Terms in the glossary include those used in the Commonwealth budget papers as well as some related terms that are important for understanding the budget in the context of the broader economy. The glossary complements the PBO guide to the budget.

We welcome suggestions for additional terms to be included in future updates of the glossary. If you find this glossary useful or have suggestions for improvement or additional terms, please email your feedback to feedback@pbo.gov.au.

All links in the glossary are current as at 22 December 2021.

A-B

Accrual accounting records income when it is earned, and records costs when they are incurred, regardless of when the related cash is received or paid. Under accrual accounting, government income is called 'revenue' and costs are generally called 'expenses'. As an example, under accrual accounting, goods and services tax revenue is recorded in the financial year that the goods and services are purchased, even though the government may not receive the related tax amounts until the following financial year.

Accrual accounting differs from cash accounting, which records income when cash is received, and records costs when cash is paid out, regardless of when those amounts are incurred. Under cash accounting, government income is called 'receipts' and costs are called 'payments'.

The Commonwealth Budget presents both accrual and cash indicators. Budget Paper No. 2, which details new government spending and tax measures, was presented in accrual terms (showing the impact of new measures on the fiscal balance) prior to the 2020-21 Budget. However, the 2020‑21 Budget presented budget measures on a cash basis, and it is now convention for Budget Paper No. 2 to be presented in cash terms (showing the impact of new measures on the underlying cash balance).

Accrual accounting and cash accounting can give different estimates for budget aggregates because the timing between earning revenue or incurring expenses might differ from when the related cash transition occurs.

For many items, accrual and cash estimates are similar, but in some cases they are very different. For example, most Medicare rebates are paid electronically immediately after a doctor's visit, so the accrual and cash estimates of the costs are very similar. In contrast, the accrual and cash costs of some of the Commonwealth Government's superannuation schemes are very different. The government accrues the obligation to pay eligible individuals' superannuation benefits during their employment, which is reflected as increased liabilities under accrual accounting. The government does not, however, actually make any payments until the individual retires, so the cash costs are zero until then. This means there is a large difference between the accrual and cash estimates of these superannuation costs.

Appendix A of the PBO's report no. 01/2020 Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees contains more details on which budget aggregates are in accrual or cash terms.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget aggregates, budget paper, cash accounting, expense, fiscal balance, financial year, measure, payment, receipt, revenue, underlying cash balance

Administered funding is spending that is managed by government agencies but that they do not directly control. Administered funds include programs governed by eligibility rules and conditions that are set out in legislation, such as income and family support payments, and grant programs that are managed by agencies. In contrast, departmental funding is managed and controlled directly by departments and agencies. Typically, these funds are used for the purpose of day‑to‑day operations and program‑support activities.

For example, government assistance for the costs of child care as set out in the A New Tax System (Family Assistance) (Administration) Act 1999 is an administered expense, and the costs associated with making the assistance payments, such as paying Services Australia staff to assess assistance claims, is a departmental expense.

Administered expenses are a much larger component of total expenses than departmental expenses, accounting for around 86 per cent of total expenses in 2019-20. Details of administered funding across all Commonwealth Government agencies are published in the budget in Budget Paper No. 4: Agency Resourcing. Commonwealth Government agencies also report their administered items in greater detail in their Portfolio Budget Statements (budget information for a Government Minister’s area of responsibility) and in annual reports.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget paper, departmental, expense, Portfolio Budget Statement, program

Alternative financing refers to when governments fund policies or projects using alternatives to the typical approach of paying for them directly with cash (sometimes known as 'direct funding'). Alternative financing often involves the government providing money to another entity, like a company or individual, in exchange for a financial return in the future. In contrast, under direct funding, the funds are not expected to be repaid. Examples of alternative financing include loans and examples of direct funding include income support payments like the age pension.

Alternative financing arrangements can include:

- purchasing an equity stake in a company (known as an 'equity injection') — for example the Commonwealth Government's 100 per cent ownership stake in NBN Co Limited.

- making loans, such as concessional loans, which are offered at more favourable conditions than those the borrower could obtain from a bank or other commercial lender. Examples include the government's drought loans, Higher Education Loan Program (HELP), or infrastructure loans.

- providing a guarantee that the government will assume responsibility for payment where an eligible party defaults — for example the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme. In these cases, the expectation of a financial return may not apply.

In recent years, successive governments have been making greater use of alternative financing. There can be sound policy reasons for using alternative financing arrangements to fund particular government policies. Many of the costs associated with alternative financing, such as a change in the value of financial assets, are not fully captured in some commonly used indicators of the budget position such as the underlying cash balance (collectively known as 'budget aggregates').

Due to the complexity of alternative financing arrangements, their value and cost can be more uncertain than those of direct funding. For example:

- the value of an ownership stake can change over time, depending on a valuation of the business

- there is uncertainty around whether and when loans will be repaid

- there is uncertainty around how many parties will default on payments guaranteed by the government.

For further information:

- see the Parliamentary Budget Office’s report no. 01/2020, Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees for an explanation of alternative financing arrangements and their impact on the budget

- see the Department of Finance’s Investment Instruments entry in their Commonwealth Investments Toolkit for an explanation of when the government might use alternative financing.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget aggregates, concessional loan, equity, grant, payment

Automatic stabilisers are parts of government policy that adjust automatically to work against changes in economic conditions such as recessions. Two commonly cited examples are unemployment benefits and taxation revenues.

In an economic downturn or recession:

- more people may become unemployed and the total cost of unemployment benefits, which are paid to all eligible recipients, will be higher as a result

- personal and company incomes will likely be lower, and income taxes, which are charged as a share of income, will automatically be lower as a result.

Both the higher unemployment benefits and lower taxes happen automatically without the government changing its existing policies. By putting more money into the economy and taking less out, this helps to support households and businesses during an economic downturn or recession. If the economy is booming, automatic stabilisers work in reverse and can help prevent the economy from 'overheating'. For this reason, the policies are said to work 'counter cyclically' (that is, against the economic cycle).

Automatic stabilisers can be contrasted with 'discretionary' fiscal policy, which is any policy requiring a new decision by the government. For example, during the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-09, increased expenditure by the government on unemployment benefits (due to an increased number of recipients) was an automatic stabiliser, while one-off payments to low and middle-income individuals and households with dependent children, were part of a fiscal stimulus package of discretionary measures.

The effectiveness of taxes and benefits as automatic stabilisers will be affected by the administrative arrangements for collection or payment. For instance, corporate taxes are collected as instalments, with the instalment rate based on past income. In an economic downturn, instalment rates may not adjust quickly, with the reduction in tax only realised when company tax returns are lodged after the end of the year.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: demand-driven program, fiscal policy, fiscal stimulus, measure, recession

Bracket creep describes a situation where income growth causes individuals to pay a higher share of their income in tax, even though there may not have been changes to tax rates or thresholds. Bracket creep is usually associated with rising wages, such as in an inflationary environment.

Bracket creep is one result of Australia’s progressive personal income tax system, which involves a series of tax ‘brackets’ with tax rates that increase with income. This system ensures higher income earners pay a greater share of their income in tax compared to individuals earning lower incomes.

Because tax brackets in Australia are not indexed to income growth, individuals whose income increases over time will see a greater share of their income subject to higher tax rates, even if their income has simply risen in line with inflation. This impact occurs regardless of whether income growth pushes their income into the next tax bracket. Figure 1 demonstrates how an individual’s marginal and average tax rates increase with taxable income.

Source: PBO Budget Explainer: Bracket creep and its fiscal impact

For example, consider an individual with an annual income of $80,000. Their marginal tax rate is 32.5% and they pay around $16,500 in tax, which is an average tax rate of 20.6%. If this individual’s income were to increase by 6% to $85,000, they would now pay around $18,100 in tax, an increase of almost 10%, to an average tax rate of 21.3%, even though they remain in the same marginal tax bracket.

Bracket creep has a positive impact on the budget because it typically means that tax revenues grow as a proportion of the economy over time without the need for governments to explicitly increase taxes. Governments can choose to adjust tax rates or thresholds to reduce the impact of bracket creep – this is sometimes referred to as ‘returning’ bracket creep.

For further information see the PBO’s budget explainer no 1/2021 Bracket creep and its fiscal impact.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: Indexation, inflation, marginal tax rate, tax revenue

The budget is the Commonwealth Government’s main annual financial report that outlines the economic and fiscal outlook for Australia. It is comprised of a series of documents, including the budget papers, the budget speech, the budget overview, and information on each government Minister's area of responsibility (their 'portfolio'). The budget provides an estimate of money coming in (revenue), money going out (expenses), and how much is owed (net debt). The budget is also a policy statement on the government’s priority areas of focus and how they intend to meet their objectives.

The budget is the first of three main annual budget reporting documents required by the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 (the Charter).

- The budget sets out the economic and fiscal outlook, and the government's fiscal strategy.

- The Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook provides updated information on the government’s fiscal performance, which can be assessed against the fiscal strategy set out in the budget.

- The Final Budget Outcome provides the final fiscal outcomes for the year.

The Charter does not mandate a timeframe for the release of the budget, however it typically occurs on the second Tuesday in May and is accompanied by a budget speech. The budget is tabled in the House of Representatives by the Treasurer, along with the Appropriation Bills which allow for the spending of public funds.

Although the Treasury and Department of Finance work to prepare the budget papers, they are the government’s documents and are signed off by the Treasurer and the Finance Minister.

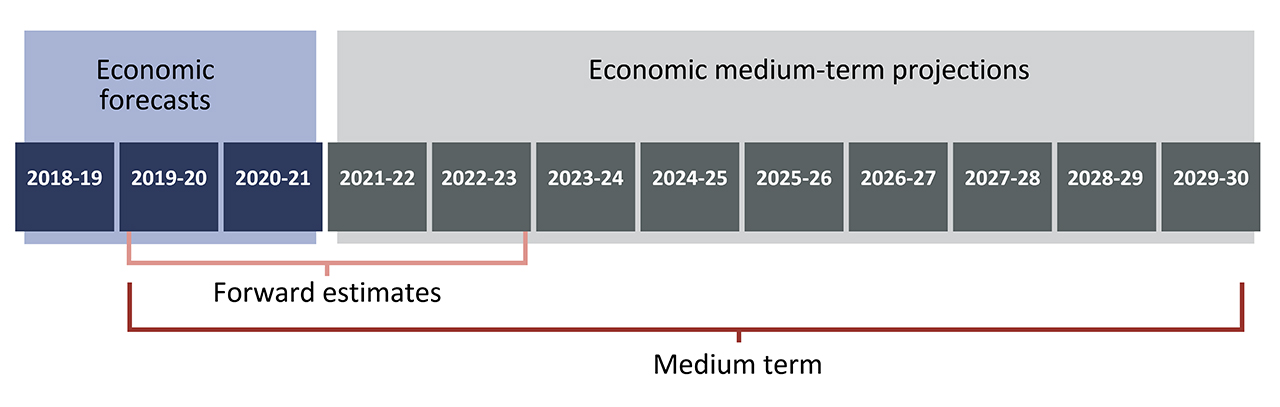

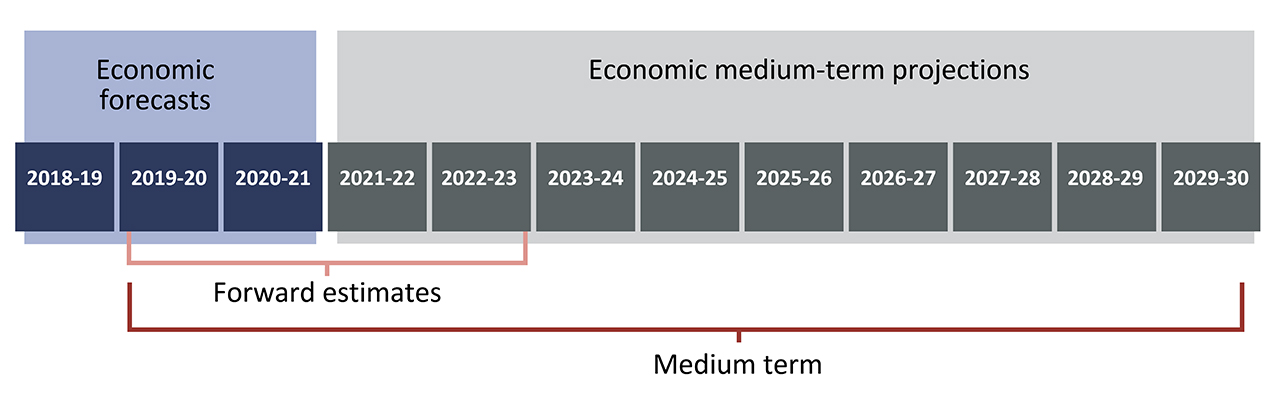

The budget includes expenses and revenue estimates for the current financial year, the budget year, and the following three financial years (known as the forward estimates period). Estimates are published at the general government sector level through budget papers, and at the portfolio level through Portfolio Budget Statements. All budget documents and related material can be found on the budget website.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget paper, Charter of Budget Honesty, net debt, expense, Final Budget Outcome, financial year, forward estimates, general government sector, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Portfolio Budget Statement, revenue

Budget aggregates are summary indicators that provide information on the government's financial position. Some widely cited budget aggregates are the underlying cash balance, the net operating balance, the fiscal balance, and net debt. A single budget aggregate can only present a partial picture but combined they provide a good summary of the government's financial situation and its impact on the broader economy. 'Aggregate' refers to the fact that these indicators look at total impacts, such as total government cash flows.

Four of the main budget aggregates (fiscal balance, net operating balance, underlying cash balance and headline cash balance) show whether the budget is in surplus or deficit, while three (net worth, net financial worth and net debt) provide information about the government's assets and liabilities.

If the government or media say that the budget is in surplus or deficit, they are generally referring to the underlying cash balance, but sometimes to the net operating balance or fiscal balance. If the budget is in surplus, all income received by the government (for example through income taxes) is larger than all the spending by the government (for services such as Medicare rebates, and social welfare payments such as the age pension). The particular calculations depend on the particular budget aggregate, including whether it records transactions when economic events occur (known as accrual accounting), or when money is actually paid or received (known as cash accounting).

Indicators that show the budget surplus or deficit are important, but they do not provide information about the government's assets. Information about the government's assets is provided by indicators such as net worth, net financial worth and net debt.

Public accounting standards and agreements between Commonwealth and state Treasurers set out a minimum set of budget aggregates that are updated at every budget, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Final Budget Outcome, and (in the lead-up to a general election) the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook. Budget aggregates are found in several places in the budget papers.

- Statement 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook of Budget Paper No. 1 gives projections for the budget aggregates that show whether the budget is in surplus or deficit.

- Statement 7: Debt Statement of Budget Paper No. 1 provides projections of net debt.

- Statement 10: Australian Government Budget Financial Statements of Budget Paper No. 1 provides complete projections of the budget aggregates.

For further information:

- see Appendix A of the Parliamentary Budget Office's report no. 01/2020 Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees for an explanation of budget aggregates

- on technical detail on budget aggregates, see the Department of Finance's Major fiscal aggregates and the Australian Bureau of Statistics' Government Finance Statistics manual.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: accrual accounting, budget, budget paper, cash accounting, Final Budget Outcome, fiscal balance, headline cash balance, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, net, net debt, net financial worth, net operating balance, payment, Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook, underlying cash balance

The budget papers are four key documents produced as part of every budget that outline the economic and fiscal outlook of the Commonwealth Government. Together, they provide a large amount of information about the government's current and projected financial position (including revenue, expenses and the level of net debt), details of the government's fiscal strategy, new government decisions, and funding provided to the states and territories.

In preparing the budget papers, all government decisions and other circumstances that have an effect on revenue and expenses must be taken into account. The four budget papers are described below, with specific references to the sections in the relevant 2021-22 Budget Papers.

Budget Paper No. 1: Budget Strategy and Outlook contains a set of chapters known as 'statements' that provide high-level information about the overall economic outlook and the government's fiscal position. It contains forecasts of key economic parameters (such as gross domestic product (GDP) growth, unemployment and the consumer price index), the government's fiscal strategy and outlook, estimates of government revenue, expenses and net capital investment, and the level of government net debt. It also presents detailed financial statements and historical budget statistics.

Budget Paper No. 2: Budget Measures outlines new decisions the government has taken. It contains details of every new decision, or 'measure', announced since the preceding Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, including a description and the financial impact over the current financial year, the budget year and the following three financial years (the forward estimates). Measures are grouped according to the component of the Commonwealth Government's finances they primarily affect – revenue (Part 1), expense (Part 2) or capital (Part 3).

Budget Paper No. 3: Federal Financial Relations contains information on payments made by the Commonwealth to the states and territories. These payments fall into two categories: payments for specific purposes (Part 2) and general revenue assistance (Part 3).

- Payments for specific purposes are funds provided on the condition that the states and territories spend the money as directed, such as to fund schools and public hospitals.

- General revenue assistance refers to funds provided to the states and territories without any conditions attached, for example revenue from the goods and services tax.

Budget Paper No. 4: Agency Resourcing contains information on funding for each government agency. This includes the type of legislative authority that allows a government agency to spend public funds (the appropriation type) and the amount of money that it is allowed to spend (Part 1). It also details the expected level of staffing for each government agency (Part 2).

For further information:

- the Parliamentary Library’s Quick Guide to the Commonwealth Budget describes the aim and contents of each budget paper

- the current budget papers can be found on the Budget website.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, capital, consumer price index, expense, gross domestic product, measure, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, net debt, parameter, payment, revenue

C

Capital comprises assets, some of which can be used to directly produce goods or services.

Capital includes financial assets such as cash and loans, and non-financial assets such as buildings and machinery. Some economic theories also define other types of capital, for example human capital (such as the stock of knowledge and skills), and natural capital (the stock of natural assets that support life).

Non-financial assets, like land, buildings and machinery, are combined with labour inputs to produce goods and services. For example, a farm uses farm machinery, land and the effort of farm labourers to produce crops. Looking across the economy as a whole, the total value of all of these goods and services is called gross domestic product.

The total value of all capital used for production in the economy at a given point in time is known as the 'capital stock'.

- Increases in the capital stock from acquiring existing assets or creating new assets are referred to as 'investments'.

- The decrease in the value of the capital stock as a result of the production process is referred to as 'depreciation'. For example, suppose a manufacturer invests in a machine worth $100,000. At the end of the next year, the machine is valued at $90,000, reflecting its use at the factory. The $10,000 decrease in the value of the machine is depreciation due to wear, accidental damage or becoming gradually obsolete.

In a Commonwealth Government budget context, capital generally refers to non-financial assets. As such, net capital investment is defined as the net sale and investment in non-financial assets less depreciation expenses. See the net capital investment entry for further detail, including where information on the government's investment can be found in the budget papers.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: gross domestic product, net, net capital investment, non-financial asset

Capped funding is where the government provides a fixed sum of money for a program. This means that the maximum amount of government spending on the program will not change, even if, for example, there are changes in the demand for the program or costs are higher than expected.

Capped funding can be distinguished from uncapped or demand‑driven funding, which does not have any fixed limits on spending. For example, a commitment that the government will provide $500 million for the construction of a road from A to B is a capped funding commitment, while the government will fund construction of a road from A to B is uncapped because the precise amount is not specified and depends on a range of external factors. Income support payments, such as the JobSeeker payment, are demand‑driven because the total amount of government spending depends on the number of eligible recipients.

One reason governments allocate capped spending is to provide some assistance and support while limiting their expenditure. Unlike demand‑driven programs, where the final expenses can be hard to predict, spending on capped programs is certain and will not change unless the government chooses to amend the amount allocated to the program.

The main risk with capped funding is that the allocated amount of funds may not be enough to achieve the objectives of the program. In this case, additional sources of funding will need to be found by the funding recipient to deliver the program, unless the government chooses to increase the capped amount.

Capped funding can be ongoing (such as a fixed amount provided for a program every year) or terminating (such as a one‑off grant). Capped funding can be a fixed dollar amount or can increase each year in line with inflation.

Capped funding can be allocated in a number of ways, including through one‑off grants, establishing competitive processes or allocating funding on a 'first‑in, first‑served' basis until the cap is reached.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: demand‑driven program, expense, grant, inflation, program, uncapped funding

Cash accounting records income when cash is received, and records costs when cash is paid out, regardless of when those amounts are earned or incurred. For example, under cash accounting, goods and services tax receipts are recorded in the financial year they are received, even though those tax amounts may relate to goods and services purchased in the previous financial year. Under cash accounting, government income is called 'receipts' and costs are called 'payments'.

Cash accounting differs from accrual accounting which records income when it is earned, and records costs when they are incurred, regardless of when the amounts are actually received or paid out. Under accrual accounting, government income is called 'revenue' and costs are generally associated with 'expenses'.

The Commonwealth budget presents cash and accrual indicators. Budget Paper No. 2, which details new government spending and tax measures, was presented in accrual terms (showing the impact of new measures on the fiscal balance) prior to the 2020-21 Budget. However, the 2020‑21 Budget presented budget measures on a cash basis, and it is now convention for Budget Paper No. 2 to be presented in cash terms (showing the effect of new measures on the underlying cash balance).

For many items, cash and accrual estimates are similar, but in some cases they are very different. For example, most Medicare rebates are paid electronically immediately after a doctor's visit, so the cash and accrual estimates of the costs are very similar. In contrast, the cash and accrual costs of some of the Commonwealth's superannuation schemes are very different. The government accrues the obligation to pay eligible individuals' superannuation benefits during their employment, which is reflected as increased liabilities under accrual accounting. The government does not, however, actually make any payments until the individual retires, so the cash costs are zero until then. This means there is a large difference between the cash and accrual estimates of these superannuation costs.

Appendix A of the PBO's report no. 01/2020 Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees contains more details on which budget aggregates are in cash or accrual terms.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: accrual accounting, budget, budget aggregates, budget paper, expense, financial year, fiscal balance, measure, payment, receipt, revenue, underlying cash balance

The Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 (the Charter) is the legal framework for conducting government budget policy in Australia. The Charter aims to improve budget policy outcomes by establishing a set of rules and principles that guide how the government sets and reports on its budget performance.

To facilitate public scrutiny of fiscal policy and performance, the Charter mandates the government to publicly release the following reports:

- a budget that sets out the economic and fiscal outlook, and the government's fiscal strategy

- a Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) that provides updated information on the government's fiscal performance that can be assessed against the fiscal strategy set out in the budget. The MYEFO must be published by the end of January in each year, or within six months after the latest budget

- a Final Budget Outcome that provides the final fiscal outcomes for the year, and must be published within three months of the end of each financial year

- a Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook report if a general election is called

- an Intergenerational Report at least once every five years, which assesses the long-term sustainability of current government policies over the next 40 years.

The Charter outlines the information that should be included in each of these publications and what accounting standards to use when reporting financial information.

Importantly, the Charter sets the objective of the government's fiscal policy, which is to maintain ongoing economic prosperity and the welfare of Australians. It sets out five principles of fiscal management and requires the government to publish fiscal strategies consistent with these principles. The principles include ensuring policy decisions have taken account of the financial effects on future generations, and managing financial risks carefully, including by maintaining government debt at prudent levels.

Fiscal strategy statements are typically found in Statement 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook of Budget Paper No. 1. For example, in the 2021-22 Budget, the government's short-term fiscal strategy was to drive down the unemployment rate to pre-COVID-19 level or below, and ensure the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic was sustained and secure. The government's medium-term fiscal strategy was to stabilise and then reduce debt as a percentage of GDP.

The Charter outlines arrangements under which the Treasury, the Department of Finance and the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) may be requested to cost election commitments during the caretaker period prior to a general election. The caretaker period begins at the time the House of Representatives is dissolved and continues until the election result is clear or, if there is a change of government, until the new government is appointed. During the caretaker period, a party can request a costing from the Department of Finance, the Treasury or the Parliamentary Budget Office, but not from more than one of these.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget paper, debt, Final Budget Outcome, financial year, fiscal policy, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, net financial worth, Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook

In the context of funds allocated to a program, committed funding is money that the government has a contractual or other legal obligation to pay. These funds are usually part of a fixed overall amount of money allocated to a program, known as the capped funding amount. The money remaining after accounting for committed funds is called 'uncommitted' funds. Uncommitted funds may be taken out of a program and used to fund new initiatives without increasing the budget deficit (or reducing the surplus).

For example, if the budget allocated $10 million for a grants program and then entered into contracts for specific grants worth a total of $6 million, that $6 million of funding is committed. The remaining $4 million of funding is uncommitted. At this point, if the government decided not to continue with the grants program, that $4 million could be reallocated to another program without affecting the budget position. The government may not be able to recoup some or all of the $6 million they have already committed.

The distinction between committed and uncommitted funds is usually made when a program is managed by a government agency or other operator on the government's behalf (known as an administered program).

The term 'commitment' can be used in a variety of ways, however this material relates to the relatively narrow concept of contractual or legal obligations.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: administered funding, budget, budget aggregates, capped funding, grant, program

Concessional loans are loans offered by governments so businesses and individuals can borrow money on more favourable terms than they could get from a bank or other commercial lender. These more-favourable terms can include:

- reduced interest rates

- no repayments for several years

- an extended interest-free period.

Concessional loans are used to support policy objectives when private financing is unavailable or unaffordable. For example, the Commonwealth Government's drought loans are offered to help farm business owners prepare for, manage and recover from drought. These loans are concessional as they offer below-market interest rates and the first two years are interest free. The Commonwealth Government's biggest concessional loan program is the Higher Education Loan Program (HELP), which provides loans to students for higher education tuition costs.

Concessional loans can represent a net improvement or deterioration in government finances. This will depend on the amount of:

- revenue generated from the loan — for example from interest payments

- principal repaid — as with all loans, there is a risk that some of the loan will not be repaid in full

- expenses payable by government — most notably public debt interest, which is the cost to the government of borrowing to fund the loans.

Concessional loans are a form of alternative financing and differ to grants in that there is an expectation that loans will be repaid.

The accounting treatment of concessional loans is similar to standard loans but there are additional components to recognise the more-favourable terms of the loan.

For further information:

- see the Parliamentary Budget Office's report no. 01/2020, Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees for an explanation of concessional loans and their impact on the budget

- see the Department of Finance's Q&A – Concessional Loans for answers to commonly asked questions on concessional loans

- see the Department of Finance's Investment Instruments entry in their Commonwealth Investments Toolkit for an explanation of when the government might use concessional or standard loans

- on more technical details and worked accounting calculations, see Appendix A of the Department of Finance's RMG115: Accounting for concessional loans

- see PER062, PER314 and PER649 in the PBO’s 2019 Post-election report of election commitments for examples of election commitment costings that include concessional loan schemes.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: alternative financing, budget, expense, grant, public debt interest, revenue

The conservative bias allowance (CBA) is an aggregate provision in the Australian Government budget to take account of the historical tendency to underestimate expenses over the forward estimates. The purpose of the CBA is to reflect the inherent uncertainty in expense estimates the further into the future the projections are made. The CBA is typically the largest component of the government’s contingency reserve.

Including the CBA in the budget estimates means that the overall budget bottom-line is more realistic over the forward estimates period than it would otherwise have been. The CBA is not a policy reserve and therefore no ‘savings’ can be claimed by adjusting it down.

Because it is an aggregate adjustment, the size of the CBA does not imply underestimation in any specific program, but only for the sum of all relevant programs in total. In calculating the size of the CBA, only program-specific factors are included, such as demographic factors that may impact eligibility for programs.

The CBA does not account for economic parameter variations, such as changes in prices or new policy decisions. For example, the possibility of a change in age pension payment rates due to increases in the consumer price index (an economic parameter variation) or a change in the payment rate for the age pension (a new policy decision) are not taken into account by the CBA.

The amount of the CBA provision is calculated as a certain percentage of total expenses, excluding goods and services tax (GST) payments to the states and territories. Because uncertainty is greater the further into the future a forecast is made, the level of CBA varies for each year of the forward estimates. Amounts for the CBA are presented in budget paper 1. The 2022-23 Budget Paper No. 1 shows the amounts on page 172, for example.

The current CBA provision is set to 0% for the budget year, 0.5% for the following year (the first forward year), 1% for the next year and 2% for the final year. If, for example, total expenses were estimated to be around $600 billion and GST payments to the states and territories around $80 billion, the total amount of CBA provisioned would add $2.6 billion to forecast expenses for the first year of the forward estimates.

For further information on the CBA and its budget treatment see the PBO’s budget explainer no 2/2021 The Contingency Reserve.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, contingency reserve, expenses, forward estimates, parameter, program

The Consolidated Revenue Fund (the Fund) acts like the Commonwealth Government’s bank account, where all of its deposits and withdrawals of money are made.

All money raised or received by the Commonwealth Government automatically forms part of the Fund and all expenditure by the Commonwealth Government also comes out of the Fund. For example:

- revenue from personal income and other taxes, interest earned on government loans, and dividends from government investments are all included in the Fund

- spending on government policies and programs, such as payments of Medicare benefits or the age pension, are made from the Fund. All grants and payments to state and territory governments, such as those for hospitals and schools, also come out of the Fund.

The only exception to the above is money received by Commonwealth entities that are legally separate to the Commonwealth Government (known as 'Corporate Commonwealth entities'), such as Australia Post. In these cases, money received does not automatically form part of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

The Consolidated Revenue Fund was created to ensure Commonwealth Government spending is first reviewed by members of the Parliament. Money can only be drawn from the Consolidated Revenue Fund to pay for Commonwealth Government activities once the Parliament has approved the expenditure by passing an appropriation.

The Consolidated Revenue Fund was established by section 81 of the Australian Constitution.

While it can be helpful to think about the Consolidated Revenue Fund as a bank account, technically this is not the case. The Official Public Account group of accounts, provided by the Reserve Bank of Australia, act as the Commonwealth Government’s actual bank account. This is where most of the operations of the Consolidated Revenue Fund take place.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: expense, grant, payment, program, revenue

The consumer price index (CPI) is one of the most frequently used indicators of inflation, which measures the price changes facing households.

In Australia, the CPI is one of the main indicators used to adjust government payments, like the JobSeeker payment, to reflect the change in prices over time.

Typically, the general level of prices across the economy rises over time, which is called inflation, but prices can also fall (this is called deflation). If prices are rising, $100 in 2025 will not buy as much as $100 in 2020. Another way of saying this is that the same nominal amount of money has lower purchasing power.

To measure inflation, the CPI calculates the percentage change in the price of a fixed collection or 'basket' of goods and services that reflects the spending habits of households. If households spend more of their income on an item, that item will have a larger share or 'weight' in the basket of goods and services, and its price changes will have a bigger influence on the CPI.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) calculates and publishes the CPI every three months.

The CPI is not a cost-of-living index even though both of them measure changes in the prices of goods and services that households buy. The CPI measures the changes in the price of a fixed basket of goods and services, while a cost-of-living index measures changes in the minimum amount a household would need to spend to maintain the same standard of living. The ABS also publishes Selected Living Cost Indexes that provide a better indication of the cost of living than the CPI.

The ABS publishes the latest CPI figures in its Consumer Price Index, Australia release as well as answers to common questions on how to calculate and interpret the CPI and similar cost-of-living metrics.

This Reserve Bank of Australia 'explainer' on inflation and its measurement discusses inflation and the calculation and limitations of the CPI.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: indexation, inflation, nominal, payment.

The contingency reserve is an allowance within the budget for policy changes or other items that the government expects but cannot allocate to specific government programs or publish separately in the budget.

There is a range of items that may be put into the contingency reserve. These include:

- the 'conservative bias allowance' that accounts for the tendency for the costs of some existing government programs (particularly demand-driven programs) to be higher than estimated

- This is typically the largest component of the contingency reserve and is calculated as a fixed share of total expenses (after adjusting for goods and services tax payments to the states).

- items that are too sensitive to be disclosed separately, such as those that are commercial-in-confidence or that affect national security

- a provision for underspends in the current financial year

- decisions that are taken by government but were not announced before the budget, or were made too late to be included in individual agency estimates. The total value of these decisions are published in the budget papers as 'decisions taken but not yet announced'

- expenses where the final cost depends on negotiations with another entity such as state and territory governments

- provisions for other specific events and pressures that are expected to affect the budget estimates but have not yet taken place.

Funds in the contingency reserve are not yet agreed to by Parliament (through an appropriation) but are still included to ensure that budget aggregates reflect expected outcomes. The value of the contingency reserve changes over time as new and updated information is available.

When funds held in the contingency reserve are appropriated to a government entity, their value is removed from the contingency reserve and allocated to a specific government entity or program.

The contingency reserve is included as an aggregate expense in the budget papers and updated at every Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook. The general practice has also been for items in the contingency reserve not classified as commercial-in-confidence or national security-in-confidence to be identified in the budget update released before a general election, known as the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

The 2021-22 Budget (Statement 6: Expenses and Net Capital Investment of Budget. Paper. No. 1) provides an example of how the contingency reserve is presented in the budget (Table. 6.17) and how the conservative bias allowance component is calculated (Pages 193-194).

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget aggregates, budget paper, demand-driven program, expense, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook, program

D-F

Government debt refers to the amount of money that the government owes its lenders at a particular point in time. In broad terms, it measures how much successive governments have spent over the receipts they have collected. Going into debt allows the government to fund activities that it could not otherwise afford.

For example, suppose the budget is in a cash deficit (receipts are lower than payments) and the government wants to increase the age pension payment. There are three options available:

- reduce other spending to find savings to pay for the pension increase

- increase receipts, for example by raising taxes

- borrow money from investors (go into debt) to fund the spending.

When an individual borrows money, they generally take out a loan. When the Commonwealth Government borrows money, it generally sells financial instruments, including bonds, which are collectively called 'Australian Government Securities'. These are bought by investors who receive interest from the government at specified intervals and the principal at maturity, which is an agreed term ranging from months to several decades. The borrowing cost the government incurs through debt is called 'public debt interest'.

There are two main measures of government debt, gross debt and net debt, and the numbers for each are often very different from each other.

In the budget papers, gross debt is the sum of Australian Government Securities on issue, based on their value when the securities were issued (their 'face value'). While gross debt reflects the total amount of Commonwealth Government debt, it does not include any of the government's financial assets that partly offset that debt, or any smaller debts that are not Australian Government Securities. For this reason, only looking at gross debt without net debt could give an incomplete picture of the government's financial position.

Net debt is the sum of selected financial liabilities (including government securities, loans, deposits held, and other borrowings) minus the sum of selected financial assets (including cash and deposits, advances paid, and investments). In the net debt calculation, Australian Government Securities are valued as the price they are currently trading at (their 'market value') rather than their face value.

Compared to gross debt, net debt is a better indicator of the strength of the government's financial position. While net debt is a widely used indicator of the financial health of a government, it has its own limitations. See the net debt entry in this glossary for more information.

Within the budget papers:

- Statement 7: Debt Statement of Budget Paper No. 1 provides information on current and projected government debt, including the assumed interest rates on future borrowings and the share of bonds held by non‑resident investors.

- Statement 10: Australian Government Budget Financial Statements of Budget Paper No. 1 provides complete projections of the government's fiscal position, including projections of net debt.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: gross debt, net debt, payment, public debt interest, receipt

Decisions taken but not yet announced (DTBNYA) is a component of the contingency reserve. The size of DTBNYA and its composition varies from time to time. This is because DTBNYA are policy decisions that have been taken by the Australian Government and included in the budget aggregates, but the details and costs of which have not yet been disclosed to the public.

DTBNYA includes new policies not yet announced as well as policies that have been announced but whose costs cannot be published. The total values of new DTBNYA for receipts and payments are presented in the summary tables in Budget Paper No.2. Note that the contingency reserve includes only the amounts for DTBNYA for payments, not receipts.

There are several reasons why policy decisions may not be announced, or amounts cannot be published.

- The announced policy may be subject to commercial-in-confidence restrictions or its disclosure could prejudice national security. For example, the cost of the 2021-22 Budget measure, COVID19 Vaccine Manufacturing Capabilities, was listed as not for publication (nfp) due to commercial-in-confidence sensitivities. Similarly, the fiscal impact of new listings to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme is usually reported as not for publication.

- Some policies may have been finalised very late in the budget process. For example, the 200405 Budget included an allowance for the impact of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission’s living wage case decision which was released less than a week before the budget.

- The government can choose when it announces its policy decisions and may include some policies within DTBNYA in order to announce them later.

For further information see the PBO’s budget explainer no 2/2021 The Contingency Reserve on DTBNYA and its budget treatment. At the 2022-23 Budget, DTBNYA was referred to as ‘Decisions taken but not yet announced and not for publication’.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget aggregates, contingency reserve, measure, not for publication

A demand-driven program is a program where the required amount of funding is determined by the number of users, which can change over time. Each demand-driven program has its own eligibility criteria and can be accessed by anyone who meets the criteria.

Many government benefits and payments are demand-driven programs. For example, the JobSeeker payment provides financial support to anyone who meets the eligibility criteria, which includes being unemployed and looking for work, and meeting income and assets tests. The amount of funding required for the JobSeeker payment increases if there is a sudden rise in the number of people who are unemployed, as more people apply and become eligible for the payment — this is known as an increase in the demand for the program. Likewise, payments would be expected to fall in line with reduced unemployment. The age pension is another example of a demand-driven program.

A demand-driven program has no fixed limits on the number of places available or the number of people who can access the program, as long as eligibility criteria are met, which means funding cannot be capped. This can make it hard to predict spending, and final expenses can be higher or lower than expected.

Across all programs, the total difference between the expected and the final costs due to changes in demand is reflected in the 'parameter and other variations' section in the budget papers.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget paper, capped funding, expense, parameter, payment, program

Departmental funding is managed and controlled directly by government agencies, with the head of the agency having responsibility for managing the funding. Typically, departmental funds are used for the purpose of day-to-day operations and to support programs for which the agency has responsibility. Departmental funding is distinguished from administered funding, which is managed by government agencies on behalf of the government as a whole.

For example, the government provides departmental funding to Services Australia, the government agency that provides income support payments such as the age pension. Services Australia uses this departmental funding to pay for the staff and equipment it needs to make income support payments to the public. The income support payments themselves are administered funding, which is governed by eligibility rules set out in legislation rather than being directly controlled by Services Australia.

Departmental expenses are generally much smaller than administered expenses and vary across time. For example, departmental expenses accounted for around 14 per cent of total expenses in 2019-20 and around 6 per cent of total expenses in 2020-21. They include the organisational costs of government agencies as well as the costs of corporations within the general government sector, such as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation; the costs of the Australian Defence Force; and the costs of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, which is under the control of the National Disability Insurance Agency.

While 'departmental' is a term usually associated with expenses (staff, office buildings and equipment), it can also relate to capital and revenue. Departmental funding includes the capital funding for the Department of Defence, mainly for military equipment. An example of departmental revenue is where an agency charges to recover the costs associated with managing a program or providing a service (for example the Australian Bureau of Statistics may charge users for providing custom statistical information that is not publicly available).

Details of departmental funding across all Commonwealth Government agencies are published in the budget in Budget Paper No. 4: Agency Resourcing. Commonwealth Government agencies also report their departmental items in greater detail in their Portfolio Budget Statements (budget information for a Minister's area of responsibility) and in their annual reports.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: administered funding, budget, budget paper, expense, Portfolio Budget Statement, program, revenue

Elasticity is a technical term for a type of calculation used in economic and fiscal analysis, which usually relates to how quantities respond to changes in prices. It is expressed numerically as a measure of the percentage change of an economic variable in response to a percentage change in another related variable. Elasticity values can be positive or negative. The larger the value the more elastic or responsive one variable is to a change in a different variable.

Some examples of common types of elasticity include:

- A price elasticity of demand of −0.2 would indicate a negative elasticity and mean that demand has a low responsiveness to changes in price. In this case, a 10% increase in the price of a product would lead to only a 2% reduction in the quantity consumed.

- An income elasticity of demand of 1.2 would indicate a strong positive elasticity and would show that with every 1% increase in a person’s income the quantity of a particular product consumed would increase by 1.2%.

- A labour demand elasticity of −0.5 would indicate a negative elasticity and show that if wages increase by 1% there would be a 0.5% decrease in the number of people employed.

- A price elasticity of supply of 2.5 would be a strong positive elasticity and mean there is a high responsiveness to changes in the price. In this case, a 1% increase in the price of a product would lead to 2.5% more of the product being supplied to the market.

Elasticities are widely used when determining the impact of potential policies on the amount of revenue (or expenses) that would be earned (or incurred) by the government.

For example, if a policy measure proposes to increase the wage for a group of workers, then the labour demand elasticity for this group of workers would affect the amount of tax revenue collected by the Australian Government, as shown below.

- If there were 10,000 workers in an industry, each earning $42,000 a year, then the annual amount of tax revenue collected would be $45.2 million ($4,520 in tax per worker x 10,000 workers). If a policy measure were to increase the annual wage for these workers to $42,420, then this would represent a 1% wage increase. This wage increase would lead to an increase in the tax paid per worker to $4,600 and, assuming no change in the number of workers employed, increase tax revenue by $0.8 million.

- Now, if this industry had a labour demand elasticity of say −0.5, then this would mean that the number of workers employed in this industry would decrease by 0.5% to 9,950. The amount of tax revenue collected under the new policy would now be $45.8 million ($4,600 in tax per worker x 9,950 workers), leading to an increase in tax revenue of $0.6 million.

- However, if the industry had a stronger negative labour demand elasticity of say −2, then this would mean a decrease of 200 workers to 9,800. The amount of tax revenue would then be $45.1 million ($4,600 in tax per worker x 9,800 workers), which represents a decrease in tax revenue of $0.1 million.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: expenses, measure, revenue, tax revenue

An equity investment is a payment in exchange for an ownership stake in a business and a share of any profits. The money invested is called an 'equity injection' and the profits paid back are called dividends. In the Commonwealth Government budget context, examples of equity investments include:

- direct government ownership of shares in companies through Commonwealth Government investment funds

- the government's sole ownership of NBN Co Limited to finance the delivery of the National Broadband Network.

These two examples show two different purposes of government equity investments.

- In the case of equity investments made by government investment funds, the investments are intended to generate revenue to be spent on specific policy objectives.

- In the case of investments such as NBN Co Limited, a government equity injection is a form of alternative financing to pay for a project. Under direct funding, such as a grant to build a road, the government does not expect to be repaid. With equity injections and most other types of alternative financing, such as government loans, the government provides financial resources in return for a financial asset. Equity injections can support projects that are large or where the risk profile makes private sector investment unlikely. Governments will generally take into account the broader social or public benefits of the investment.

In either case, the government may receive a flow of dividends from ownership and can sell its share of the investment at a later date. The effect of equity injections on the government's fiscal position can be more uncertain than that of direct funding. For example, the value of an ownership stake can change over time, depending on the valuation of the business. Very limited information is provided in budget documents about these revaluation‑related impacts of equity investments. Estimates of the valuation of individual equity investments, such as the National Broadband Network, are usually located within the annual reports of the administering government department rather than the budget papers.

Within the budget papers, information about equity investments includes:

- Statement 7: Debt statement of Budget Paper No. 1, which provides details of the major assets and liabilities on the Commonwealth Government's balance sheet

- Statement 10: Australian Government Budget Financial Statements in Budget Paper No. 1, which shows the total dividends received from equity investments, and the estimated amount of equity investments held by the government within its net financial worth.

The PBO's report no. 01/2020, Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees contains more information on equity, other alternative financing arrangements, and their impact on the budget.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: alternative financing, budget, budget paper, debt, grant, net, net financial worth, program

Expense in the budget context refers to the cost of providing government services, excluding costs related to revaluations such as the write down of assets. Examples include spending on programs such as the age pension or Medicare, funding provided to the states and territories for public hospitals, or the wages paid to Commonwealth Government employees.

Expenses are recorded when costs are incurred, regardless of whether any cash is paid. This reflects an accrual accounting framework. This is distinct from payments, which are recorded when cash amounts are paid. For example, the expense associated with a Commonwealth Government employee's long service leave is recorded every year once an employee is eligible for the leave; however the cash payment will only be recorded when the employee takes their long service leave.

Expenses are presented in a number of different ways in the budget papers. For example, Statement 6: Expenses and Net Capital Investment of Budget Paper No. 1 breaks down the estimates of expenses by government function (such as health, social welfare and education) as well as information on the twenty government programs with the largest expenses.

Statement 10: Australian Government Budget Financial Statements of Budget Paper No. 1 reports expenses in accordance with budget accounting standards. The financial statements and the associated notes provide detailed information on expenses for wages and salaries (largely wages for Commonwealth Government employees), the supply of goods and services (for example providing pharmaceuticals and health services), grants (largely, funding to the states and territories for services they deliver), and personal benefits (largely, social security pensions and allowances).

Budget Paper No. 4: Agency Resourcing reports expenses according to the Commonwealth Government agency that receives the funding. This funding is further split into administered and departmental expenses.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: accrual accounting, administered funding, budget, budget paper, departmental, net capital investment, payment, program, revenue

The Final Budget Outcome (FBO) provides the Commonwealth Government's fiscal outcomes over the past financial year. It shows how much the government actually spent or received rather than how much it expected to spend or receive, and whether a projected budget surplus or deficit actually occurred.

The Final Budget Outcome is the last of three main annual budget reporting documents required by the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998. The other two main annual budget reporting documents are:

- the budget, that sets out the economic and fiscal outlook and the government's fiscal strategy

- the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, that provides updated information on the government's fiscal performance that can be assessed against the fiscal strategy set out in the budget.

The Charter of Budget Honesty requires that the Final Budget Outcome is released no later than three months after the end of the relevant financial year.

As an example, the 2018‑19 Final Budget Outcome was released in September 2019 and included:

- Part 1: information on budget aggregates for 2018‑19, including analysis of the government's cash flows, revenue, expenses, net capital investment and the balance sheet (net debt, net financial worth and net worth)

- Table 1 shows the budget was forecast to be in deficit in underlying cash balance terms for 2018‑19 but the actual outcome was a balanced budget as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) (neither surplus nor deficit).

- Table 3 shows how much tax was actually received from each major source of cash receipts, and can be compared to what was expected in the budget and MYEFO (Table 7 in Statement 4: Revenue of Budget Paper No. 1 in the 2019‑20 Budget and Table 3.10 in Part 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook of the 2018‑19 MYEFO).

- Part 2: Commonwealth Government financial statements for 2018‑19, covering the general government sector as well as the public financial corporations and public non-financial corporations sectors

- Part 3: details on Australia's federal and state financial relations for 2018‑19, including actual payments to states and territories from goods and services tax revenue, and Commonwealth Government payments for services delivered by states and territories, such as for public hospitals and schools

- Appendix A, Expenses by function and sub-function: details how much was actually spent on each major function of government, and can be compared to the forecast spending in the equivalent tables in the budget and MYEFO (Table 3 in Statement 5: Expenses and Net Capital Investment of Budget Paper No. 1 2019‑20 Budget Table 3.23 in Attachment C of the 2018‑19 MYEFO).

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget aggregates, Charter of Budget Honesty, expense, financial year, general government sector, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, net capital investment, net financial worth, public non-financial corporation, revenue

A financial statement is a report showing the financial activities and performance of an entity. The financial statements in the budget papers present a picture of the Australian Government’s fiscal position and outlook for the period of the forward estimates, being the current budget year and the 3 following years.

Three financial statements are included in the budget papers – the balance sheet, operating statement, and cash flow statement.

- The balance sheet shows the government’s financial position at a point in time (usually the end of a financial year). It lays out what the government owns (financial and non-financial assets) and what the government owes to others (liabilities), and presents budget aggregates such as net worth, net financial worth and net debt.

- The operating statement presents details of changes to the government’s financial position over a financial year. This can be through government revenue, such as taxation revenue or sales of goods and services; through expenses, such as the payment of wages and salaries or the delivery of government programs; or through revaluations of existing assets. The operating statement includes budget aggregates, such as the operating balance and fiscal balance.

- The cash flow statement shows how government receives and uses cash over a period of time (usually a financial year), covering cash flows related to operating activities, investments and financing activities. It presents budget aggregates such as the underlying cash balance and the headline cash balance.

The financial statements in Budget Paper No. 1 report consolidated outlooks for the general government sector, public financial corporations sector (which includes the Reserve Bank of Australia), public nonfinancial corporations sector (which includes NBN Co) and the total nonfinancial public sector. The statements are generally prepared consistent with the Australian Bureau of Statistics Government Finance Statistics methodology.

The financial statements are presented in line with the Uniform Presentation Framework agreed between the Australian, state and territory governments. This framework aims to ensure that government financial information is presented on a consistent basis in line with the relevant Australian Accounting Standard (AASB 1049). The financial statements are accompanied by several additional tables providing more detail for particular items.

In the 2022-23 Budget, the forecast financial statements can be found in Budget Paper No.1, Statement 9. Forecast financial statements are also found in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook update, published around 6 months after the budget. Unaudited financial statement outcomes are published in the Final Budget Outcome, published no later than 3 months after the end of the relevant financial year, with fully audited outcomes presented in the Australian Government’s Consolidated Financial Statements, published by the end of November each year.

For further information:

- see Appendix A in the PBO’s research report no 01/2020 Alternative financing of government policies: Understanding the fiscal costs and risks of loans, equity injections and guarantees for a visual glossary of each financial statement

- see Notes to Financial Statements for a detailed explanation of the accounting basis.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: budget, budget aggregates, financial year, forward estimates, general government sector, headline cash balance, Final budget Outcome, fiscal balance, Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, net debt, net financial worth, net worth, underlying cash balance

A financial year (FY), sometimes known as a fiscal year or budget year, is a 12‑month period used for financial reporting and taxation purposes that does not necessarily start on 1 January. In Australia, a financial year starts on 1 July and ends on 30 June. As dates differ between countries, some companies can also vary their individual financial years in order to match the financial reporting requirements for their related businesses overseas.

The peak holiday and retail season for Australia occurs in December and January so the timing of the financial year allows financial reports and tax returns to capture the whole impact of those seasons. If the financial year started on 1 January the total impact of this peak would be spread across two different reporting periods.

Ending the financial year on 30 June rather than 31 December also allows the peak activity around financial reports and tax returns to occur around and after June, rather than around and after December when more employees are likely to be taking breaks.

The fiscal balance (FB) is one of several indicators known as 'budget aggregates' that measure the impact of the government's budget on the economy. Along with the underlying cash balance, or sometimes the net operating balance, the fiscal balance is one of the budget aggregates that may be referred to in discussions of whether the budget is in a surplus or a deficit position.

Broadly speaking, the fiscal balance is equal to the government's revenue (for example from taxes) minus its expenses (from providing services such as Medicare and income support such as the age pension), adjusted for government capital investments such as military equipment (known as 'net capital investment in non-financial assets') when they are acquired or sold. This compares with the net operating balance which accounts for capital as it is used (through depreciation).

If the government has more revenue than it needs to finance its expenses and investment spending, the fiscal balance is positive and there is a surplus on a fiscal balance basis. If the government has to borrow money to finance its planned spending and investments, the fiscal balance is negative and there is a deficit on a fiscal balance basis.

The fiscal balance for a given financial year records revenue when it is earned and expenses when they are incurred, regardless of when any money is actually received or paid out during that financial year. For example, the fiscal balance records revenue from company taxes in the financial year a company earns the income even though it may not have to pay the tax until the following financial year. This accounting method is called accrual accounting and differs from the method used for another commonly used budget aggregate, the underlying cash balance, which is calculated on a cash accounting basis and records receipts and payments of cash when they occur.

The government publishes a breakdown of the fiscal balance at each budget update, showing that it can be viewed as revenue minus expenses (also known as the 'net operating balance') less net capital investment in non-financial assets. It also shows the difference between the fiscal and underlying cash balances. Examples of this difference can be seen in Table 3.2 in Statement 3: Fiscal Strategy and Outlook of Budget Paper No. 1 in the 2021-22 Budget and Table 3.2 in Part 3: Fiscal strategy and outlook of the 2020-21 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: accrual accounting, budget, budget aggregates, cash accounting, expense, headline cash balance, net capital investment, net operating balance, non-financial asset, payment, receipt, revenue, underlying cash balance

Fiscal policy refers to the government's financial operations and management, including how much the government spends and on what, how much income the government has and from what sources, and how much the government borrows. 'Fiscal' means relating to government money.

Examples of fiscal policy include policies related to:

- revenue, such as the rates and scope of taxes like income tax and company tax

- expenses, such as the level of income support payments like the age pension and who is eligible for them

- the size and role of the government as a whole, such as how much the government should seek to redistribute income, and whether there should be restrictions on tax as a share of the total economy (a 'tax cap'), or on how much the government can borrow (a 'debt ceiling').

Fiscal policy can:

- influence the economy directly or indirectly. For example, fiscal policy has a direct influence when the government purchases equipment, and an indirect one when the government provides payments to, or taxes, households and businesses, changing their spending or saving behaviour.

- be expansionary or contractionary. That is, influencing the economy to grow faster or slower, respectively, than it would have without the government's actions.

- work over the short term and long term. For example, fiscal stimulus policies seek to avoid or reduce the severity or duration of a recession, while governments implement a range of other fiscal policies to achieve longer‑term objectives, such as preparing the economy for the changes associated with an ageing population.

- be counter cyclical or pro cyclical. If the economy was heading into a downturn and fiscal policy was reducing the severity of the downturn, policy would be counter cyclical; if fiscal policy was intended to offset the downturn but actually reinforced it, it would be pro cyclical.

Fiscal policy can be distinguished from monetary policy. In Australia, monetary policy is set independently by the Reserve Bank of Australia, which sets official interest rates. For example, if it thinks inflation is above its target, the Reserve Bank can raise official interest rates to help bring it back down. Together, fiscal and monetary policy are aspects of 'macroeconomic policy', or policies to do with the operation of the economy as a whole. Different economists have different views about these two arms of policy, including about the relative effectiveness of monetary policy versus discretionary fiscal policy.

In Australia, the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 sets the legal framework for Commonwealth Government fiscal policy. The Charter sets out that the objective of fiscal policy is to maintain ongoing economic prosperity and the welfare of Australians. It includes obligations for the contents and frequency of budget documents, and requires governments to set out and report against a medium-term fiscal strategy based on principles of sound fiscal management.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: automatic stabilisers, budget, Charter of Budget Honesty, expense, fiscal stimulus, recession, revenue

Fiscal space is a concept used to express the government’s ability to undertake new or additional public spending without impairing its ability to service its debt. Broadly, the concept refers to how much capacity a government has to invest in new programs or initiatives, such as investing in infrastructure to adapt to climate change. Fiscal space can be created through increased government revenue, reduced or re-prioritised expenditure and/or increased borrowing capacity.

The concept of fiscal space is sometimes used when considering funding for programs that may drive growth in the economy or have longer term welfare benefits. Outlays of this nature are sometimes discussed as being able to pay for themselves over the long run, since they are likely to expand the productive potential of the economy and thereby create the fiscal space that is needed to pay for them. Such arguments are difficult to reliably assess. PBO costings typically do not include such effects (see the PBO’s information paper no 3/2017 Including broader economic effects in policy costings).

The availability of fiscal space is often discussed in relation to developing and emerging market economies. For example, funding an infrastructure project may create additional jobs in the economy and funding to build a new school or hospital may generate gains to human capital.

Decisions of government will sometimes be framed as increasing fiscal space; for example, by increasing revenue, reducing or re-prioritising expenditure, increasing the government’s borrowing capacity or reducing its cost of borrowing. Each of these strategies can be part of increasing the ability of government to take action in a sustainable way in the future, although it is typically the combined impact of all policies that is most relevant to increasing or decreasing fiscal space.

For further information:

- on the concept of fiscal space and how it relates to a country’s macroeconomic situation see the report by the International Monetary Fund from June 2005 Volume 42 no 2 Back to Basics – Fiscal Space: What It Is and How to Get It

- on over 30 indicators of fiscal space and a database of over 200 countries see the working paper no 8157 by the World Bank from August 2017 A Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space.

Related terms in the PBO glossary: debt, expense, program, revenue

Fiscal stimulus refers to government policies that aim to avoid or reduce the severity or duration of an economic downturn, such as a recession. Paying income support recipients, such as pensioners, a one‑off top‑up payment during a recession is an example of fiscal stimulus.

Fiscal stimulus is described as 'discretionary' fiscal policy — that is, it requires an explicit decision by the government. This is in contrast to parts of existing government policy known as 'automatic stabilisers' that adjust automatically to changes in economic conditions such as recessions. For example, during the Global Financial Crisis of 2007‑09:

- one‑off payments to low and middle income individuals and households with dependent children were part of a fiscal stimulus package of new policies in response to the crisis. These people were likely to spend a sizeable share of the payment, which would help to stimulate the economy by creating demand for goods and services in the short term.

- increases in the total amount of unemployment benefits paid were an automatic stabiliser. Without any change in policy, the total number of recipients of the unemployment benefit increased because the number of unemployed people increased.

Both discretionary fiscal stimulus and the automatic stabilisers are said to work 'counter cyclically' (that is, against the economic cycle). The kinds of policies that should be implemented depend in part on what has caused the economic downturn.