: a budget balance (headline cash balance before interest payments), interest rates, and economic growth (nominal GDP).

As our framework for fiscal sustainability centres on the balance sheet, we present our medium-term outlook for the balance sheet and major aggregates first (chapter 2), followed by long-term fiscal sustainability scenarios (chapter 3). More detail on government revenue and expenses across the medium term is presented in chapters 4 and 5. Our projection methodology is summarised in Appendix A.

The underlying data series for all charts and tables are available in our Data portal.

This report can be read alongside our Build your own budget tool. The tool allows you to explore alternatives to the analysis we present here by adjusting various policy and economic parameters to test their impact on the Australian Government fiscal position.

Box 1: What is the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO)?

The PBO was established in 2012 to ‘inform the Parliament by providing independent and non partisan analysis of the budget cycle, fiscal policy and the financial implications of proposals’ (Section 64B of the Parliamentary Service Act 1999). We do this in 3 main ways:

- by responding to requests made by senators and members for costings of policy proposals or for analysis of matters relating to the budget

- by publishing a report after every election that provides transparency around the fiscal impact of the election commitments of major parties

- by conducting and publishing self-initiated work that enhances the public understanding of the budget and fiscal policy settings.

For further information and an introduction to our services, see Guide to the services of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO).

Our interactive dashboards are best viewed on larger screens/desktops.

Interactive charts and visualisations dashboard

This dashboard provides an interactive chart or visualization for each chart in this report. The dashboard is organized into chapters corresponding to the report’s structure.

We encourage you to explore the visualizations and interact with the data for a deeper understanding of the insights presented.

Our interactive dashboards are best viewed on larger screens/desktops.

2 Balance sheet and major fiscal aggregates

- This chapter presents our medium-term projections for the balance sheet and major fiscal aggregates, given the economic projections of the 2023-24 Budget.

- The substantial improvement to the economic outlook since the 2022-23 October Budget results in improved budget balances, lower debt levels and lower interest payments over the medium term.

- Gross debt is projected to fall from 35.8% of GDP in 2023-24 to 31.4% of GDP in 2033-34, despite continued budget deficits.

- Gross interest payments are projected to grow as bond yields rise, increasing from 0.8% of GDP in 2023-24 to 1.2% of GDP in 2033-34.

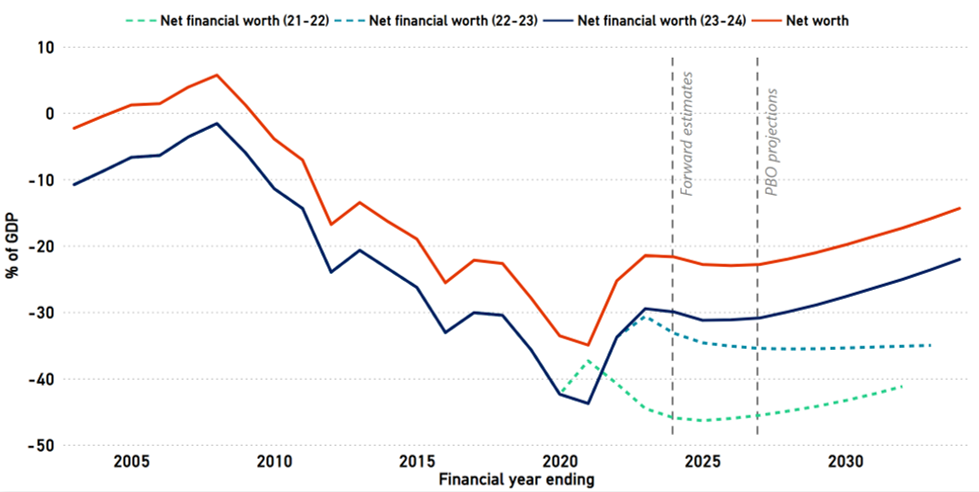

- Net financial worth is projected to improve from -30.0% of GDP in 2023-24 to -22.1% of GDP in 2033-34, reflecting the revised outlook for debt.

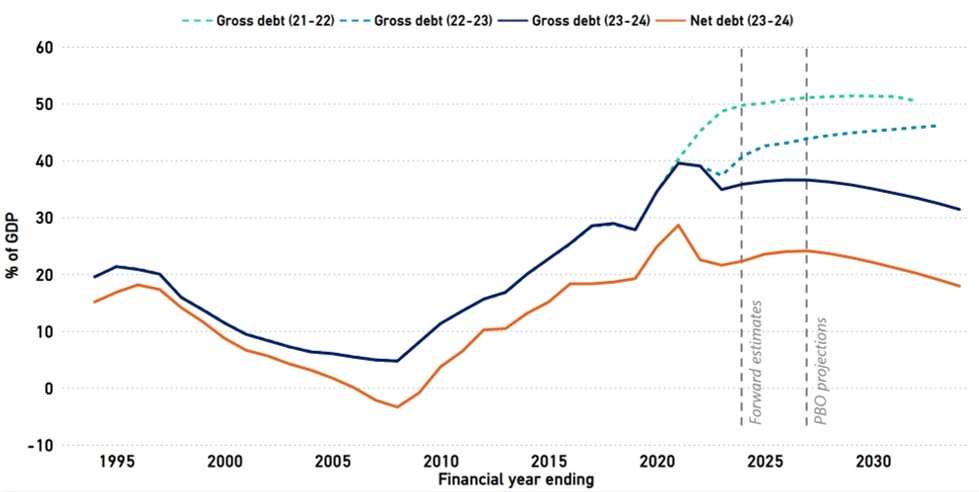

Gross debt as a percentage of GDP (Figure 2-1) is projected to be lower by the end of the medium term than in our previous projections and is no longer expected to exceed the 2020-21 peak. Previously, gross debt was projected to rise steadily through to 2032-33. The improvement is largely due to improved projected budget balances across the forward estimates, leading to lower debt and servicing costs (see Box 2).

Figure 2-1: Gross and net debt, 1993-94 to 2033-34

Note: 2021-22 and 2022-23 projections refer to the PBO’s previous Beyond the budget reports.

Note: 2021-22 and 2022-23 projections refer to the PBO’s previous Beyond the budget reports.

Source: 2021-22 Budget, 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Net debt, which adjusts the value of gross debt to account for the government’s financial assets, is projected to follow a similar trajectory.

Box 2: Why have the fiscal projections improved so dramatically?

The PBO’s fiscal projections based on the 2023-24 Budget are significantly improved compared to those based on the 2022-23 October Budget. This reflects changes in expected economic conditions, supported by government policy decisions. Economic conditions are inherently uncertain and volatile. Relatively small shifts in economic conditions can have dramatic effects on expected fiscal outcomes.

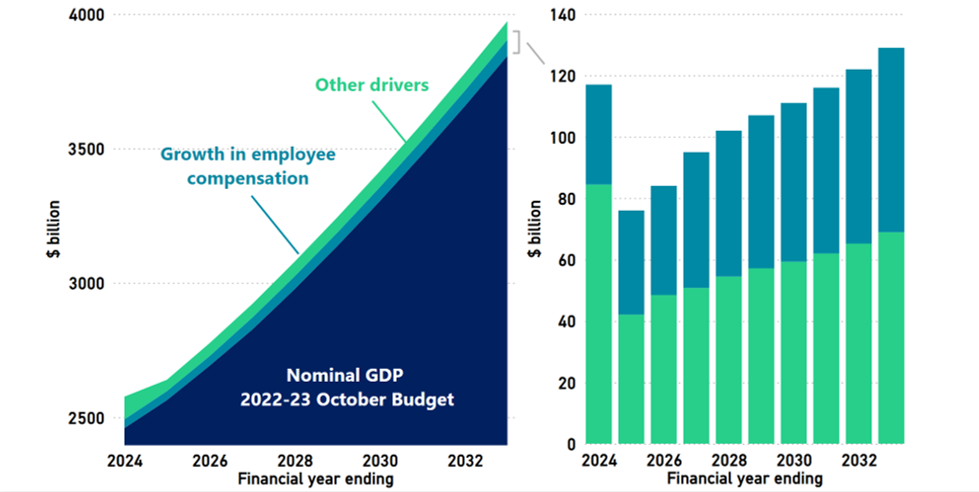

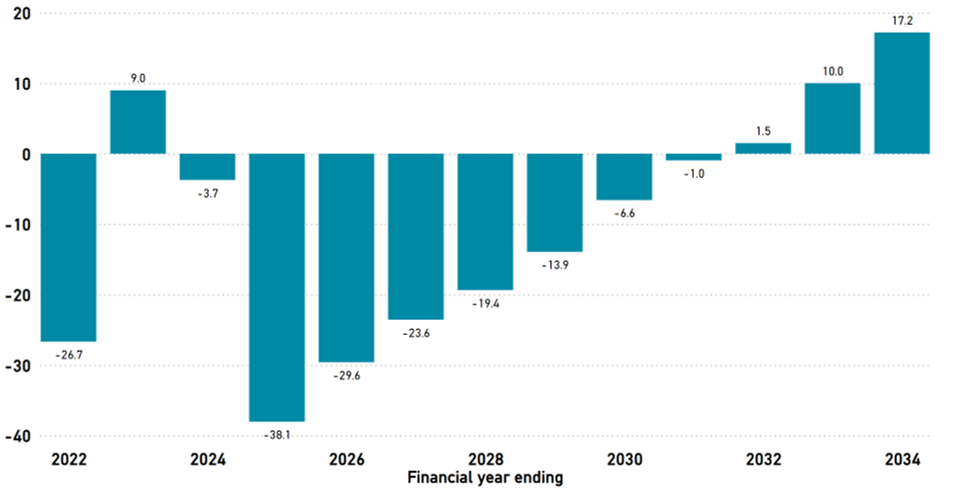

While expectations for economic production volumes are largely unchanged, a key shift in the economic projections from the 2022-23 October Budget to the 2023-24 Budget has been the increase in the expected level of nominal GDP (Figure 2-2), which flows through into stronger government revenue, improving the budget balance.

Forecast nominal GDP growth for 2022-23 has been revised from 8% at the 2022-23 October Budget to 10.25% at the latest Budget. A large portion of the gains were a result of global inflation and higher-than-expected commodity prices. While some of the increases are expected to unwind in 2024-25 as commodity prices ease,1 most of the additional GDP is expected to be permanent.

These improvements have a cumulative effect on the balance sheet aggregates, such as the government’s debt, as each year projects from a better starting point and is carried further into the future. The PBO’s analysis seeks to focus on longer-term challenges to the fiscal position, with a view to ‘seeing through’ the shorter-term volatility.

Figure 2-2: Change in nominal GDP projection from 2022-23 October Budget to 2033‑34 Budget, 2023-24 to 2032-33

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Gross and net interest payments are substantially reduced from the previous projections (Figure 2-3), as the better economic outlook flows through to improved budget balances and lower expected debt levels. Interest payments are projected to continue rising over the medium term as a percentage of GDP, reaching their highest level since 1999-00 in 2033-34, and returning to a trajectory similar to what was envisaged in our 2021-22 projections (September 2021), when gross debt was at its highest level and monetary conditions were more accommodating as part of the COVID-19 response.

Figure 2-3: Gross and net interest payments, 1993-94 to 2033-34

Note: Interest receipts, such as earnings on the government’s Future Fund, are subtracted from gross interest payments in the calculation of net interest payments. Interest receipts are also projected to increase across the period 2023-24 to 203334.

Note: Interest receipts, such as earnings on the government’s Future Fund, are subtracted from gross interest payments in the calculation of net interest payments. Interest receipts are also projected to increase across the period 2023-24 to 203334.

Source: 2021-22 Budget, 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

From October 2022 to May 2023, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) raised its overnight cash rate target from 2.6% to 3.85% to address inflationary pressures.2 Nevertheless, expected yields on government bonds declined between the 2022-23 October Budget and the 2023-24 Budget, as a result of financial markets lowering their expectations for the magnitude and timing of the peak in interest rates.

The budget incorporates assumptions about bond yields based on market expectations for future changes to bonds and interest rates. The 2022-23 October Budget assumed a weighted average cost of borrowing of 3.8% across the forward estimates (2022-23 to 2025-26), while the 2023-24 Budget assumed a weighted average cost of 3.4% across the forward estimates (2023-24 to 2026-27).3

As a result, when the government issues new bonds to finance future budget deficits or refinance matured debt, it will pay a lower rate of interest than previously assumed, which improves the fiscal balance.

Figure 2-4 shows the effect of bond yields on interest payments by comparing projections from the 2022-23 October Budget and the 2023-24 Budget. This, along with the lower level of net debt, helps illustrate why our projections for interest payments have moderated relative to our 2022-23 projections (Figure 2-3).

Figure 2-4: 2022-23 October Budget and 2023-24 Budget – bond yields, net debt, and net interest payments

Note: estimates for net interest payments are published in the 2022-23 October Budget and 2023-24 Budget only for the forward estimates and the final year of the medium term (2032-33 and 2033-34 respectively).

Note: estimates for net interest payments are published in the 2022-23 October Budget and 2023-24 Budget only for the forward estimates and the final year of the medium term (2032-33 and 2033-34 respectively).

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

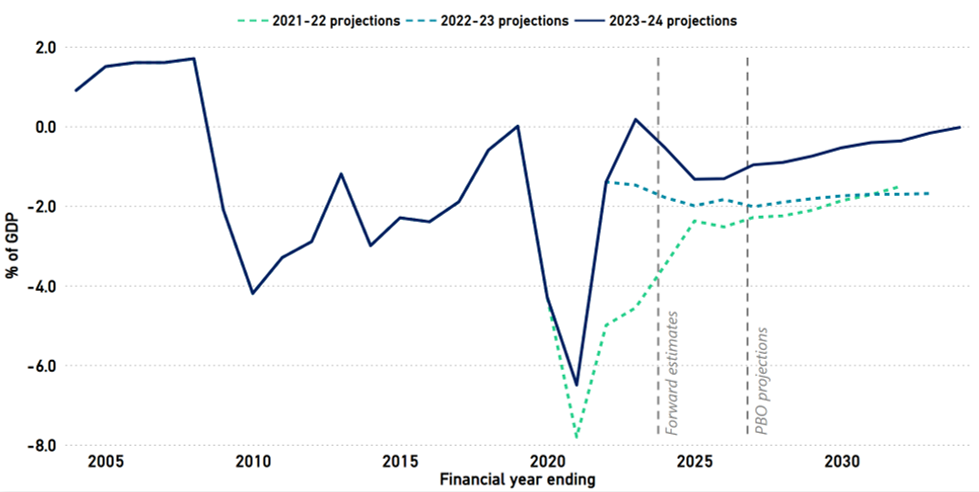

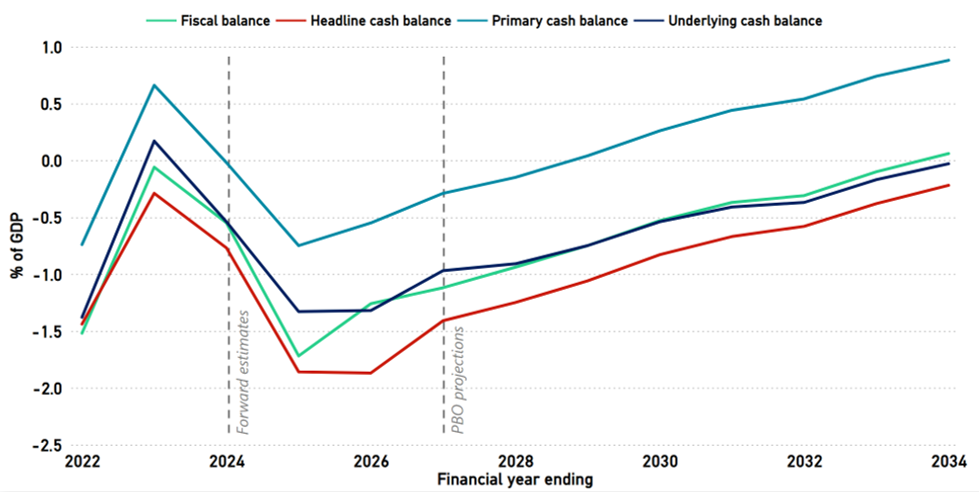

The improved economic outlook leads to projected surpluses in the primary and fiscal balances by the end of the medium term. The underlying cash balance is expected to be in surplus in 2022-23 before returning to deficit through the forward estimates and improving as a share of GDP to balance by the end of the medium term (Figure 2-5).

Figure 2-5: Underlying cash balance, 2003-04 to 2033-34

Source: 2021-22 Budget, 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Source: 2021-22 Budget, 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

The underlying cash balance is one of several ‘fiscal aggregates’ used to assess the budget position. As each aggregate has a different focus, it can be useful to examine different aggregates when assessing the budget position.

The primary cash balance, fiscal balance, and headline cash balance (see Appendix A for a description of these and other budget balances) are commonly used in conjunction with the underlying cash balance (Figure 2-6).

- The primary cash balance, which subtracts net interest payments from the underlying cash balance,4 is projected to be in surplus from 2029-30.

- The fiscal balance is projected to be slightly stronger than the underlying cash balance in 2033-34, reaching a surplus of 0.1% of GDP by the end of the medium term. While the fiscal balance tends to lead the underlying cash balance, both aggregates generally follow the same trajectory.

- Compared to the other measures, the headline cash balance is projected to show the largest deficit and also the most improvement across the medium term. This pattern largely reflects policies (such as student loans, Clean Energy Finance Corporation loans and investments, and equity injections) that have a negative impact on the headline cash balance but little impact on other indicators of the budget balance.5

Figure 2-6: Budget aggregates, 2021-22 to 2033-34

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Net financial worth and net worth (Figure 2-7) are projected to improve as a percentage of GDP across the medium term, largely due to the same factors that affect net debt.

Figure 2-7: Net financial worth and net worth, 2003-04 to 2033-34

Note: Net financial worth; 2021-22 projections; 2022-23 projections; 2023-24 projections, and Net worth 2023-24 projections.

Note: Net financial worth; 2021-22 projections; 2022-23 projections; 2023-24 projections, and Net worth 2023-24 projections.

Source: 2021-22 Budget, 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

3 Fiscal sustainability

- This chapter explores how the balance sheet could evolve under a range of assumptions and whether the fiscal position is likely to be sustainable over the long term to 2066-67.

- Our scenarios show that the longer-term fiscal position is significantly stronger than presented in our 2022-23 analysis, largely owing to the upgraded short-term economic and fiscal outlook. The long-term debt-to-GDP ratio is lower in all scenarios, reflecting improved budget balances and lower interest payments on debt.

- The fiscal position is sustainable in most scenarios considered here. This means that future governments should be able to keep debt-to-GDP relatively stable through interventions on a similar scale to what we have seen in the past.

- However, structural risks to the budget remain, including the tax mix, ageing population and the climate change transition, that may increase the extent to which governments would need to intervene to keep the fiscal position sustainable.

Judgements about fiscal sustainability relate to the long term. In this analysis, fiscal sustainability refers to the government’s ability to maintain its long-term fiscal policy settings indefinitely without the need for major remedial policy interventions. This means that governments need to continue to act but that, in general, historical approaches to borrowing and repaying debt can be maintained, while keeping taxation and spending within reasonable and expected bounds. In contrast, the government’s Intergenerational Report projects on the basis of no future policy changes, resulting in projections that are usually more pessimistic than those presented by the PBO.

We consider the fiscal position to be sustainable if the debt to GDP ratio is expected to be stable or trend downwards over the long term. Such circumstances provide governments the fiscal space to pursue their long-term policy objectives and to support sustainable economic growth. It allows flexibility for governments to respond to changes in economic conditions, including downturns, either through automatic or discretionary mechanisms.

The long-run trajectory for the debt-to-GDP ratio is driven by 3 parameters: the budget balance (headline cash balance before interest payments); the prior stock of debt and the interest rates that apply to this debt; and economic growth (nominal GDP).

The budget balance does not necessarily need to be zero or in surplus to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. If the rate of economic growth exceeds the rate of interest on debt, debt-to-GDP can be reduced with sufficiently small budget deficits. Accordingly, budget deficits can be consistent with a fiscally sustainable position.

A sustainable position also does not mean the debt-to-GDP ratio will not increase at times, especially in response to large unforeseen economic shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In this sense, it is not necessarily the level of debt that determines if the fiscal position is sustainable, but whether, on average, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to remain stable or to trend downwards over the long term.

By comparison, the fiscal position may not be sustainable if the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to trend upwards over the long term. In such circumstances, major interventions could be needed to reduce deficits and keep debt broadly stable as a percentage of GDP.

In our fiscal sustainability analysis, we examine 27 possible scenarios for the debt-to-GDP ratio over a 40-year period. Each scenario reflects variations in the 3 parameters identified above – interest rates, economic growth, and the budget balance – consistent with low, middle, and high ranges throughout history. Here, we refer to these variations as ‘cases’. For example, one scenario might combine our middle case for the budget balance, our upside case for interest rates, and our downside case for GDP growth. Our cases for the budget balance, interest rates, and economic growth are described below.

Interest rates are similar to their recent levels in most scenarios.

- In our middle case, interest rates are at 4.5% by 2066-67, reflecting assumptions for long-term bond yields.

- In our upside and downside cases, interest rates vary by ±0.6 percentage points (ppt) from our middle case by 2066-67.

Our GDP scenarios incorporate different paths for important drivers of growth.

- Future economic growth depends on growth in the population, productivity, and labour force participation.

- For variables that may change significantly over time, such as productivity, we implicitly account for peaks and troughs by looking at their long-run historical averages. For population growth, which incorporates the impact of ageing, we take projections from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- In our middle case, nominal GDP growth reaches 4.5% by 2066-67. In our upside and downside cases, GDP growth reaches approximately ±0.6 ppt from our middle case by 2066-67, reflecting deviations in both productivity and population growth.

The upside and middle scenarios assume varying levels of surplus could be achieved from 2034-35 to 2066 67, while the downside case considers ongoing deficits.

- This is driven by a balanced budget position being achieved by 2033-34 while economic growth and modest interest rates build towards surpluses over the long term.

- In our middle case, modest surpluses are achievable from 2034-35 through to 2066-67. This compares to expected deficits in our previous report.

- Our downside case shows ongoing deficits from 2034-35 to 2066-67.

- The upside case shows the possibility of gradually strengthening surpluses from 2034-35 through to 2066 67.

Each of our scenarios represent a possible future trajectory for the debt-to-GDP ratio, but we do not make any judgement as to which scenario is most likely. For instance, our middle scenario should not be considered as a baseline or most likely trajectory. Instead, we are illustrating what the path could be under a range of plausible economic and policy conditions.

For example, if governments were to run larger deficits than expected over the medium term to 2033-34, the sustainability of the fiscal position would rely to a greater extent on favourable economic conditions in terms of GDP growth and interest rates. In a scenario where GDP growth is persistently low and interest rates remain higher than expected, this would require more fiscal policy interventions from governments to ensure stability in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Importantly, the best and worst scenarios represent combinations of interest rates and economic growth that would be unlikely to persist for an extended period of time. For example, should economic growth slow to the rate assumed in the worst scenario, the RBA may respond by lowering interest rates, offsetting the impacts on the budget balance. These scenarios are intended to illustrate that the budget is sustainable even assuming unprecedented combinations of long-term economic growth, interest rates and budget balances.

By building our scenarios around historical averages, we have implicitly captured the impact of future economic shocks and policy changes, to the extent that these are of a similar magnitude to those of the past. However, if future economic shocks were larger or more frequent than historical shocks, or if long-term structural shifts meant that GDP growth rates were much lower than they have been historically, this would make it more difficult for Australia to maintain a fiscally sustainable position.

Some structural shifts may be largely predictable, such as the impact of the ageing population, but there may also be shifts or shocks that are highly uncertain, such as those relating to climate change. While some policies to reduce emissions may affect productivity in a way that can be anticipated, the frequency and impact of extreme weather events due to climate change is much harder to predict. While not explicitly modelling potential climate change impacts, our upside and downside scenarios aim to capture some of this uncertainty.

For more information on the framework we use to assess fiscal sustainability, see our Fiscal sustainability report. Our interactive visualisations of fiscal sustainability are available in the following section of this report.

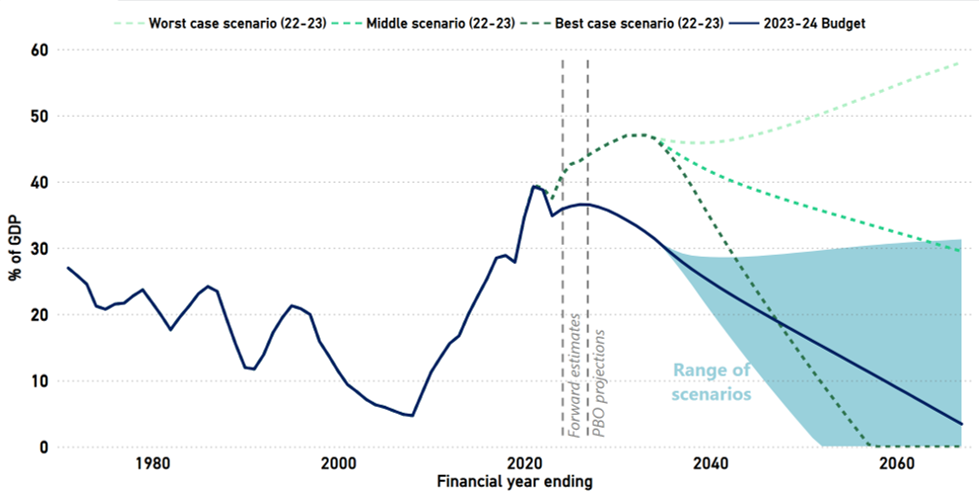

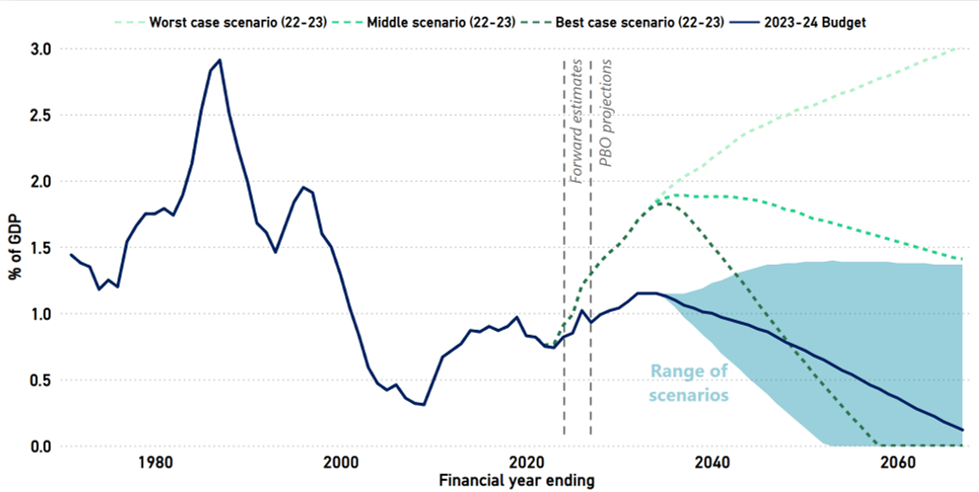

Table 3-1 shows our middle, upside, and downside cases. The results of all 27 scenarios are shown in Figure 3-1. Interest payments under each scenario are shown in Figure 3-2.

Table 3-1: Cases for middle, best and worst scenarios8

In all except one extreme long-term scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to trend downwards over the long term. This suggests that the fiscal position is likely to be sustainable in all but one scenario.

Figure 3-1: Gross debt, 1970-71 to 2066-67

Note: Dashed lines refer to PBO projections published in the 2022-23 Beyond the budget report for low, medium, and high GDP growth scenarios.

Note: Dashed lines refer to PBO projections published in the 2022-23 Beyond the budget report for low, medium, and high GDP growth scenarios.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Figure 3-2: Interest payments, 1970-71 to 2066-67

Note: Dashed lines refer to PBO projections published in the 2022-23 Beyond the budget report for low, medium, and high GDP growth scenarios.

Note: Dashed lines refer to PBO projections published in the 2022-23 Beyond the budget report for low, medium, and high GDP growth scenarios.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

In our middle scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to trend downwards across the entire scenario period. Compared to the middle scenario in our 2022-23 analysis, the downwards trajectory is faster, and the debt-to-GDP ratio is lower in 2066-67. This pattern primarily reflects lower budget deficits across the medium term flowing across the scenario period. Interest payments follow a similar trajectory to the debt-to-GDP ratio and are lower than the middle scenario in our 2022-23 analysis, reflecting that our central case for debt on which interest will need to be paid is lower.

In our best scenario, characterised by historically high GDP growth, low interest rates, and a gradual return to stronger budget surpluses from 2034-35 to 2066-67, the debt-to-GDP ratio trends sharply downwards and reaches nil by 2051-52. Interest payments also reach nil by 2051-52, reflecting the elimination of debt, and have a lower peak compared to our 2022-23 analysis.

In our worst scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio trends upwards over the scenario period, though at a slower rate than in our 2022-23 analysis. This scenario is characterised by adverse economic conditions, with lower GDP growth and higher interest rates. Interest payments are stable even as the debt-to-GDP ratio is trending upwards and are lower than in our worst scenario in our 2022-23 analysis, again reflecting the recent moderation in expectations for the level of interest rates.

Each scenario is based on historical averages, which means they implicitly incorporate the peaks and troughs of economic cycles. For instance, periods of weaker GDP growth are balanced by periods of stronger growth, and periods of large budget deficits are offset by periods of smaller deficits or surpluses. While we do not explicitly model economic shocks, such as those caused by financial crises, pandemics or climate change, our downside scenarios may be thought of as those in which such events are occurring more frequently than suggested by the long-term historical experience.

Concerted efforts to build fiscal buffers (that is, to lower the level of debt) can provide more flexibility to governments when responding to such events. Medium-term fiscal strategies are a key tool in building fiscal buffers and managing fiscal policy expectations. They can effectively extend the horizon for fiscal policy beyond the forward estimates and into the medium term, promoting fiscal discipline and accountability.

Importantly, a fiscally sustainable position does not mean governments do not need to address structural budget issues or to repair the budget after a downturn, but rather that the magnitude of fiscal policy interventions would be comparable to examples previously seen in Australia. The longer that governments wait to address structural issues, the larger the policy change required to keep the fiscal position sustainable.

As circumstances change, policies must adapt to ensure they continue to reflect the values and social expectations of the society they represent. Slower policy responses can lead to higher costs in the future, and more constrained choices. In the context of an ageing population, Australia will need to confront the implications and suitability of the current tax mix for intergenerational equity and, ultimately, for fiscal sustainability.

As Australia’s population ages, higher costs are involved in delivering the health and aged care that our society expects in order to maintain the quality of life of older Australians. Of the 7 fastest growing major payments in the 2023-24 Budget, all except for defence and interest payments directly relate to health and ageing. See the PBO’s Australia’s ageing population report for a detailed analysis of the impacts of an ageing population on revenue and spending.

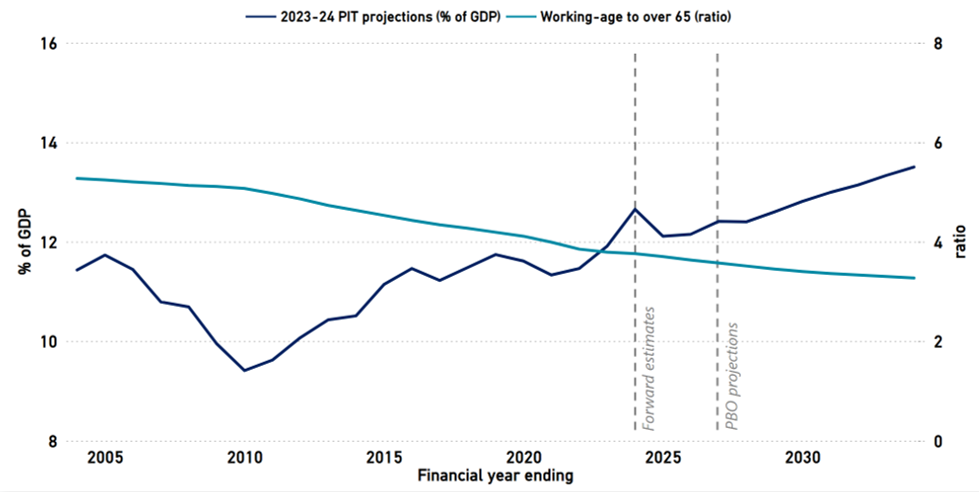

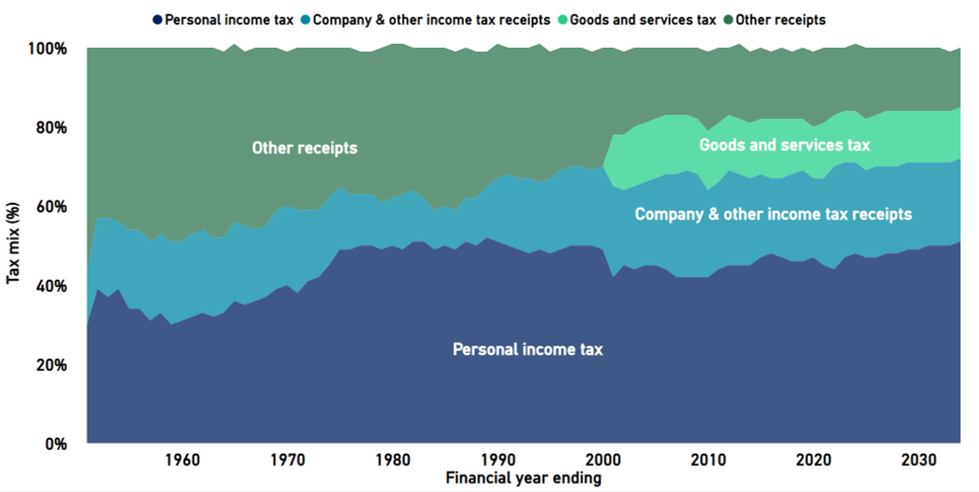

At the same time, our system of taxation continues to increase its reliance on personal income tax. Its contribution to revenue is projected to increase as a percentage of GDP and is largely borne by the working age population. As the ratio of working age people to older people shrinks, this translates to a higher tax burden for the working age population, as shown in Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3: Australia’s personal income tax and working age population ratio, 2003-04 to 2033-34

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

For the current tax mix, with its high dependence on personal income tax, there is a trade-off between providing sufficient support for the ageing population and maintaining intergenerational fairness for younger Australians whose primary income is wages.

Figure 3-4 shows the changes in personal income tax receipts as a share of total receipts over time. Following the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax in July 2000, personal income tax receipts fell from 49.4% of total receipts in 1999-00 to 42.2% in 2000-01. This fall has been almost entirely unwound with personal income tax receipts projected to reach 48.4% of total receipts by the end of the forward estimates.

Figure 3-4: Australia’s tax mix, 1950-51 to 2033-34

Note: Figures beyond the forward estimates period are PBO projections; tax receipts are projected forward based on the growth in tax revenue from 2027-28 to 2033-34.

Note: Figures beyond the forward estimates period are PBO projections; tax receipts are projected forward based on the growth in tax revenue from 2027-28 to 2033-34.

Source: 2023-24 Budget, Historical Fiscal Data and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

While all taxes involve trade offs, a tax mix with less emphasis on personal income tax is likely to be more resilient to some economic shocks such as changes in the labour force. A lower reliance on personal income tax can also distribute the tax burden across a broader base, to include assets or consumption.

In discussions on the overall structure of tax sources, policymakers consider several factors, including sustainability, efficiency, and equity implications.10

These principles of taxation are distinct but related. For the tax system to be sustainable, it needs to be resilient to changes in society over time, while remaining flexible to allow adaptation as required. More efficient taxes, or those which have less of a negative impact on economic growth, improve the sustainability of taxation because people and businesses are not able to change their behaviour over time in a way that minimises their tax burden. Similarly, ensuring an equitable system strengthens the legitimacy of the system as a whole.

Intergenerational considerations, together with projections of increasing expenditure pressures to meet the needs of the ageing population, suggest that Australia’s concentrated tax mix may pose a risk to the long-term sustainability of the tax system. Ensuring a robust system for the future will require careful consideration of the impact of the tax mix on all population cohorts.

There are other fiscal risks to the budget over the medium term, from specific policy areas such as National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) expenditure, through to broader risks to the economy such as the slowing overall rate of productivity, climate change and geo-political uncertainty. These risks necessitate strategies that prioritise building fiscal buffers, to enable governments to respond if key risks materialise.

NDIS costs have expanded rapidly since its inception as more people enter the scheme, and as average plan costs increase. The 2023-24 Budget includes an 8% target expenditure growth rate for the NDIS from 1 July 2026. NDIS spending is discussed in more detail in section 5.3.

Another significant fiscal risk is climate change. Climate change has multiple effects on government finances, including through meeting the costs of natural disaster recovery, direct and indirect productivity impacts and by changing infrastructure investment requirements. Governments can also come under pressure to adopt policies that artificially suppress price signals, for instance, by underwriting insurance for areas that become more prone to natural disasters, thus keeping the insurance premiums low. Such policies can limit the adaptation that individuals and businesses take in response to climate change (for instance, by relocating to less risky areas) and result in additional fiscal risks for the government. In the 2023-24 Budget, the government reported $4.6 billion in new climate-related expenditure, further to the $24.9 billion in new climate-related spending announced in the 2022-23 October Budget.12

Beyond expenditure risks, climate change also poses risks to the sustainability of government revenues. Climate change will increasingly impact business operations, investment decisions and ultimately profitability, which will impact company tax collections.

Australia’s commodities exports, agricultural production, and financial sectors are particularly exposed to the risks posed by climate change. The substantial contribution of these sectors collectively to government revenues highlights the degree to which climate change presents a fiscal challenge to policymakers. Australia’s substantial infrastructure spending pipeline presents a further fiscal risk, with potential cost overruns and new investments a source of fiscal pressure.

Defence expenditure is projected to increase in line with the government’s commitments to the AUKUS trilateral partnership arrangement and to implement the latest Defence Strategic Review. In the 2023-24 Budget, defence is projected to be the fourth fastest growing expenditure area across the period 2023-24 to 2033-34, although as a percentage of GDP defence expenditure is projected to remain relatively stable (Box 3).13

Box 3: Developing your own scenario analysis

The PBO’s Build your own budget tool allows you to test the impact of your own policy or economic assumptions on the fiscal position.

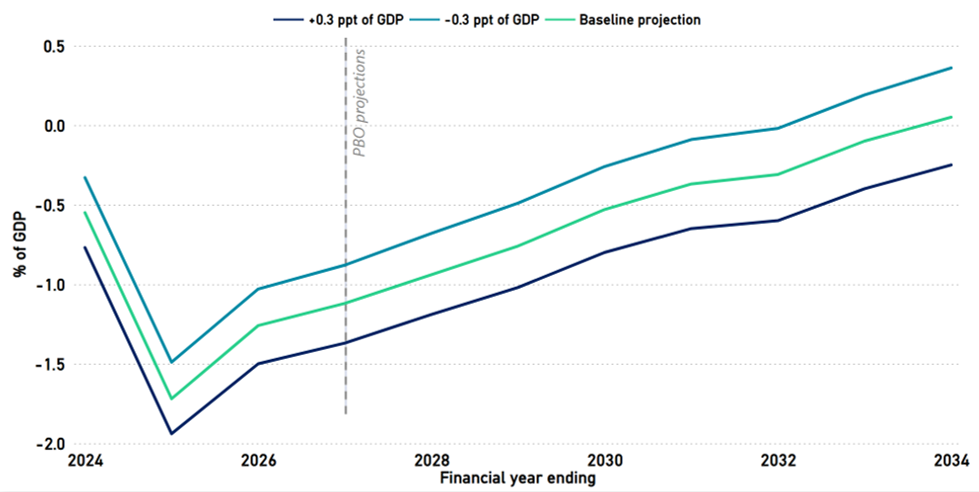

One such feature is the ability to set a target level for expenditure on defence as a percentage of GDP. Figure 3-5 below presents 3 scenarios for the fiscal balance across the period 2023-24 to 2033-34.

1. Defence expenditure targeted at 2.4% of GDP, an increase of 0.3% on the current baseline.

2. Defence expenditure targeted at 2.1% of GDP, consistent with the current baseline.

3. Defence expenditure targeted at 1.8% of GDP, a decrease of 0.3% of the current baseline.

In the baseline scenario, the fiscal balance reaches 0.1% of GDP by the end of the medium term, while in the increased defence expenditure scenario, the fiscal balance is projected at -0.3% of GDP by the end of the medium term. In the reduced defence expenditure scenario, the fiscal balance is projected to reach 0.4% of GDP by the end of the medium term. This example serves to illustrate the sensitivity of fiscal projections to changes in expenditure.

Figure 3-5: Defence expenditure impacts on fiscal balance, 2023-24 to 2033-34

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

4 Revenue

- This chapter presents our projections for the individual revenue categories that determine the budget aggregates.

- Total revenue is projected to increase from 26.4% of GDP in 2023-24 to 26.6% of GDP in 2033-34, largely driven by personal income tax due to bracket creep and superannuation taxes due to higher employer contributions.

- Company tax revenue is projected to decrease from 5.1% of GDP in 2023-24 to 4.6% of GDP in 2033-34 as commodity prices return to trend.

- Goods and services tax (GST) revenue is projected to remain stable as a percentage of GDP across the medium term, as are most other revenue categories.

- The aggregate average personal income tax rate is projected to increase across the medium term to a record high of 27%, even after Stage 3 of the Personal Income Tax Plan is implemented.

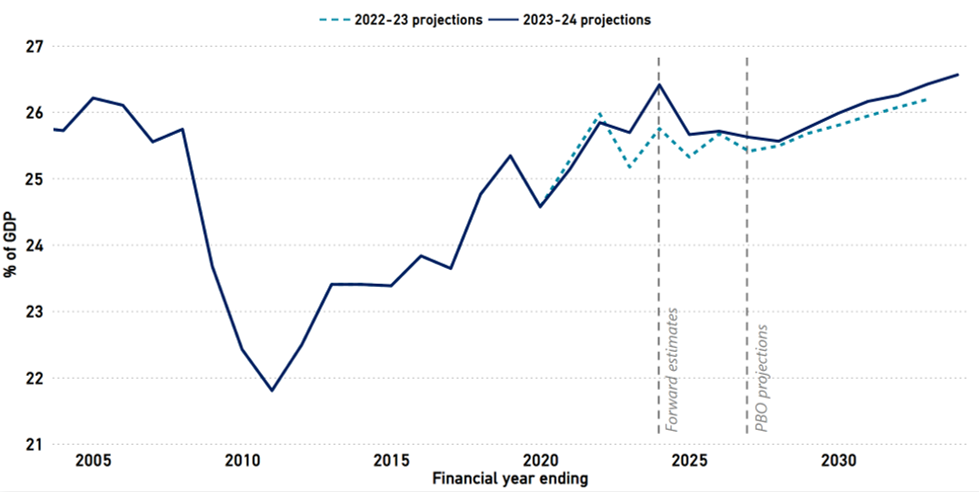

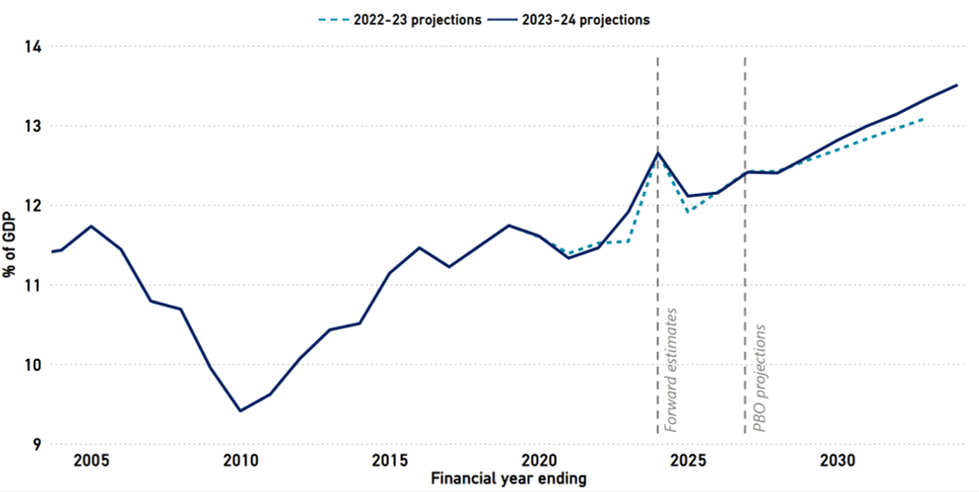

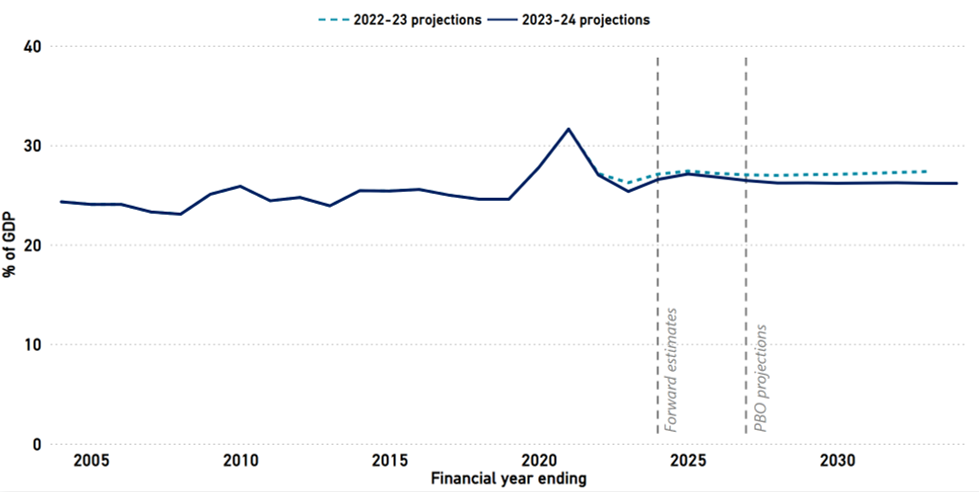

Total revenue (Figure 4-1) is projected to increase as a percentage of GDP across the medium term. Compared to our 2022-23 projections, total revenue is expected to be higher in 2032-33, largely due to upwards revisions to personal income tax collections.

Figure 4-1: Total revenue, 2003-04 to 2033-34

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Revenue measures in the 2023-24 Budget were estimated to improve the budget position by $19.9 billion across the forward estimates.

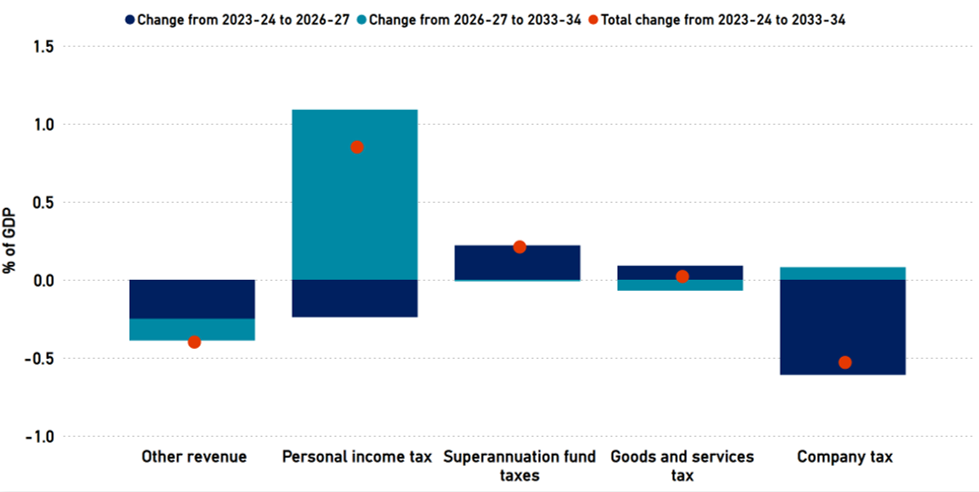

Personal income and superannuation taxes account for most of the increase in total revenue across the medium term (Figure 4-2). This reflects strong employment growth and high participation rates as well as nominal income growth and increases to the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) rate. As at 1 July 2023, the SG rate will be 11.0% and is legislated to increase by 0.5 percentage points each financial year until it reaches 12% in 2025-26. For personal income tax, bracket creep is also a strong contributor, as discussed in section 4.3 – Personal income tax and bracket creep.

While the increase in the SG rate leads to an increase in revenue from superannuation taxes, it is expected to have an overall net negative impact on total tax revenue. This is because higher employer superannuation contributions are typically borne by the employee through slower growth in salaries and wages.15

Superannuation contributions are taxed at a concessional rate (generally 15%), while salaries and wages are taxed at higher rates, on average, under the personal income tax system. For comparison, the aggregate average marginal tax rate on personal income is estimated to be 26.1% in 2022-23. For further information on the taxation of superannuation in Australia, refer to the PBO's Budget Explainer, How is super taxed?

Figure 4-2 shows the programs with the largest movements in revenue as a percentage of GDP, split between changes over the forward estimates period (2023-24 to 2026-27) and the medium-term (2026-27 to 2033-34).

Figure 4-2: Changes in tax revenue, 2023-24 to 2033-34

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

The contribution from company tax collections decreases as a percentage of GDP over the forward estimates as the temporary boost from higher commodity prices unwinds. Company tax revenue is then projected to remain relatively flat as a percentage of GDP through the medium term. GST revenue is also projected to remain relatively flat across the medium term as a percentage of GDP, as are most other revenue categories.

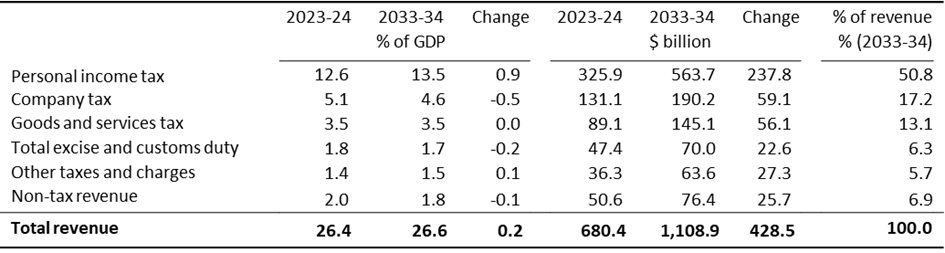

Table 4-1 shows the revenue sources with the largest movements between 2023-24 and 2033-34 as well as the change as a percentage of GDP. As a contributor to total revenue growth, personal income tax overshadows any other types of revenue as a share of GDP.

Table 4-1: Comparison of revenue estimates (top 6)

Note: 'Change' refers to the total change between 2023-24 and 2033-34. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Note: 'Change' refers to the total change between 2023-24 and 2033-34. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

For a full comparison of revenue estimates, refer to Table B-1 in Appendix B.

Personal income tax revenue (Figure 4-3) is projected to increase as a percentage of GDP over the medium term due to strong employment conditions and bracket creep. Bracket creep occurs when average tax rates rise due to nominal income growth in a tax system with fixed thresholds.

Figure 4-3: Personal income tax revenue, 2003-04 to 2033-34

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

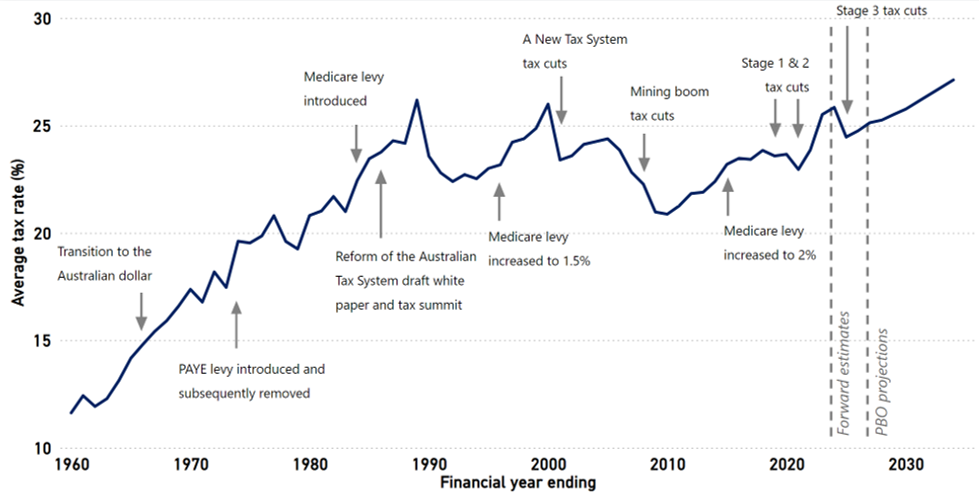

Stage 3 tax cuts have been factored into our projections since 2019-20 and are legislated to commence in 2024-25. The tax cuts are estimated to decrease personal income tax revenue by 0.5% of GDP in the same year. Our projections are consistent with announced government policy. We do not assume any personal income tax cuts following the Stage 3 cuts in 2024 25. Australia’s personal income tax system typically results in an increasing tax rate over time in the absence of government intervention. This is because the tax rate thresholds are not indexed automatically, so as nominal wages rise, tax rates also rise – this is known as bracket creep.

Without further changes, bracket creep is projected to increase the average tax rate for individuals from around 25% in 2026-27, close to the historical high, to 27% by the end of the medium term, well above historic highs (Figure 4–4). The sensitivity of the fiscal balance to changes in personal income tax rates is investigated further in Box 4 below.

Figure 4-4: Aggregate average personal income tax rate, 1960-61 to 2033-34

Note: For consistency across time, net tax before 2000-01 is calculated before allowance for franking credits. Data for non-taxable individuals is unavailable prior to 1978-79. The net tax rate prior to 1978-79 assumes that taxable income for non-taxable individuals has the impact of reducing the average tax rate by around 0.7 percentage points, the median amount from 1978-79 to 1987-88.

Note: For consistency across time, net tax before 2000-01 is calculated before allowance for franking credits. Data for non-taxable individuals is unavailable prior to 1978-79. The net tax rate prior to 1978-79 assumes that taxable income for non-taxable individuals has the impact of reducing the average tax rate by around 0.7 percentage points, the median amount from 1978-79 to 1987-88.

Source: ATO Taxation Statistics, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Bracket creep has played an important role in fiscal consolidation after major downturns in the past. For example, both the average tax rate and total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP were relatively low after the 1990s recession and the global financial crisis (GFC), but bracket creep allowed both ratios to gradually increase, improving the budget position.

Reliance on bracket creep can have other effects on the budget. For example, higher average tax rates can magnify the economic impacts associated with personal income tax. For some people, especially those on relatively low incomes, bracket creep can reduce workforce participation. At higher incomes, bracket creep can strengthen incentives for tax planning and structuring.17

A high reliance on personal income tax can also leave government revenues vulnerable to changes in the composition of the economy. For example, the ageing population is expected to result in a decline in net taxpayers as a share of the total population. Many retirees pay little to no personal income tax because they have lower incomes and access to age-related tax concessions.

These risks can compound over time, and future governments may also face pressures to offset the impacts of bracket creep. Accordingly, there are important choices for governments to make between fiscal consolidation aided by bracket creep, and minimising the risks associated with relying on a single source of revenue.

More information on how personal income tax projections compare to history can be found in our Budget bite, Trends in personal income tax.

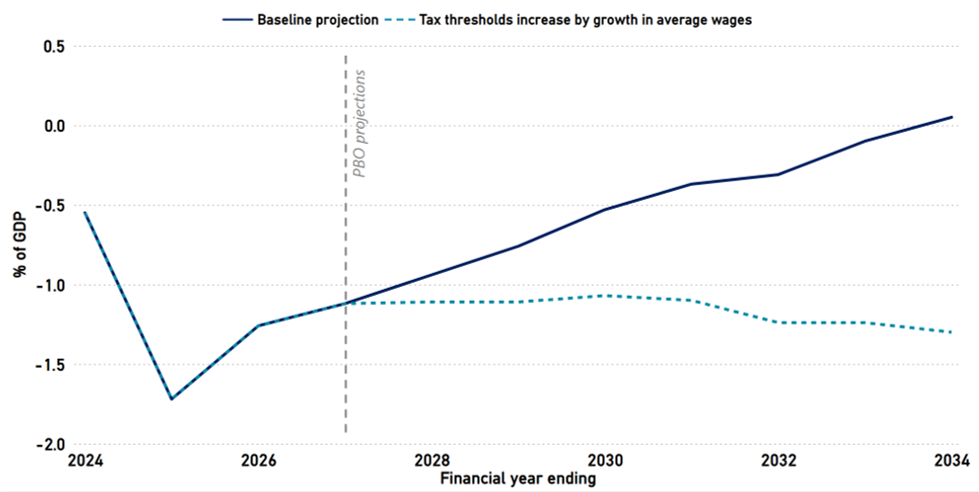

Box 4: The impact of adjusting for bracket creep

Governments have historically provided regular personal income tax cuts to compensate for the effects of bracket creep. The last time personal income tax cuts were more than 4 years apart was in the 1960s.19

Our Build your own budget tool allows you to test the impact of different tax brackets and rates. Figure 4-5 below presents two scenarios for the fiscal balance across the period 2023-24 to 2033-34.

1. Baseline projection (including Stage 3 personal income tax cuts), where personal income tax revenue as a percentage of GDP increases from 12.6% in 2023-24 to 13.5% by 2033 34.20

2. Baseline projection plus personal income tax thresholds increased in line with average wages from 2027-28. Under this scenario, personal income tax revenue as a percentage of GDP decreases from 12.6% in 2023-24 to 12.3% by 2033-34.21

In the baseline scenario, the fiscal balance improves and reaches 0.1% of GDP by 2033-34. In the alternative scenario where tax thresholds are adjusted for bracket creep, budget deficits continue at around 1.0% of GDP. This highlights the judgements that policy makers have to make about using bracket creep to manage the financial position, or returning bracket creep to individuals through tax cuts.

Figure 4-5: Projected fiscal balance, with and without returning bracket creep

Note: Calculated using the PBO’s Build your own budget tool.

Note: Calculated using the PBO’s Build your own budget tool.

Source: PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

5 Expenses

- This chapter presents our projections for the main expense categories that determine the budget aggregates.

- Total expenses are projected to decrease from 26.5% of GDP in 2023-24 to 26.1% of GDP in 2033-34, largely driven by a reduction in interest expenses on debt and efforts to constrain the growth in expenditure on the NDIS.

- Even with the measures to constrain expenditure, total NDIS costs are projected to increase from 1.6% of GDP in 2023-24 to 2.3% of GDP in 2033-34 with more people projected to enter the scheme and average costs expected to rise.

- Interest expenses are projected to increase from 0.9% of GDP in 2023-24 to 1.1% of GDP in 2033-34, attributed to rising interest rates and an increasing level of gross debt.

- Expenditure on aged care is projected to increase from 1.4% of GDP in 2023-24 to 1.5% of GDP in 2033-34, reflecting increased demand for services as the population ages as well as structural reforms to the aged care system.

Total expenses (Figure 5-1) are projected to decrease as a percentage of GDP across the medium term. Compared to our 2022-23 projections, total expenses are expected to be lower in 2032-33, largely because of downwards revisions to expenditure on interest costs and the NDIS.

Figure 5-1: Total expenses, 2003-04 to 2033-34

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

While total expenditure as a percentage of GDP has fallen relative to the 2022-23 October Budget, expenditure policy measures in the 2023-24 Budget were estimated to worsen the budget position by $33.4 billion across the forward estimates.22

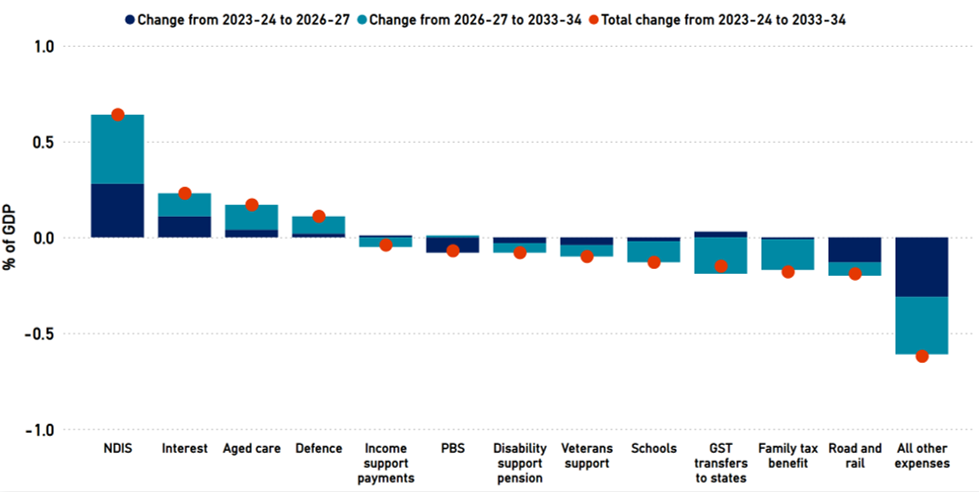

The NDIS continues to be the main driver of growth in expenses as a share of GDP over the medium term, followed by interest payments and aged care. Figure 5-2 shows the programs with the largest movements in expenses as a percentage of GDP across the forward estimates and the medium term.

Figure 5-2: Changes in expenses, 2023-24 to 2033-34

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Table 5-1 shows the expense programs with the largest movements between 2023-24 and 2033-34, as well as the change as a percentage of GDP. Expenditure on GST transfers to the states and territories remains the largest individual expense program, but is expected to decrease as a percentage of GDP across the medium term.

GST revenue as a proportion of GDP is in decline due to a range of factors. Goods and services that are not subject to the GST are making up an increasing proportion of household spending, and there are different trends in the relative prices of items subject to GST compared to items exempt from GST, among other factors. For further information, refer to the PBO’s Budget Explainer, Structural trends in GST. Spending on defence is estimated to increase by almost 72% between 2023-24 and 2033-34 and increase from 2.1 to 2.2% of GDP by 2033-34.

Table 5-1: Comparison of the largest expense programs in the 2023-24 Budget (top 10)

Note: These figures include additional administration expenses and will be slightly higher than figures in the Interactive analysis – net operating balance, revenue and expenses chart and the PBO’s Build your own budget tool.

Note: These figures include additional administration expenses and will be slightly higher than figures in the Interactive analysis – net operating balance, revenue and expenses chart and the PBO’s Build your own budget tool.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

For a full comparison of the largest expense programs, refer to Table B-2 in Appendix B.

The programs presented here are a combination of forward estimates in the 2023-24 Budget and PBO projections. A significant component of the 'total other expenses' category is discretionary government grants, which generally only includes known government grants and does not include a future provision.23 Accordingly, the size of grants accounted for in the budget will usually reduce in size for later years. For example, estimates for capital transfers, a category of grant, reduce from $23.4 billion in 2023-24 to $18.9 billion in 2026-27, a decline of nearly 20%.

This means that, while the budget is consistent with announced government policy, future policy decisions may lead to an increase in expenses for later years of the forward estimates. In total, the 2023-24 Budget estimates government grants to fall 0.6% of GDP between 2023-24 and 2026 27.

The NDIS is projected to be the fastest growing major payment item, eclipsing public debt interest costs. However, projected growth in NDIS expenditure was revised down in the 2023-24 Budget, reflecting the agreement of National Cabinet to the NDIS Financial Sustainability Framework. The framework aims to moderate growth in the NDIS total scheme expenditure to no more than 8% per year by 1 July 2026.

Funding for the NDIS is provided jointly by the Commonwealth and the states and territories, through a series of bilateral agreements.24 Under the existing agreements, annual growth in contributions from the states and territories is fixed at 4%. Consequently, the growth rate of Commonwealth contributions in the 2023-24 Budget is projected to average 10.4% over the 2023-24 to 2033 34 projections period, down from the average 13.8% in the 2022-23 October Budget (2022-23 to 2032 33).25

As a result of the cap on growth in contributions from the states and territories, the Commonwealth is exposed to the risk of scheme cost growth above that cap. Fiscal pressures on the NDIS can arise from increases in the number of people entering the scheme, average payments and inflation. These factors influence growth in costs and so, as a demand-driven program, achieving a target expense growth rate may necessitate government interventions that alter the trajectories of these factors.

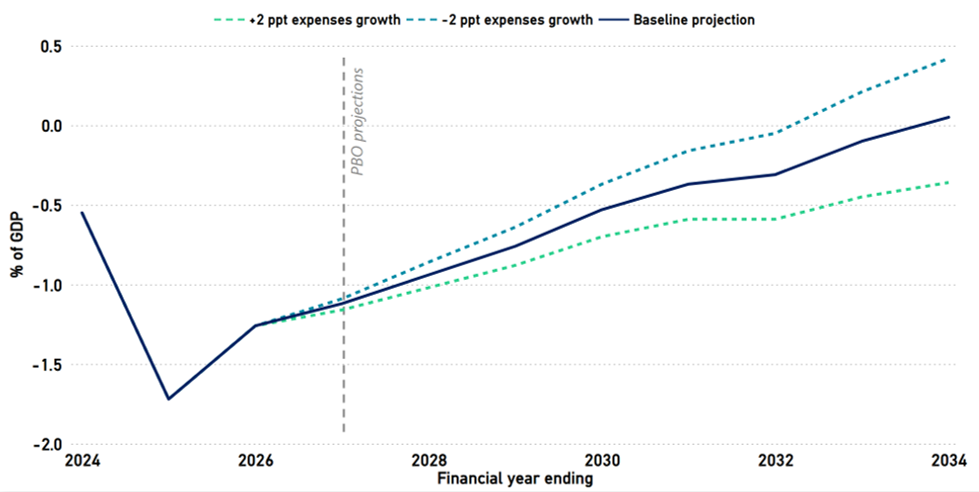

To illustrate the potential impact of this risk, Figure 5-3 below provides a comparison of the fiscal balance under different NDIS expenditure growth scenarios:

- Higher growth: growth in NDIS total scheme expenditure from 2026-27 onwards is 10% per annum, 2 percentage points higher than the baseline.

- Baseline projection: growth in NDIS total scheme expenditure moderates to 8% by 1 July 2026 and remains at this level across the medium term.

- Lower growth: growth in NDIS total scheme expenditure moderates further to 6% by 1 July 2026 and remains at this level across the medium term, 2 percentage points lower than the baseline.

Figure 5-3: Fiscal balance under different NDIS expenditure growth scenarios, 2023-24 to 2033-34

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Figure 5-3 shows the degree to which the fiscal position is sensitive to the growth rate of NDIS costs. If the growth rate in total NDIS costs were 2 percentage points higher by 2033-34 this would mean more than $14 billion per annum in additional expenses, leading to a fiscal deficit, all other things being equal. Conversely, the lower growth scenario would lead to a stronger fiscal surplus by the end of the medium term.

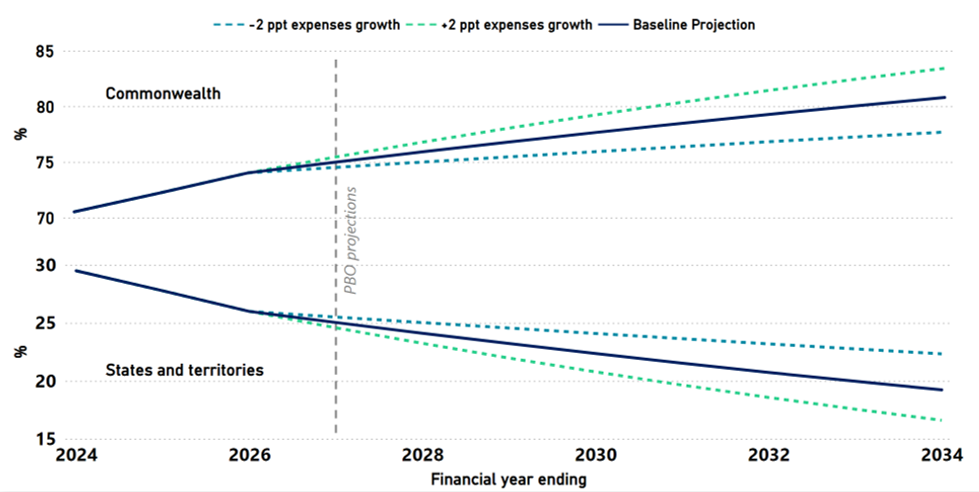

The share of NDIS costs borne by the Commonwealth under the agreements with the states and territories is also highly sensitive to the growth rate in total scheme costs. Figure 5-4 compares the projected proportion of total participant expenses borne by the Commonwealth under each of the scenarios outlined for the period 2023-24 to 2033-34.

Figure 5-4: Commonwealth proportional NDIS contributions under different growth scenarios, 2023-24 to 2033-34

Source: NDIS 2021-22 Annual Financial Sustainability Report, 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: NDIS 2021-22 Annual Financial Sustainability Report, 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Aged care expenditure is also projected to increase as a percentage of GDP across the medium term, driven by the ageing population and policy measures.

Expenditure in this area tends to increase over time because the population is ageing – that is, the number of older people is increasing faster than the number of younger people. Not only does this affect revenue, but it also affects expenses due to increased demand for government-provided aged care services, as well as the age pension and healthcare.

The government has also announced additional expenditure for structural reforms to the aged care system. The 2023-24 Budget allocated $827 million over 5 years to continue to improve the delivery of aged care services and respond to the Final Report of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, under the Improving Aged Care Support measure. This was in addition to the $2.5 billion announced in the 2022-23 October Budget under the Fixing the Aged Care Crisis measure. The 2023-24 Budget also allocated $11.3 billion over 4 years from 2023–24 to fund the outcome of a Fair Work Commission decision to provide an interim increase of 15% to modern award minimum wages for many aged care workers from 1 July 2023.26

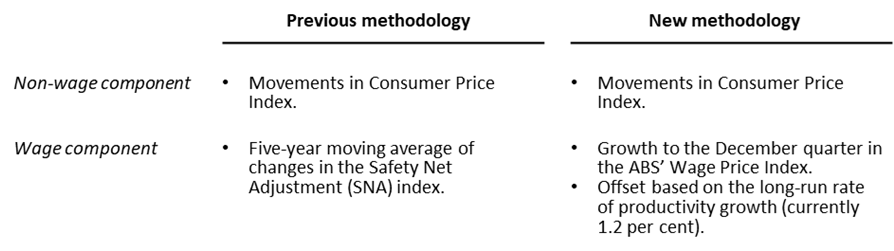

The 2023-24 Budget adopted a new methodology for Wage Cost Indices (WCIs) to better reflect changes in economic conditions. WCIs are used to index agency operating expenses and some administered programs, such as items in the Medicare Benefits Schedule, funding for the Employment Assistance Fund, and funding for the Community Broadcasting Program. The WCIs are also used to index national partnership payments including the National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development and the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. The change in WCI calculation methodology is summarised in Table 5-2 below.

All indexation changes have a compounding impact on payments. The increase is projected to be around $4 billion over the 4 years from 2023-24 to 2026-27 compared to the 2022-23 October Budget.27 Due to the compounding effect of indexation over time, payments made using the new WCI calculation methodologies will grow faster than previously.

Table 5-2: Wage Cost Indices calculation methodology

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2022-23 October Budget, 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

For further information about indexation and the ways in which it affects the budget in the short and long term, refer to our Budget Explainer, Indexation & the budget – long-term impacts.

Appendices

Interactive analysis – net operating balance, revenue and expenses

Note: The default view presents the net operating balance (revenue less expenses) from 2021-22 to 2033-34, calculated using PBO's Build your own budget tool.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

This appendix outlines the economic context for our Beyond the budget 2023-24 and the underlying methodology.

The PBO's projections in this report are based on the policy settings, economic parameters, and budget outcomes of the most recent Australian Government budget. Projections are consistent with the 2023-24 Budget over the forward estimates period (2023-24 to 2026-27) and are used as the base for our projections over the medium-term (2027-28 to 2033-34). The PBO’s medium-term projections are developed independently but are broadly consistent with the medium-term budget position presented in the 2023-24 Budget. The PBO's projection for the UCB in 2033-34 is not significantly different to that presented in the budget, with the PBO's lower projected payments offset by similarly lower projected receipts.

Projections for revenue are generally prepared using a 'base-plus-growth' methodology. Economic parameters are used to estimate growth rates, which are then applied to the relevant base. Projections for expenses are prepared by multiplying the number of expected recipients by the average expense and consider a range of factors. These include population growth, the age structure of the population, estimates of trends in the demand for government services, and program indexation arrangements.

Major fiscal aggregates are presented on both an accrual and cash basis and prepared through a balance sheet framework that uses accounting identities, consistent with our previous reports. Detailed revenue and expense projections are on an accrual basis.

For further information on our balance sheet framework, see the technical appendix to our Beyond the budget 2021-22 report.

Forecasts and projections of economic parameters underpin our analysis. The key economic parameter forecasts are summarised in Budget Paper No.1 of the 2023-24 Budget (Table 1.1).

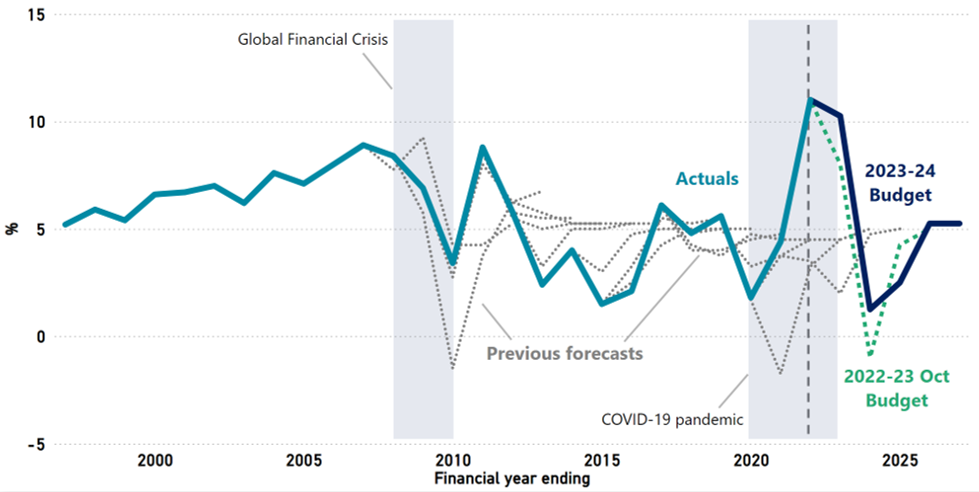

The key changes in the economic outlook presented in the 2023-24 Budget compared to the 2022-23 October Budget (the starting point for our Beyond the budget 2022-23 report) are:

- Economic growth (nominal GDP) is forecast to be higher in 2023-24 but then lower in 2024-25 (shown in Figure A-1 below).

- Employment growth is forecast to be higher in 2023-24, but then broadly consistent in 2024-25.

- the unemployment rate is forecast to be lower in 2023-24 but then broadly consistent in 2024 25.

Figure A-1: Nominal GDP growth, 1996-97 to 2026-27

Note: All values prior to and including 2021-22 are outcomes.

Note: All values prior to and including 2021-22 are outcomes.

Source: 2023-24 Budget, previous budgets, and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

Estimates of fiscal aggregates in the forward estimates period provide the starting point for our fiscal projections across the medium and long-term periods. Estimates of key fiscal aggregates across the forward estimates are also summarised in Budget Paper No.1 of the 2023-24 Budget (Table 1.2).

Source: As presented in Budget Paper No.1, 2023-24 Budget, page 7.

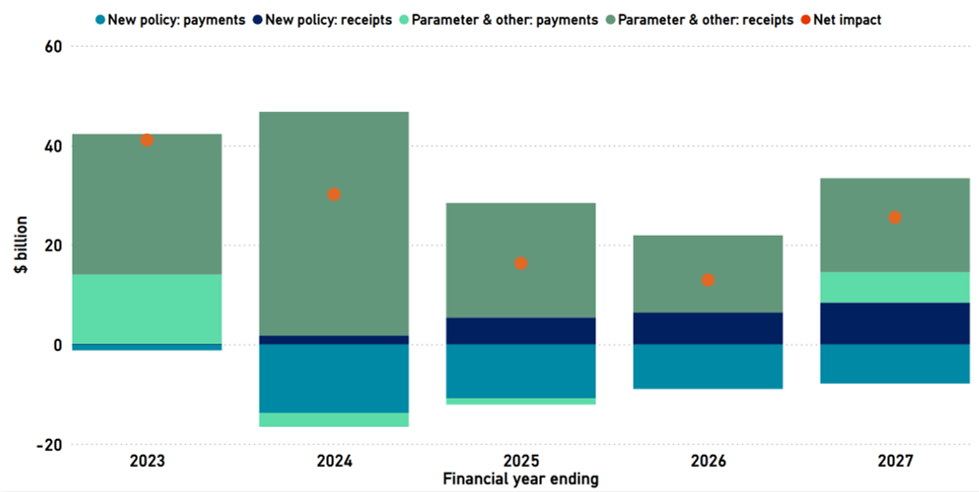

Changes in the budget aggregates between budgets reflect the impact of the prior year actuals as a starting point, parameter variations and policy decisions.

The final budget outcome for 2022-23 is expected to be significantly better than was forecast in the 2022-23 October Budget. This has improved the starting point for the budget aggregate estimates, especially the debt path.

Economic parameter variations contributed the most to the change between budgets, compared to new policy decisions (see Figure A-2).

Figure A-2: Change in underlying cash balance since the 2022-23 October Budget

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Click here for interactive charts.

The key risks to the economic outlook, as articulated in the 2023-24 Budget, are on the downside, with uncertainty around global economic conditions flowing through to Australia. Key risks relate to the impacts of geopolitical instability, as well as higher than anticipated inflation and interest rates. More detail on the economic outlook and the risks are in Budget Statement 2: Economic Outlook.

Medium-term fiscal strategy

The government’s fiscal strategy, as outlined in the budget, has a direct effect on our medium-term projections and fiscal-sustainability analysis.

The 2023-24 Budget fiscal strategy was broadly consistent with the 2022-23 October Budget, to 'improve the budget position in a measured way, consistent with the overarching goal of reducing gross debt as share of the economy over time', underpinned by 'allowing tax receipts and income support to respond in line with changes in the economy and directing the majority of improvements in tax receipts to budget repair' and 'Limiting growth in spending until gross debt as a share of GDP is on a downwards trajectory, while growth prospects are sound and unemployment is low.'28

Bridging the balances

The net operating balance, fiscal balance, headline cash balance, and primary cash balance are common aggregates used in conjunction with the underlying cash balance to examine the budget position.

- The net operating balance (NOB) is equal to the government’s revenue minus its expenses, excluding expenses related to revaluations (such as the write-down of assets). The NOB is an accrual measure, recognising income when it is earned and expenses when they are incurred, even though the associated cash transactions may occur in different financial years.

- The fiscal balance (FB) is also an accrual measure and builds on the NOB. It is equal to the net operating balance less the government’s investments in non-financial assets (such as military equipment) at the time they are acquired or sold. The FB performs a similar function to the underlying cash balance, but on an accrual basis.

- The underlying cash balance (UCB) is the difference between the government’s receipts and its payments. The UCB is a cash measure, which means it records income when it is received and payments when they are made, even though those amounts might have been earned or incurred in a different financial year. Generally, when the government or the media say that the budget is in a deficit or a surplus, they are referring to the UCB.

- The headline cash balance is similar to the UCB, but it also accounts for the government’s investment in financial assets for policy purposes (such as student loans and equity injections). Policies affecting the headline cash balance can have an impact on debt even if they do not affect the underlying cash balance.

- The primary cash balance adjusts the UCB to exclude net interest payments. As governments have little control over interest payments in the short term (interest payments are largely determined by the size of previous budget deficits), it can be useful to view this as a budget balance that is largely within the government’s control.

For further information, see our Online budget glossary.

Table B-1: Comparison of revenue programs

Note: 'Change' refers to the total change between 2023-24 and 2033-34. Numbers may not sum due to rounding. Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

Table B-2: Comparison of expenses programs

Note: 'Change' refers to the total change between 2023-24 to 2033-34. Defence expenditure from 2026-27 is based on the growth in long-term funding commitments made in the 2020 Defence Strategic Update. The base is expenditure for Defence in the most recent Portfolio Budget Statements. For 2031-32, 2032-33, and 2033-34, the PBO has assumed growth in defence spending would be maintained at 5.5%, consistent with the 2023 Defence Strategic Review. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Source: 2023-24 Budget and PBO analysis.

For more explanation of these and other terms, see our Online budget glossary.

Accrual accounting

Accrual accounting records income when it is earned, and records costs when they are incurred, regardless of when the related cash is received or paid. Under accrual accounting, government income is called 'revenue' and costs are generally called 'expenses'. As an example, under accrual accounting, goods and services tax revenue is recorded in the financial year that the goods and services are purchased, even though the government may not receive the related tax amounts until the following financial year.

Cash accounting

Cash accounting records income when cash is received, and records costs when cash is paid out, regardless of when those amounts are earned or incurred. For example, under cash accounting, goods and services tax receipts are recorded in the financial year they are received, even though those tax amounts may relate to goods and services purchased in the previous financial year. Under cash accounting, government income is called 'receipts' and costs are called 'payments'.

Expenses

Expenses in the budget context refers to the cost of providing government services, excluding costs related to revaluations such as the write down of assets. Examples include spending on programs such as the age pension or Medicare, funding provided to the states and territories for public hospitals, or the wages paid to Australian Government employees.

Fiscal balance

The fiscal balance is an accrual accounting measure of the budget balance equal to the government's revenue (for example from taxes) minus its expenses (from providing services such as Medicare and income support such as the age pension), adjusted for government capital investments such as military equipment (known as 'net capital investment in non-financial assets') when they are acquired or sold.

Fiscal sustainability

The government's ability to maintain its long-term fiscal policy arrangements indefinitely, without the need for major remedial policy action. A fiscally sustainable position is one which can be maintained while pursuing similar borrowing and repayment approaches over the long term, such that taxation and spending can be expected to operate within reasonable and expected bounds.

Gross debt

In the budget papers, gross debt is the sum of interest-bearing liabilities, consisting of Australian Government Securities on issue, based on their value when the securities were issued (their 'face value'). Gross debt does not include any of the government’s financial assets that partly offset that debt, or any smaller debts that are not Australian Government Securities.

Headline cash balance

The headline cash balance (HCB) is a cash measure of the budget balance equal to the government's receipts (for example from tax collections) minus payments for operations and investment activities (including certain investments in financial assets). If receipts are lower than payments, the headline cash balance is in deficit, meaning the government does not have sufficient cash to cover its activities and must borrow from financial markets.

Net debt

Net debt is the sum of selected financial liabilities (deposits held, advances received, government securities, loans, and other borrowings) less the sum of selected financial assets (cash and deposits, advances paid, and investments, loans, and placements). It is a common measure of the strength of a government's financial position. In the net debt calculation, Australian Government Securities are valued as the price they are currently trading at (their 'market value') rather than their value when the securities were issued (their 'face value').

Net financial worth

Net financial worth measures the total financial assets (such as cash or shares in a company) held by a person or organisation at a fixed point in time, minus the value of any liabilities, such as outstanding debts. Net financial worth is a broader measure of the government's financial position than net debt, but it is narrower than net worth.

Net worth

Net worth measures the government's overall wealth, calculated as total assets (both financial and non-financial) less total liabilities. Net worth is the broadest measure of the government’s financial position.

Payments

Payments capture all outgoing cash transactions from the Australian Government to individuals, organisations, or other levels of government. In the budget context, payments are those that affect the underlying cash balance and comprise cash transactions for operating activities and the purchase of non-financial assets. Examples include an age pension payment, a Medicare rebate for a doctor's visit, and the wages of a Centrelink employee.

Interest payments

Interest payments are the cash payments on the government’s debt liabilities which are recorded as a cost to government in the budget. Net interest payments are equal to interest payments minus the cash interest receipts earned by the government on investments in interest-bearing financial assets.

Primary cash balance

The primary cash balance adjusts the underlying cash balance to exclude interest payments on debt as well as interest receipts. As governments have little control over interest payments in the short term (interest payments are largely determined by the size of previous budget deficits), it can be useful to view this as a budget balance that is largely within the government’s control.

Receipts

Receipts are the government's income, recorded at the time they are received as reported on a cash accounting basis. In the budget context, receipts are those that affect the underlying cash balance, so exclude the repayment of loans and other cash flows relating to the exchange of financial assets. Most government receipts are tax receipts, such as company tax, personal income tax, and goods and services tax. The government also receives non-tax receipts, such as interest earned on government loans and dividends from government investments.

Revenue

Revenue is government income, recorded at the time it is earned and reported on an accrual accounting basis. Most government income is made up of tax revenue, such as company tax, personal income tax, and goods and services tax. The government also receives non‑tax revenue, such as interest earned on government loans and dividends from government investments.

Underlying cash balance

The underlying cash balance (UCB) is a cash measure of the budget balance equal to the difference between the government's receipts and its payments. It is one of several indicators known as 'budget aggregates' that measure the impact of the government's budget on the economy. When the government or the media say the budget is in surplus or deficit, they are generally referring to the underlying cash balance, or sometimes the net operating balance or fiscal balance. More specifically, the underlying cash balance is equal to the government's receipts (for example from tax collections) minus its payments from providing services (such as Medicare) and support (such as the age pension). The types of receipts and payments used in the calculation include those from buying and selling non‑financial assets, such as buildings or equipment. The term 'underlying' is used because it excludes some cash transactions that are captured in the broader, but less commonly used, headline cash balance.

- The 2023-24 Budget assumes that the iron ore spot price declines from a March quarter 2023 average of US$117 to US$60/tonne; the metallurgical coal spot price declines from US$342 to US$140/tonne; the thermal coal spot price declines from US$260 to US$70/tonne; and the LNG spot price declines from US$16 to US$10/mmBtu.

- Reserve Bank of Australia (n.d.) Cash Rate Target, RBA website, accessed 8 June 2023. Increases in the overnight cash rate since May 2023 are not factored into the 2023-24 Budget baseline.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 251, Australian Government.

- Interest may be thought of as a payment related to accumulated past budget balances, meaning that the primary balance may be thought of as a more appropriate measure of the government’s current fiscal stance.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 108, Australian Government.

- Our middle case for nominal GDP growth incorporates the 2023-24 Budget assumption for long-run productivity growth of 1.2%.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) Population Projections, Australia, ABS website, accessed 8 June 2023.

- Our cases assume each of the 3 variables that determine the debt-to-GDP ratio across the long term converge to our assumed values after 2033-34.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 99, Australian Government.

- The Henry tax review (Australia's Future Tax System Review Final Report | Treasury.gov.au) identified five principles of good tax design: equity, efficiency, simplicity, sustainability and policy consistency.

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Advancing Prosperity, Australian Government

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 119, Australian Government.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 99, Australian Government.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 186, Australian Government.

- Grattan Institute (2020) No free lunch: higher super means lower wages, page 3, Grattan Institute.

- The aggregate average marginal tax rate is calculated as the average tax that would be paid on an additional $1 of income for the entire taxpayer population, weighted by taxable income.

- Australian Government (2015) Re:think Tax discussion paper, page 23, Australian Government.

- Australian Government (2021) 2021 Intergenerational Report, page 136, Australian Government.

- Parliamentary Budget Office (2021), Bracket creep and its fiscal impact, Figure 9.

- See Figure 4-3.

- PBO estimate from Build your own budget.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No 1, page 198, Australian Government.

- Other factors that contribute to the decline in 'total other expenses' from 2023-24 to 2033-34 include: unfunded superannuation expenses decreasing as unfunded superannuants retire; the funding for overseas development assistance and other smaller programs such as the Commonwealth Grants Scheme are indexed with a growth rate lower than nominal GDP; and a number of payments to individuals growing more slowly than nominal GDP as they are projected on the basis of CPI and population growth.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme (2022) Intergovernmental agreements, NDIS website, accessed 1 June 2023.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 98, Australian Government.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 105, Australian Government.

- Australian Government (2023) 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No.1, page 104, Australian Government.

- Extract from the Government’s Economic and Fiscal Strategy, Budget Paper No.1, 2023-24 Budget, page 87

Build your own budget

The modelling in Build your own budget underpins the projections and analysis contained in Beyond the budget, and users can replicate the scenario analysis contained in Beyond the budget for a more comprehensive view of overall impacts.

Online budget glossary

Explaining key terms related to the Commonwealth Government budget in a non-technical way.