Information paper no. 01 | 2020 | Date issued: 15 January 2020

This information paper explains our approach to determining the behavioural assumptions we apply when estimating the cost of policy proposals.

Overview

A key role for the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) is to provide advice to parliamentarians on the estimated financial implications, or ‘cost’, of policy proposals they are considering. We provide independent advice that can be interpreted in the same way as the costings presented by the government in the budget, prepared to the same standards and using the same concepts.

Our advice is typically sought by members of the Opposition and minor parties as they cannot ask government departments for such advice. We provide our costing advice on a confidential basis if the parliamentarian requests it, and therefore it is the decision of the parliamentarian on whether or not to publicly release the costing.

A costing critically depends on the details of the specification of the proposed policy, as well as our assumptions about how people affected by the policy would be likely to change their behaviour in response to the policy.

This information paper explains our approach to determining the behavioural assumptions we apply when estimating the cost of policy proposals. We are guided by three principles. Behavioural assumptions aim to be:

- consistent across similar policies

- backed by empirical evidence

- informed by expert advice.

Given that a policy costing can be particularly sensitive to assumed behavioural responses, we are committed to transparency around these assumptions. The advice we provide to parliamentarians includes detailed information on the assumptions that have been made in preparing the costing and the basis for these assumptions. Where assumptions are particularly uncertain, we may include sensitivity analysis in our advice to parliamentarians.

To further improve transparency and gather feedback, this paper presents a consolidated list of the behavioural assumptions we have made in costings that were publicly released during 2019 (see Appendix A). In particular, this list includes behavioural assumptions that we used in costings in the 2019 Post-election report of election commitments. We welcome feedback on any of the assumptions included in this list, including the provision of alternative evidence where available. We invite you to email any comments to feedback@pbo.gov.au.

1 Policy costings and behavioural assumptions

A policy costing provides an estimate of the impact that a proposed policy would have on the budget if it were implemented. The PBO information paper What is a Parliamentary Budget Office costing? explains what a costing is designed to capture and how a costing estimate is generated1. It explains that a key role for us is to determine the most appropriate data, models and assumptions to use in order to estimate the budget impact of a policy proposal. It also highlights that costing estimates critically depend on the details of the policy specification and the assumptions made about how people and organisations affected by the policy would be likely to respond to it.

In this paper, we explain how we determine the behavioural assumptions that underpin our costings.

Our costings always capture how individuals, businesses or organisations who are directly affected by a proposed policy would be likely to respond to it. Some policy proposals are designed to induce a particular behavioural response, while others may induce unintended behavioural responses. In either case, it is necessary to make assumptions about how those affected by a proposal may respond in order to accurately estimate the budget impact of a proposal. Sometimes we determine that these responses may be significant and would materially affect a costing, while in other cases we determine that there may be no behavioural response that needs to be taken into account. Some behavioural responses can be precisely estimated, while others are much more uncertain.

In broad terms, there are two types of behavioural responses we consider when undertaking a costing. First, there are the behavioural responses that would be expected to have a temporary impact on the budget. These are driven by individuals or businesses changing the timing of their spending or saving behaviour around the start (or end) date of a proposal. The introduction of a temporary investment incentive, for example, would be expected to lead some businesses to change the timing of investments around the period that the proposal applies to take advantage of the incentive. The second type of behavioural response we consider is one that has an ongoing budget impact. A proposal to increase the highest marginal tax rate, for example, may lead some high-income earners to find ways to permanently reduce their taxable income, affecting tax collections in all years after the proposal is implemented.

Our costings do not generally capture the fiscal impacts of the potential broader economic impacts of policy proposals, such as from changes in aggregate prices, employment levels or productivity growth. These broader economic impacts are not usually quantified in our costings unless the funding mechanism is specified, and there is compelling evidence on the direction, size and timing of the broader economic effects. Where we do not include broader economic effects, our advice to parliamentarians does include a qualitative discussion of these impacts when we consider they could be material. Further discussion about estimating broader economic impacts is provided in our information paper Including broader economic effects in policy costings2.

In determining the direction and magnitude of the assumptions we make about behavioural responses, we apply three principles. These are outlined in Figure 1 and discussed further in Sections 2 to 4 of this paper.

Figure 1: Three principles applied in determining behavioural assumptions

We are committed to transparency around the behavioural assumptions that we apply in our costings. This includes being transparent about our assumptions, and the justification for these, in our costing advice to parliamentarians, as well as providing sensitivity analysis where assumptions are particularly uncertain. This is discussed further in Section 5.

As part of our commitment to transparency, we have provided a consolidated list of behavioural assumptions in the online assumptions glossary. This list details behavioural assumptions we have made in costings that were published in 2019, including those used for costings in the 2019 Post election report of election commitments.3 Where available, links to any research or data used in determining the assumptions have been provided.

2 Consistency across policies

A principle that the PBO applies when determining behavioural assumptions is to take a consistent approach across policies. Assumptions are, of course, updated over time to reflect new information and changes in the broader environment. This implies that when two policy proposals are expected to have a similar impact on similar groups, we would generally assume similar behavioural responses. Conversely, when one policy proposal has a relatively large impact on those affected and another has a small impact, we would expect a stronger behavioural response to the proposal that has a larger impact. This principle assists comparisons across different costings.

2.1 We draw upon behavioural assumptions for policy proposals we have costed before

We have costed a wide range of policy proposals over time. A starting point for determining the behaviour assumptions that will be applied in any new costing is to understand whether we have previously costed the same or a similar proposal and, if so, what behavioural assumptions were used. Before applying a previous assumption, however, we have to determine that it is still applicable. For instance, we explore whether new data or evidence is available that either supports the existing assumption or requires it to be revised. We also examine whether there have been changes to government policy or economic conditions that suggest a different behavioural response may occur.

We regularly review completed policy costings, including reviewing the behavioural assumptions that were applied, to identify areas for improvement in future costings.

2.2 Our costing models usually imply that behavioural responses will be proportionate to the policy impact

Many of our costings are estimated using administrative data for individuals, families, businesses or other affected groups to simulate the effects of a policy proposal. These micro-simulation models generally incorporate assumptions that any responses to changes in income tax, prices or costs would be proportionate to the magnitude of the change. These assumptions are applied through elasticities4. This helps to ensure proportionality of behavioural impacts across two or more proposals affecting a similar policy area, such as the personal income tax system, child care subsidies, or the out-of-pocket costs of health care.

Box 1 illustrates how taxable income elasticities are used to capture behavioural responses to changes in marginal tax rates and how these vary across individuals, depending on their income levels.

2.3 We review assumptions used when costing budget measures

Other government agencies make behavioural assumptions when costing budget measures. In the interests of preparing costings consistent with those prepared for the government, we often draw upon these assumptions in our own costings. Before accepting these assumptions, we thoroughly assess them, just as we scrutinise the assumptions that we have made before. We also look to consult with other agencies to understand their analysis, thought processes and the information they have used to determine their assumptions.

Box 1: Taxable income elasticities help ensure consistency across personal income tax costings

Policies that make changes to personal income tax rates and thresholds are likely to lead some individuals to look for ways to change their taxable income. If marginal tax rates are increased, for example, some individuals may look to find additional deductions, delay the realisation of capital gains, or restructure their investments to reduce their taxable income, which will reduce the amount of tax raised by the change in policy. Such a policy may also lead to individuals choosing to work more or less, but there is considerable uncertainty regarding the direction, magnitude and timing of the effect of personal income tax changes on labour supply, and this is not usually incorporated into PBO costings.

Taxable income elasticities measure how responsive individuals are to changes in marginal tax rates. Specifically, they measure the percentage change in an individual’s taxable income that is expected to result from a percentage change in their net-of-tax rate. The net-of-tax rate is one minus the individual’s marginal tax rate; it measures the proportion of an additional dollar of income that an individual would keep after tax is taken out. For instance, the highest marginal tax rate is currently 47 per cent (including the Medicare levy). For taxpayers facing this rate, their net of-tax rate, shown as a percentage, is 53 per cent.

We assume that individuals with a taxable income above the highest threshold (currently $180,000) have a taxable income elasticity of 0.2. These individuals are assumed to reduce their taxable incomes in response to increases in the highest marginal tax rate, and increase their taxable incomes in response to decreases in the highest marginal tax rate. For instance, a 2019 election commitment by the Australian Greens involved increasing the highest marginal tax rate by two percentage points (see Introduce a 35 per cent minimum tax rate on incomes above $300,000 and make the deficit levy permanent PER618); our elasticity assumption reduced the revenue gain from this proposal by around 40 per cent relative to a scenario in which no behavioural response is assumed.

Individuals with a taxable income below the highest threshold are assumed to have a taxable income elasticity of zero. It is assumed that these individuals would not adjust their taxable incomes in response to a change in marginal tax rates, reflecting that there are limited options available to lower-income earners, particularly wage and salary earners, to restructure their investments.

There is a broad range of taxable income elasticities estimated in the empirical literature across a number of developed economies. The elasticities we use are close to the median estimates in the literature, and setting a higher elasticity for higher-income earners is consistent with the literature.5 Having a standard approach to taxable income elasticities helps to ensure behavioural responses are consistent across costings that make changes to income tax rates and thresholds.6

3 Empirical research

Another principle the PBO applies in determining behavioural assumptions is that, wherever possible, they should be informed by empirical research or analysis.

3.1 Peer-reviewed academic research is usually the ‘gold standard’ for quantifying behavioural responses

There are numerous empirical studies in academic literature that estimate price or taxable income elasticities, as well as other behavioural responses to policy changes. Some of these studies show very robust results and others suggest significant variations in responses across countries, sectors or time.

While we aim to back up all behavioural assumptions with evidence from empirical literature, it can often be challenging to find academic studies that directly apply to a specific policy proposal. For instance, the best evidence we may be able to obtain might be an empirical study from another advanced economy that estimates the behavioural response of a similar policy to the one proposed. Such research can still be extremely useful in providing evidence of how, and to what extent, those affected may respond to particular policy changes. Figure 2 outlines a set of questions we ask ourselves to determine whether a particular empirical study should inform a behavioural assumption.

Figure 2: How the PBO evaluates an empirical study for use in a costing

As a general rule, empirical studies help to define a range within which a behavioural response is likely to fall. The more reliable the study or the collection of studies, the narrower this range is likely to be. There are many cases, however, where a reliable and applicable study is difficult to obtain and we need to rely on other evidence.

3.2 There is often data available for us to undertake our own empirical research

We have access to high-quality historical data that may be used to estimate behavioural responses to past policy changes, or to help inform a behavioural assumption. Our own research can be used to complement academic research, or to inform cases where reliable academic or other empirical research is not available. Box 2 provides a case study of an election commitment costing where we undertook empirical research to inform a behavioural assumption.

Box 2: Case study – Medicare for cancer treatment

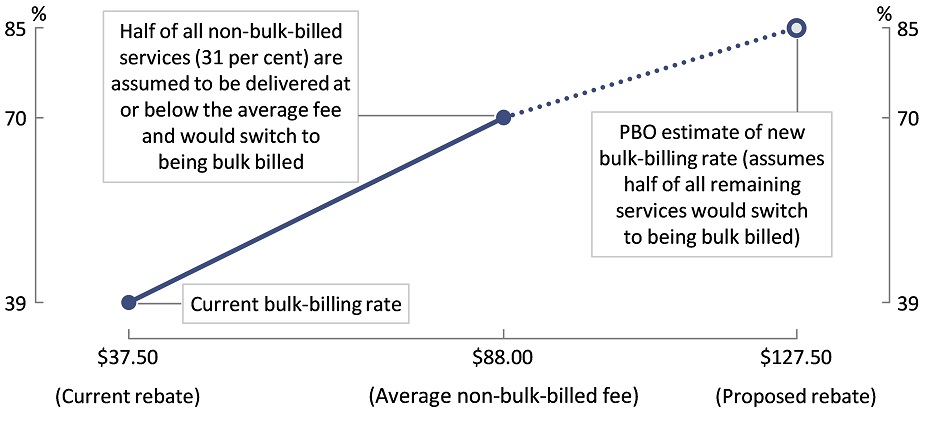

A 2019 election commitment made by the Australian Labor Party, and costed by the PBO, was a proposal to amend the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) to reduce out-of-pocket costs for cancer patients. The Medicare cancer plan (PER372), amongst other things, would have introduced a new MBS item covering visits to oncologists and cancer surgeons for the purpose of providing ongoing treatment following a cancer diagnosis. The proposed MBS item would attract an 85 per cent rebate of $127.50 and would be required to be bulk billed.

The proposed rebate would be significantly higher than both the rebate for existing items and the average fee currently charged for non-bulk-billed services. Given this, we considered that the proportion of affected services that would be bulk billed under the proposal would increase significantly. We used the existing relationship between bulk-billing rates under the current rebate and the percentage of services where the practitioner accepts at or below the average fee for non bulk billed services to project bulk billing rates under the proposed rebate increase. This is illustrated for MBS item 105 (cancer surgeons) in Figure 3, where the bulk-billing rate is assumed to increase from 39 per cent to 85 per cent as a result of the increase in the rebate.

Figure 3: Cumulative percentage of services provided for different fees/rebates – MBS item 105 (cancer surgeons)

(a) Currently, 39 per cent of services are bulk billed. Half of the remaining 61 per cent of services (31 per cent) are assumed to be delivered at or below the average non-bulk-billed fee.

(b) Given that the proposed rebate is well above the average non-bulk-billed fee, we assume that half of all remaining services (15 per cent) would switch to being bulk billed.

4 Expert advice

The third principle the PBO applies in determining behavioural assumptions is that assumptions should be consistent with theory and, wherever possible, tested with experts. Expert advice is particularly useful for new and novel proposals where there is little empirical evidence to draw upon. We ensure that any consultations with experts are conducted in a way that maintains the confidentiality of requests from parliamentarians.

4.1 We look to draw upon theoretical literature to understand the likely impact of behavioural responses

Theoretical literature can help inform the likely direction of any behavioural response and whether the magnitude of the budget impact would be small or large. For instance, economic literature suggests that reducing the price of a particular product or service (by introducing a subsidy, for example) will usually result in an increase in demand for the particular product or service. There may also be theoretical models in literature that indicate the degree of price sensitivity of consumers for particular products or services.

Having drawn upon theoretical literature, we often look to estimate the financial impact of a range of plausible behavioural responses across a range of different scenarios. This analysis is generally done at the level of those affected, such as taxpayers, families or businesses, rather than at the aggregate level. In the case of a policy proposal that increases a particular tax, for instance, this analysis may reveal that those affected can easily find ways to avoid the tax increase. In other cases, this type of analysis may reveal that a particular behavioural response would not have a material budget impact relative to the overall impact of the proposal.

4.2 We consult with experts to test and complement our thinking

Expert advice is particularly useful when considering behavioural responses to new or novel proposals and to test our thinking. The experts we reach out to include people in government departments, business or academia that specialise in particular policy areas. In many cases these experts may have independently considered the policy proposals that we are analysing, or can otherwise bring their specific experience to explore the potential consequences of a proposed policy. We have a panel of advisors who have expertise across a broad range of areas and are available for consultation when the need arises. On occasions, the expert panel members refer us to an alternative expert with the right knowledge.

4.3 We consult across the OECD network of Parliamentary Budget Officials and Independent Fiscal Institutions

There are a range of organisations across Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries that cost policy proposals, including government departments and independent fiscal authorities. All of these organisations have to make assumptions about behavioural responses. While the policy context may vary considerably across countries, other country experiences can inform our thinking, particularly when a policy proposal has similarities to a policy that has been implemented in another country. The OECD Network of Parliamentary Budget Officials and Independent Fiscal Institutions enables us to tap into the work of other parliaments, PBOs and fiscal councils8. This network gives us an opportunity to discuss budgeting issues, share practical experiences on working methods, identify good practices and contribute to standard setting.

4.4 We form our own expert judgement

Ultimately, all assumptions around behavioural responses require a degree of expert judgement. Even when we have collected a strong evidence base to inform a particular assumption, such evidence rarely relates to exactly the same policy in the same context. Box 3 provides an example of where we developed a behavioural response that drew upon empirical literature, involved our own empirical analysis of historical data, and was complemented by an analysis of possible scenarios, expert consultation and, finally, our own expert judgement.

Box 3: Case study – Negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount

The Australian Labor Party and the Australian Greens both made election commitments in 2019 that involved the removal of negative gearing and changes to the capital gains tax discount (see Negative gearing and capital gains tax (CGT) reform PER414, and Phase out the current tax treatment of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount PER660). Each of the proposals would only apply to assets purchased after the policy start date, providing a strong incentive for investors to bring forward their asset purchases to before this date. This would ensure these investors would continue to access negative gearing and the existing capital gains tax discount on these assets.

There is international empirical evidence to suggest that some individuals bring forward transactions to reduce the impact of a future property tax increase.9 To back up this evidence, we conducted our own empirical research on the introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) on 1 July 2000, which increased the cost of new housing. By analysing new housing purchases in the years before and after the introduction of the GST, we estimated that approximately 10 per cent of purchases that would have been made in the 12 months following the GST introduction, and a further 5 per cent of purchases that would have been made between 12 and 24 months after the GST introduction, were brought forward to before 1 July 2000 in order to avoid the GST.

The empirical evidence, both domestic and international, was based on relatively small increases in the cost of housing. We looked at a number of scenarios for property investors under both proposals and found that, for many investors, the proposals would have a larger impact on the cost of an investment property10 than the introduction of the GST had for new properties. After consulting with an outside expert, we applied our expert judgement and assumed that both proposals would induce a more significant behavioural response. Specifically, we assumed that 20 per cent of purchases that would have been made in the 12 months after the start date, and 10 per cent of purchases that would have been made between 12 and 24 months after the start date would be brought forward to before the start date.

5 Ensuring transparency

The PBO is committed to transparency around behavioural assumptions. This helps parliamentarians understand how individuals and businesses affected by their policy proposals are likely to respond, and provides assurance to the wider public that we think carefully about the assumptions we make.

5.1 We include details of our behavioural assumptions in our costings advice to parliamentarians

Our advice to a parliamentarian about their policy proposal details all of the key assumptions we have made to estimate the cost of the policy proposal, including behavioural assumptions. As a general rule, this specifically includes the assumed magnitude of the behavioural response, with a discussion about some of the ways those affected may respond.

We also note in our costings advice the degree of uncertainty in the estimated budget impact associated with our behavioural assumptions. The extent of this uncertainty depends upon the sensitivity of the estimates to particular behavioural responses, the strength and reliability of the underlying evidence, and the degree of confidence we have in applying our expert judgement.

5.2 We undertake sensitivity analysis for highly uncertain assumptions

In some cases, the estimated budget impact of a proposal will be very sensitive to a highly uncertain behavioural assumption. In our costings advice, we typically quantify the impact that such a behavioural assumption has on the financial implications of a policy proposal, both in dollar terms and as a percentage of the overall budget impact. In the interests of transparency, we often provide additional sensitivity analysis that states how the estimated financial impact of a policy proposal would change with a smaller or a larger assumed behavioural response.

5.3 The attached list of behavioural assumptions is provided in the interests of transparency

Our online behavioural assumptions glossary provides a consolidated list of the behavioural assumptions that have been used in a wide range of published PBO costings during 2019, including the election commitment costings in the 2019 Post election report of election commitments. These cover a broad range of policy areas, including personal income tax, business tax, superannuation, transfer payments, immigration, child care, education, and health.

Each example a link to at least one published costing. This provides the details of the policy specification that is relevant to the particular behavioural assumption, along with the other assumptions, methodology, and data that were used to undertake the costing, and a discussion of the uncertainties associated with the costing. While some assumptions are common to a number of policy proposals, some are specific to a particular policy specification. The behavioural assumptions used in our future costings of similar policy proposals may differ from those in the glossary, particularly if there are differences in the details of the proposed policy specifications.

Behavioural assumptions are regularly reviewed and updated when new evidence comes to light. We welcome scrutiny of these assumptions and invite comments on them. Supporting empirical evidence for these or alternative behavioural assumptions would be particularly welcome. Please provide any feedback to feedback@pbo.gov.au.

References

Klemm, A., Liu, L., Mylonas, V. and Wingender, P., 2018, Are Elasticities of Taxable Income Rising?, International Monetary Fund.

Office for Budget Responsibility, 2016, Working paper No. 10, Forestalling ahead of property tax changes.

Parliamentary Budget Office, 2019, 2019 Post-election report of election commitments.

PBO Information paper no. 02/2017, What is a Parliamentary Budget Office costing?

PBO Information paper no. 03/2017, Including broader economic effects in policy costings.

Footnotes

- See What is a Parliamentary Budget Office costing?

- See Including broader economic effects in policy costings.

- Parliamentary Budget Office, 2019, 2019 Post-election report of election commitments.

- In economics, an elasticity is a parameter that captures what the percentage change in one variable would be for a given percentage change in another variable. For example, a price elasticity measures the percentage change in consumption of a particular good or service that is expected to result from a one per cent increase or decrease in the price. Elasticities are estimated using econometric studies.

- See, for instance, Klemm, A., Liu, L., Mylonas, V. and Wingender, P., 2018, Are Elasticities of Taxable Income Rising?, International Monetary Fund. Many of the estimates in the empirical literature capture both a tax-planning response and a labour-supply response.

- Where a policy proposal would make a more substantial change to marginal tax rates (eg increasing the highest marginal tax rate by 10 percentage points), or would target very high income earners (eg those with taxable incomes above $1,000,000), these elasticities may no longer be appropriate. In such cases we apply our judgement and may deviate from the taxable income elasticities that are estimated from recent experiences for the whole population.

- For more information on the network, see

http://www.oecd.org/governance/budgeting/oecdnetworkofparliamentarybudg…. - See, for instance, Office for Budget Responsibility, 2016, Working paper No. 10, Forestalling ahead of property tax changes.

- The additional costs were measured as the denied deductions and the increased tax upon the sale of the property, expressed in today’s dollars.