Overview

This Budget Explainer updates our 2021 report, The Contingency Reserve, to include the impact of COVID-19, which led to a sharp increase in the reserve to a record level of $57 billion (2.7% of GDP) in 2020-21. The explainer outlines what influences the Contingency Reserve’s size and provides insights into an otherwise opaque component of the budget papers.

The Contingency Reserve is an allowance within the government’s budget estimate forecasts for items that either cannot or should not be allocated to specific programs at the time of publication. It is a tool to account for uncertainty and improves the accuracy of the aggregate budget estimates. This in turn supports the goals of responsible fiscal policy and sustainable economic development.

At any time, the Contingency Reserve includes a variety of provisions. However, the two main provisions are the Conservative Bias Allowance (CBA), which is an allowance for the historical tendency for expense estimates to be under-forecast; and Decisions Taken But Not Yet Announced (DTBNYA), which is the value of policy decisions that have not yet been disclosed, along with policies that have been announced but whose costs cannot be published.

The CBA is generally the largest component of the Contingency Reserve and was introduced to take account of an observed tendency for budgets to underestimate future expenses, even after allowing for changes in policy and economic forecasts. It is designed to account for all the changes in estimates of expenses from ‘program specific’ factors. The provision scales up over the forward estimates to reflect greater uncertainty into the future and is unwound at subsequent updates as uncertainty reduces. PBO analysis of the past 30 years shows the CBA generally improves the accuracy of budget estimates in practice.

DTBNYA covers expenditure and non-tax revenue decisions that have been included in the budget aggregates but not yet announced, as well as policies that have been announced but whose costs cannot be disclosed. DTBNYA amounts have been published consistently since 2004‑05, with their total size increasing significantly over the years since then. Policies may not be announced, or their amounts left undisclosed, for a variety of reasons.

Whilst the use of the Contingency Reserve does improve the accuracy of aggregate budget estimates, it also reduces transparency. As an aggregate provision, it is not always possible to see the annual funding profile for important expenditure and non-tax revenue decisions.

Introduction

This Budget Explainer examines the definition and use of the Contingency Reserve in the Australian Government budget. It outlines what influences the Contingency Reserve’s size and provides insights into an otherwise opaque component of the budget papers.

This Explainer is part of a series that seeks to improve understanding of key parts of the budget that are not well understood. Other topics include indexation and its impact on the budget, and various taxation topics including superannuation, fuel excise and bracket creep.

What is the Contingency Reserve?

The Contingency Reserve is an allowance within the Commonwealth budget for events that the government reasonably expects to eventuate but has not allocated to specific programs or detail. By including these items on an aggregate basis, rather than omitting them, the Contingency Reserve improves the accuracy of aggregate budget estimates at the time of their publication.

Overall accuracy in the aggregate budget estimates is an important component of responsible fiscal management. Including items within the Contingency Reserve is a key accountability provision and supports the efficient allocation of resources and management of risks. As funding needs to be appropriated at fixed times, it is important that the estimate reflects the expected appropriation needed to meet the Government’s policy goals.

Although its name may imply that the Contingency Reserve is a stock of funds, which would be expected to appear on the government’s balance sheet together with cash deposits and other assets, it is actually a flow on the expense side of the government’s operating and cash flow statements.

Since the Contingency Reserve was introduced in 1987, it has included a variety of items which generally fall within the following groupings:

-

The Conservative Bias Allowance (CBA), which makes provision for the historical tendency for the estimates of expenses for existing government policy to be under-forecast, and hence revised upwards later. The CBA is discussed further in this explainer.

-

Expense and non-tax revenue policy decisions that were not announced in the fiscal update. These are classified as Decisions Taken But Not Yet Announced (DTBNYA). The Contingency Reserve contains the cumulative impact of funding for outstanding and new DTBNYA. These policies are usually announced and published in a future fiscal update.1 Budget aggregates can also include DTBNYA that relate to taxation, but these are included elsewhere in the budget in the tax revenue estimates, as opposed to the Contingency Reserve. DTBNYA are explored in more detail later in this explainer.

-

Items that are too sensitive to be disclosed separately, such as those that are commercial‑in‑confidence or affect national security. In some cases, a description of the item is disclosed in the fiscal update while the funding allocated to it is not. In other cases, no information is disclosed. The 2021-22 Budget, for instance, included a provision for the manufacturing of messenger RNA vaccines in Australia, but funding was not disclosed as the exact price negotiated with pharmaceutical companies was commercial-in-confidence.2

-

An aggregate provision for underspends in the budget year, reflecting the tendency for budgeted expenses for some entities or functions not to be met.

-

Information that is received too late during the preparation of the fiscal update to be allocated to estimates of individual items, such as policy decisions or changes to the expected economic outlook.3 The information is instead included at the aggregate level in the Contingency Reserve and allocated to the individual program estimate at the next update.

-

Provisions for items that have a significant amount of uncertainty at the time of publication, such as programs still under negotiation with state and territory governments, or for the establishment of new agencies whose legislation has not yet passed Parliament.

Figure 1 below shows how the components of the Contingency Reserve and DTBNYA are related, highlighting that the Contingency Reserve includes more than just DTBNYA, but does not include tax revenue DTBNYAs. These measures are instead incorporated into the revenue forecasts in Budget Paper 1.

Figure 1. Contingency Reserve and DTBNYA components

The description of the Contingency Reserve in a fiscal update will occasionally provide information on other specific items included. An example is the 2009-10 Budget, where the Contingency Reserve amounts were relatively large, and included: provisions for future equity investments in the National Broadband Network (subject to an implementation study); estimates of revenue and expenses related to the then proposed Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (where the timing was dependent on the actions of other major economies); and provisions for future increases in Australia’s Official Development Assistance yet to be allocated to specific aid programs.4 See Appendix A for a complete list of all items that have been included in the description of the Contingency Reserve throughout history.

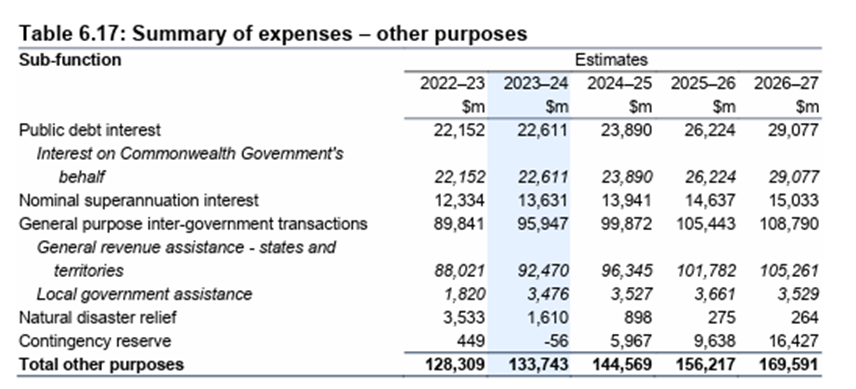

Information on the Contingency Reserve is currently presented in Budget Paper No 1, in the expenses and net capital investment statement.5 Table 1 reproduces the information from the 2023-24 Budget.

Table 1: Other purposes function: the Contingency Reserve

Source: 2023-24 Budget, Budget Paper No 1, p 227

In general, this table shows the total provisions under the Contingency Reserve and the accompanying text covers the amount allocated to the CBA. Other provisions within the Contingency Reserve are rarely explicitly identified or quantified, and so can only be examined on an aggregate basis.6 The Contingency Reserve in each year also tends to become smaller as it becomes closer to the current period as highlighted in in Box 1.7

Box 1: Contingency Reserve amounts tend to reduce over time

Amounts allocated to the Contingency Reserve in a given financial year tend to decrease in subsequent budgets. This is because provisions are drawn down as the expected events occur or are otherwise resolved. For example, decisions are announced, which moves amounts out of the Contingency Reserve to be allocated to the relevant budget provision. As uncertainty about outcomes in the estimated financial year decreases as the end of the year approaches, the CBA also reduces.

As the Contingency Reserve only includes provisions for the future, it is not included in the Final Budget Outcome, effectively reducing the value to zero so there are no historical ‘actual’ amounts.

For example, at the 2008-09 Budget, the last year of the forward estimates was 2011-12, which included an amount in the Contingency Reserve of $12 billion. At the following Budget this 2011-12 amount was reduced to $7 billion, and then to $3 billion at the 2010 11 Budget.

The Contingency Reserve is a buffer to reflect estimate uncertainty and is not a general reserve of money that can be used to fund future policies.8 That is, the Contingency Reserve cannot include money to be simply put away ‘for a rainy day’ or for aspirational policy goals. If it operated like this, the budget estimates would not be an accurate reflection of total expected spending and revenue, and policies would more regularly be announced without changing the baseline totals.

Other countries also have contingency reserves which differ in their disclosed use and size. For example, the government of South Africa’s budget Contingency Reserve provides for unforeseen and unavoidable expenditure, such as natural disasters, while Bosnia’s Contingency Reserve provides for shortfalls in revenue.9 Other functions of contingency reserves may include financing of foreign investment projects and unfunded mandates, used as loan guarantees, support for infrastructure spending, and other appropriations. The size of contingency reserves also varies across countries, ranging from less than 1% (the United Kingdom, the Netherlands) to up to 3% (Sweden) of total government expenditure.10 At the 2023-24 Budget, the size of Australia’s Contingency Reserve expenditure was approximately 1% of total government expenditure.

History of the Contingency Reserve

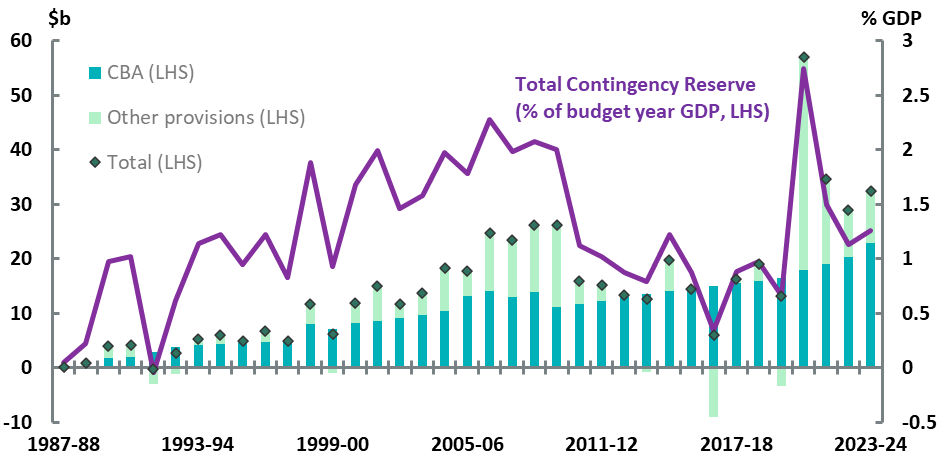

The Contingency Reserve has been included in budget forecasts since the 1987-88 Budget.11,12 It was included to provide more accurate estimates of future outlays, as this was the first budget to include estimates beyond the next year to include the second, third and fourth year (the ‘forward estimates'). Figure 2 shows the breakdown between the CBA, and other provisions included in the Contingency Reserve over time. The CBA is typically the largest component of the Contingency Reserve, and other provisions generally include the cumulative amount of all DTBNYA measures from previous budget updates that have not yet been allocated and still have an impact on the budget estimates. The Contingency Reserve has almost always increased expense estimates.

Figure 2: Disaggregation of the Contingency Reserve, by budget

Source: Commonwealth budgets and PBO analysis.

Note: Impact is presented on an expense basis and is aggregated over the forward estimates for each budget. For example, '2011-12' refers to the total amounts allocated to the Contingency Reserve at the 2011-12 Budget, for the budget year and forward estimates years of 2011-12 to 2014-15. Provisions that would increase expenses or decrease revenue are recorded as positive, while provisions that would decrease expenses or increase revenue are reported as negative. CBA amounts are PBO calculations, which may differ very slightly from those published in budgets.

What is the Conservative Bias Allowance?

The CBA is an allowance for the historical tendency to underestimate expenses over the forward estimates. The amount of this provision is calculated as a certain percentage of total expenses, excluding GST payments to the states and territories (the ‘CBA percentage’). The current CBA percentage is zero in the Budget year, 0.5% in the first year of the forward estimates, 1% in the second year, and 2% in the final year.13 An example of a calculation of the CBA is shown in Box 2.14

Box 2: Conservative Bias Allowance calculation.

Consider the estimates for the year 2019-20 in the 2018-19 Budget. Total expenses were estimated to be $504,171 million and GST payments to the states were estimated to be $69,790 million. The CBA percentage for this year was 0.5 per cent, so the total amount provisioned in the CBA may be estimated as:

0.5% × (504,171 – 69,790) =

$2,172 million.

The CBA does not account for all possible reasons why expense outcomes may differ from their budgeted forecasts. The budget specifies the following five reasons why forecasts for expenses vary from one update to the next:

- new policy decisions

- revisions to economic parameters, such as economic growth, prices and unemployment

- revisions to other parameters, specific to particular programs

- changes to the amount of interest the government is expected to pay on its borrowings

- other variations not captured otherwise.

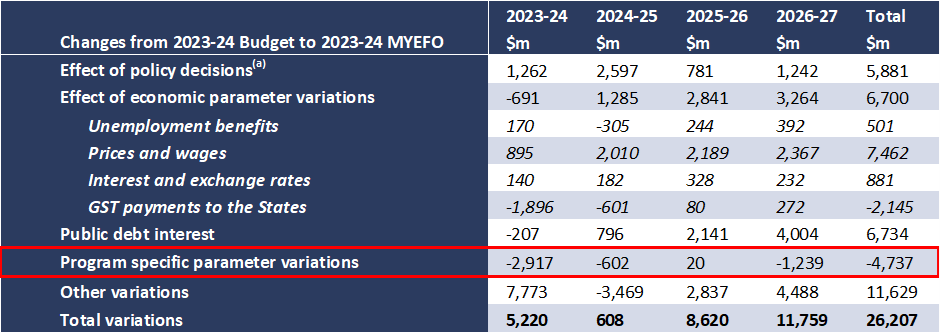

The CBA percentage is intended to compensate for only the third of these factors, referred to in the budget as 'program specific parameter variations'.15 Box 3 provides an example to clarify the differences between these types of variations.

Box 3: Sources of variations in forecasts for expenses

Expenses estimate forecasts are revised between fiscal updates for two key reasons, to take account of either policy decisions or parameter variations.

A policy decision would be if, for example, the Government decided to change the payment rate of the Age Pension, this change to previously forecast Age Pension spending would be captured under ‘effect of policy decisions.’

Parameter variations come in two types: economic and program specific:

- economic: if the Consumer Price Index (CPI) forecast was revised upwards, then the payment rate for the Age Pension, partly indexed to the CPI, would also be expected to increase. This increase to previously forecast Age Pension spending would fall under ‘total economic parameter variations.’

- program specific: if the expected proportion of Age Pension recipients who are single was revised upwards due to new demographic information, more people would be expected to receive a higher rate of payment. This increase to Age Pension forecasts would be captured under ‘program specific parameter variations,’ as the proportion would be estimated specifically for Age Pension forecasts, rather than as part of the general economic parameters for the Budget.

The CBA percentage is based on recent historical trends in revisions to forecasts of expenses and is therefore revised from time to time. Appendix B shows the history of the CBA percentage.

Total program specific parameter variations are published in the budget papers. Table 1 reproduces a subsection of the expense ‘reconciliation’ table from the 2023-24 Budget, which explains the changes in expenses between one budget update to the next.

Table 1: Sample reconciliation of expense estimates

Source: 2023-24 MYEFO, p 83.

Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. Program specific parameter variations are highlighted for emphasis. The effect of policy decisions excludes secondary impacts on public debt interest and offsets from the Contingency Reserve for decisions taken.

The source of 'program specific' variations is primarily 'demand-driven' programs–that is, programs such as the Age Pension where the required amount of funding is not capped, but depends on the number of users. Estimates of future spending are therefore more uncertain than for programs with capped funding.16,17 As a given year moves through the forward estimates in later updates, the amount of uncertainty in aggregate spending estimates decreases and this is reflected in a decrease to the amount allocated to the CBA. These decreases are referred to as 'drawdowns' and are explored in more detail in Box 4.

Box 4: Drawdowns of the CBA

The 2022-23 October Budget included a CBA for the 2023-24 year of $1.4 billion. The 2023-24 Budget referred to a ‘drawdown’ of the 2023-24 CBA of $1.4 billion, reducing the amount to zero as the CBA for the budget year is equal to 0% of expenses, reflecting the fact that the total expenses estimated for the budget year are usually relatively close to the final outcome. This language can be confusing because the CBA does not represent an actual fund and a ‘drawdown’ does not represent a saving to the budget.

Does the Conservative Bias Allowance improve the accuracy of budget estimates?

Medium term expenditure frameworks (MTEF)18 aim to overcome the limitations of the annual budget cycle by adopting a medium-term perspective for achieving government fiscal objectives. They generally span the budget year and at least 3 years beyond. In Australia, this 4 year period is known as the forward estimates. MTEF's improve budget formulation by framing expenditure plans on the basis of existing resources and link the annual budget to multi-year policies. They also increase budget stability be decreasing uncertainty in expenditure flows. To be effective, the expenditure estimates need to be based on high quality projections, which facilitates planning and fiscal discipline, and ultimately efficient resource allocation and sustainable economic growth.

The CBA is a key tool to address uncertainty to support sound budget estimates over the forward estimates. The PBO has reviewed the past 30 years of budget program variations. This analysis indicates that, on average, there is a historical tendency to underestimate aggregate expenses and that the CBA does work as intended to improve the accuracy of aggregate expense estimates.

- While some individual years vary significantly, the long run average of the sum of program specific variations is approximately 2%, the same size as the current CBA.

- The positive long-run average of program specific variations confirms that there is a historical tendency to underestimate aggregate expenses.

- The consistency between the size of this tendency and the CBA percentage in this high-level test means that the CBA does improve the accuracy of aggregate expense estimates.

Since its introduction, the size of the CBA has varied. Sometimes this reflects that the relevant annual budget was part-way through a year (for example the 2022-23 October Budget), or different views about how much inherent uncertainty there was in the estimates. The current settings for full year budgets have applied since 2009-10.

Appendix B provides more detailed analysis of the CBA, including comparisons of program specific variations for each year of the forward estimates, and a complete history of the CBA.

What are 'Decisions Taken But Not Yet Announced'?

Over time, the Government has increasingly made decisions with financial impacts outside of the annual budget process (see Figure 3). Some of these may be announced ahead of a fiscal update, but some may not. Most fiscal updates include some new policies, the details and costs of which have been calculated but not announced. The fiscal impacts of all these unannounced policies are aggregated and presented as a single line DTBNYA in Budget Paper No 2, in the tables showing the receipts, payments and capital measures.19

The total published DTBNYA amount includes new policies not yet announced as well as policies that have been announced but whose costs cannot be published. In the latter case, short summaries of policies, known as ‘measure descriptions’ are still published for these policies, but the amounts are replaced by ‘nfp’ (not for publication).

The financial impacts of unannounced and not for publication policies are generally included in the Contingency Reserve. An important exception to this is tax policies, where the impacts are explicitly incorporated into the estimates for the relevant taxes, rather than within the Contingency Reserve.

Both unannounced tax and non-tax revenue policies are included in the aggregate figure for revenue DTBNYA in Budget Paper No 2, but only the unannounced non-tax revenue policies are included in the Contingency Reserve.

There are several reasons why policies may not be announced, or amounts cannot be published.

- Information may be commercial-in-confidence, or its disclosure could prejudice national security. For example, the cost of the 2023-24 Budget measure, Energy Price Relief Plan, was listed as ‘not for publication (nfp) due to commercial sensitivities.’20 Similarly, the fiscal impact of new listings to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme is usually reported as nfp.21

- Some policies may have been finalised very late in the budget process, and it is not possible to allocate the financial impact in detail.

The government, who choose the timing of their policy announcements, may include some policies within DTBNYA in order to announce them later.

If a subsequent fiscal update announces a policy which has previously been included within DTBNYA then the measure tables show no impact on budget estimates, because the budget estimates have already included the impact at the aggregate level. This is often reflected with a note such as ‘Funding for this measure has already been provided for by the Government.’ The description of the policy in Budget Paper No 2 may also include the cost of the policy which has already been accounted for.22 However, it usually does not include the detailed funding profile for the decision and in some cases the funding profile is never disclosed.23

An example of a measure previously accounted for as a DTBNYA is shown in Box 5.

Box 5: Example of a policy previously included as a DTBNYA

This is a simple example of the publication of a policy which was announced in one update (the 2019 20 Budget) but whose financial impact had already been included in a previous update. The cost of the policy for this update is zero, but the description reveals the full cost of the policy ($5.0 million), which was already incorporated in a previous budget update.

Source: 2019-20 Budget, Budget Paper No 2, page 106

When a previously unannounced policy is subsequently announced, the financial impact of that policy is moved from the Contingency Reserve to the relevant program or non-tax revenue item, unless it is a tax revenue item in which case it was already included in tax estimates. Policies included in DTBNYA are not necessarily announced by the next fiscal update, so unannounced policies may remain within the Contingency Reserve for multiple updates.

The DTBNYA lines in the tables in Budget Paper No 2 include only new decisions since the last update, but the cumulative impact of all these policies which remain unannounced is in the remaining aggregate provisions of the Contingency Reserve.24 This means that the Contingency Reserve may include many unannounced policies, from multiple updates, at one time.25

While measures under DTBNYA can be classified as a revenue, expense, or capital, the expenses DTBNYA is usually larger than the revenue DTBNYA, with an average size of $400 million for expenses and $150 million for revenue between the 2003-04 MYEFO and 2023-24 MYEFO.26

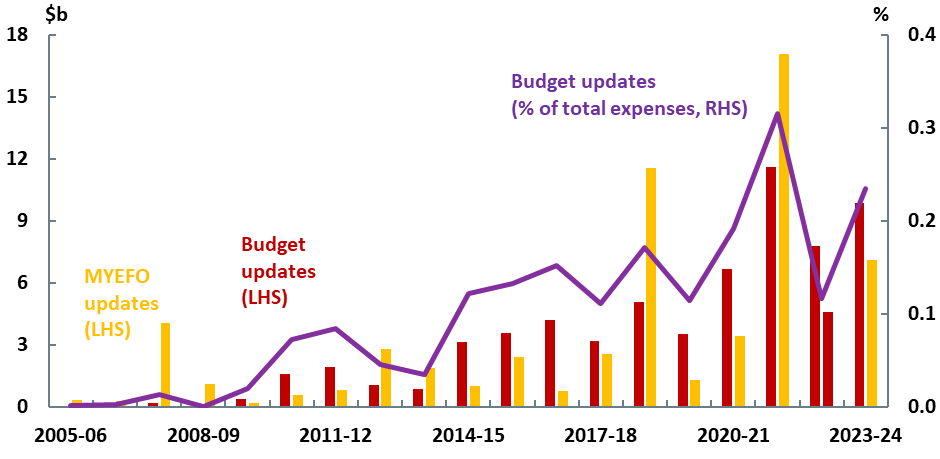

How have Decisions Taken But Not Yet Announced changed over time?

Up until 2004-05, DTBNYA was rarely disclosed in the budget, and when it was disclosed, it was usually very small. Since then, the size of new DTBNYA has increased significantly, both in absolute terms and relative to the rest of the budget, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Size of new DTBNYA over the forward estimates at each budget update

Source: Commonwealth budgets and PBO analysis.

Note: Values for both DTBNYA and total expenses are the total impact over the forward estimates for a given budget update. DTBNYA only includes new policies at each update, as included in Budget Paper 2, and not the total cumulative impact of all unannounced policies.

Appendix C provides more detail on significant DTBNYA, with implications of more than at least $1 billion in a single year. While there appears to be long term rise in the size of the provision, the most material instances seem to be related to unique events, such as COVID-19 or significant infrastructure decisions.

Provisions for DTBNYA are usually unwound ahead of a general election and reported in the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO).27 For example, the April 2022 PEFO noted that the total impact of new policy decisions on the underlying cash balance was ‘partially offset by the reversal of a number of decisions previously taken but not yet announced ($364.6 million over the 4 years to 2025-26)’.28

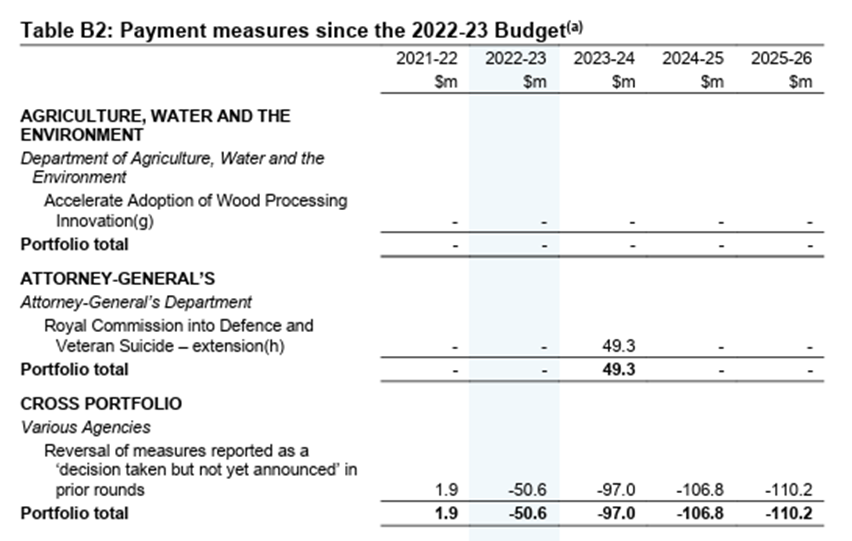

Table 3 shows the reversal referred to above. It provides information on the relevant portfolio items previously captured in a DTBNYA provision, as well as the aggregate provision. However, there is limited detail on the funding profile for the individual measures.

Table 3: Illustration of DTBNYA reversal in the 2022 PEFO

(a) A minus sign before an estimate indicates a reduction in payments, no sign before an estimate indicates increased payments.

Source: 2022 PEFO, p. 25

More broadly, the update to the budget estimates included in the PEFO usually includes adjustments to the Contingency Reserve to reflect the unwinding of uncertainty. In 2022, the PEFO explains how the Contingency Reserve was adjusted by $339.4 million over 4 years to 2025-26 to reflect:

- The partial drawdown of the budget provision for potential costs of the long-term response to the February-March 2022 floods in parts of NSW and Queensland

- The removal of DTBNYA from the budget or prior rounds, which have now been reflected against entity estimates. These movements do not have any impact on the underlying cash balance as funding for DTBNYA items have already been reflected in the estimates in the previous budget rounds.

- The reversal of DTBNYA from the budget or prior rounds, the value of which are included in Appendix B (reproduced in the extract of Table B2 in Table 3).28

Concluding comments

The Contingency Reserve provision seeks to improve the reliability of the budget forward estimates by taking account of some known uncertainty risks related to program specific issues. The key ones being the tendency to underestimate future outlays (the CBA) and DTBNYA.

The benefit in improving the estimates at an aggregate level is somewhat offset by the loss of fiscal transparency at a more detailed level, especially the funding profile for policy decisions that are eventually announced.

For more insights on the impact of another significant variation to the budget estimates – changes in prices and how they flow through to the budget via indexation, see our publications Indexation & the budget – an introduction and Indexation & the budget – long-term impacts.

Appendix

Appendix A: Components listed in the Contingency Reserve at each budget

The list below includes all the items that have been specifically mentioned as being in the Contingency Reserve in a budget. It does not include items revealed to be in the Contingency Reserve outside of budget updates, for example in media releases or during Senate Estimates. Items are presented in chronological order of their appearance. Unless otherwise stated, items have appeared in multiple updates. Some of these items, such as asset sale related expenses, have been moved in and out of the Contingency Reserve at various points.

- Wage and salary increases for departments and Commonwealth statutory authorities.

- Salaries costs of former Public Service Board staff to be redeployed as a result of the restructuring of that organisation (1987-88 Budget only).

- Carryover of unspent administrative expenses appropriations.

- Savings resulting from the streamlining of the travel arrangements for the Public Service (1987‑88 Budget only).

- Possible increased payments by departments and budget financed Commonwealth statutory authorities to superannuation schemes for employees who are not members of the Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme under the guidelines of the National Wage Case (1988‑89 Budget only).

- Expected underspends by departments of amounts appropriated to them to pay for design and construction services provided by the Department of Administrative Services.

- Property expenses, including medium and minor works, new leases and fitout and rent revisions, which relate to the delivery of existing programs.

- The Conservative Bias Allowance.

- Expected savings from maintaining the efficiency dividend on departmental running costs.

- Parameter revisions received late in the budget process.

- Payment of customs duty on imports by Commonwealth departments (1990-91 Budget only).

- A limited number of possible net additions to outlays reflecting extensions of existing programs.

- Additional supplementation for the wage components of some programs this year, predominantly in the health and education areas.

- Commercial-in-confidence items that cannot be disclosed separately.

- Possible inaccuracies in the year just completed, due to the timing of the release of the Budget.

- Adjustment of running costs for the outcome of the administrative expenses deflator.

- Impact of changed arrangements for the management of agency property costs (1994‑95 Budget only).

- Carryovers for Defence relating to potential contract delays (1994-95 Budget only).

- The effect of an initiative to improve the management of cash between the Commonwealth, its statutory authorities and the States (1995-96 Budget only).

- The avoidable direct costs of the sale of Telstra, and the environment package which are contingent on the approval of the Telstra (Dilution of Public Ownership) Bill 1996 (1996‑97 Budget only).

- Maintaining pensions at 25% of total male Average Weekly Earnings.

- Established tendency for estimates of some programs to be overstated in the budget year.

- Funding for the proposed Federation Fund Trust Account.

- Increased rate of the Superannuation Guarantee Charge (1998-99 Budget only).

- Difference between proposed Australian Health Care Agreements being negotiated with States and Territories and the amounts in the forward estimates (1998-99 Budget only).

- National security-in-confidence items that cannot be disclosed separately.

- Minor decisions made late in the Budget process.

- Government’s decision to extend the operation of the Natural Heritage Trust.

- Expected changes to funding for the Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs and Indigenous Affairs as a result of a review yet to be conducted (2003-04 Budget only).

- Financial impact of health insurance premium growth on the Private Health Insurance Rebate.

- Impact of foreign exchange rate movements (2003-04 Budget only).

- Asset sale related expenses.

- Provision for events and pressures that are reasonably expected to affect the budget estimates.

- Continuation of the National Action Plan on Salinity and Water Quality (2006-07 Budget only).

- The difference between the amount of Official Development Assistance already committed and the government’s target levels.

- Ongoing costs associated with the Northern Territory Emergency Response (2008‑09 Budget only).

- Establishment of the National Broadband Network (2008-09 Budget only).

- Anticipated expenditure from the Building Australia Fund, Health and Hospitals Fund and the Education Investment Fund (2008-09 Budget only).

- Continuation of drought relief spending (2009-10 Budget only).

- Updated estimates of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (2009-10 Budget only) – these provisions were then explicitly removed in the 2010-11 Budget due to a government decision to not legislate this scheme until after the end of the Kyoto Protocol.

- Future equity investments into the National Broadband Network.

- The second tranche of the Nation Building program (2011-12 Budget only).

- Election commitments made at the 2010-11 MYEFO, which were then removed at the 2011‑12 Budget.

- The Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory package which was still under negotiation with the Northern Territory government at the time of publication (2012-13 Budget only).

- Commitment to pay the Commonwealth’s share of costs in response to the pay equity claim on behalf of certain workers in the Social and Community Services sector (2012-13 Budget only).

- Paid Parental Leave Scheme (2014-15 Budget only).

- Company tax rate reduction (2014-15 Budget only).

- Programmes that are yet to be renegotiated with State and Territory governments.

- Decisions taken but not yet announced by the government.

- Continuation of some expiring National Partnerships and possible by-election and redistribution costs for the Australian Electoral Commission.

- Funding for Investing in ChildCare – ICT system, Better Management of Biosecurity Risks – advanced analytical capability, Public Sector Transformation and the Efficiency Dividend and New Veteran Public Hospital Pricing Agreement (2016-17 Budget only).

- Increases in new medicine listings (2018-19 Budget only).

- Funding for the Indigenous Recognition Referendum and the Commonwealth Integrity Commission.

- Funding for the Future Drought Fund – establishment and Establish the Emergency Response Fund (2019‑20 Budget only).

- Provisions for costs associated with flood events.

- Provision for the replacement of the Australian Electoral Commission’s election and roll management systems as part of tranche 2 of their ICT modernisation program (2022-23 March Budget only).

- Implementation of election commitments published in the Plan for a Better Future (2022-23 October Budget only).

- Funding to support an increase to award wages resulting from aged care work value case being determined by the Fair Work Commission.

- Measures that require legislation to be implemented, including the establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Commission and the Housing Australia Future Fund (2022-23 October Budget only).

- Provisions for measures Savings from External Labour, and Savings from Advertising, Travel and Legal Expenses (2022-23 October Budget only).

- Increased Defence funding over the medium term to implement the Defence Strategic Review (2023-24 Budget only).

Appendix B: History and effectiveness of the Conservative Bias Allowance

History of the Conservative Bias Allowance

In the 1987-88 Budget, the Commonwealth Government introduced the Conservative Bias Allowance (CBA) to improve the accuracy of expenses forecast over the forward estimates, by providing an allowance for potential variations in program estimates due to 'program specific’ factors.29 The CBA is not intended to capture variations in economic parameters (for example, changes in the Consumer Price Index) or policy decisions (for example, a measure to change the rate of the Age Pension). Program specific parameter variations may include, for example, an increase in the expected proportion of Age Pension recipients who are single, leading to higher average costs per recipient than estimated (see Box 3 of this explainer).

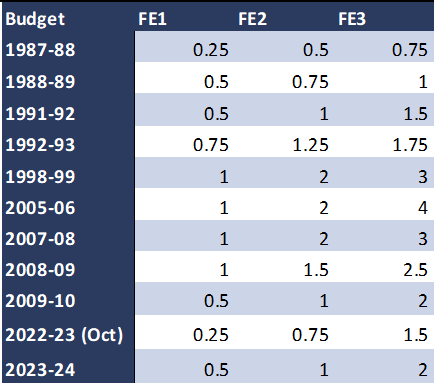

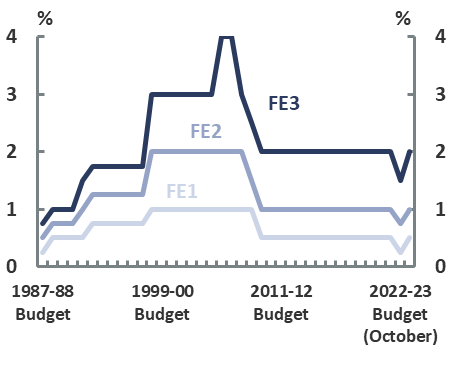

The CBA percentage is based on historical program specific parameter variations that occur as a given year progresses from being the third forward estimates year (FE3) to being the budget year. As these variations in expenses tend to be positive (upwards revisions) in the forward years, the CBA has been set at a positive rate throughout its history (Table B1 and Figure B1).

The CBA amount is calculated as a percentage of total general government expenses, less GST payments to states and territories. Over time the CBA percentage set at the annual budget has changed. It was initially set at 0.75% of outlays in FE3, gradually increased to 4% by the 2005-06 Budget, before being revised down to 2% by 2009-10. The CBA percentage has remained stable from 2009-10 to the time of publishing this explainer, except for a brief reduction at the 2022-23 October Budget, which reflected that the budget was released mid-way through the year.

|

Table B1: History of changes to the CBA |

Figure B1: CBA percentage, by budget |

|

|

Note: FE stands for forward estimates – FE1 is the first year of the forward estimates period, FE2 the second year and FE3 the third year.

Source: Commonwealth budgets.

The effectiveness of the Conservative Bias Allowance

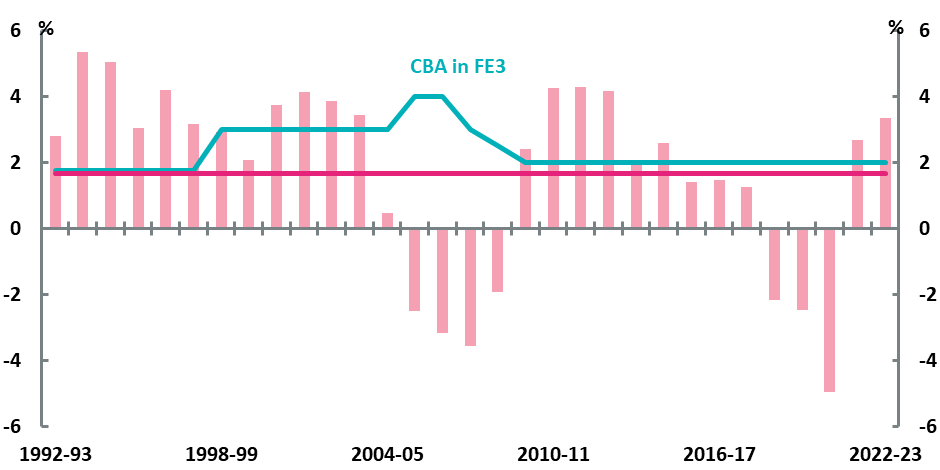

To investigate whether the CBA improves the accuracy of budget estimates, the CBA allocated in FE3 can be compared with the total reported program specific parameter variations for a given year over the period it is included in the budget, from when that year is FE3 to its final ‘outcome’.30 While these might not align for a given year, if the long-run average of program specific parameter variations is similar to the CBA percentage, then the CBA is improving the accuracy of estimates.31

For example, in the 2014-15 Budget, the year 2017-18 had a CBA of 2% of total expenses ($8.2 billion). For the CBA to exactly account for reported variations in program estimates, the sum of all the ‘program specific parameter variations’ for 2017-18, through each budget update from the 2014 15 MYEFO to the 2018-19 Budget, should equal $8.2 billion. However, the sum of these was $5.1 billion, or 1.2% of the original expenses estimate for 2017-18, suggesting that the CBA slightly overestimated expenses for this year.

Figure B2 compares the relationship between the CBA reported in FE3 and the total reported program specific parameter variations between FE3 and the budget year. Historically, there has been a tendency to revise expenses upwards, except between 2005-06 and 2008 09 and more recently from 2018-19 to 2021-22. This suggests that during periods of economic uncertainty, such as during the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, the upwards trend in expenditure revisions is reversed. However, overall the long run average of 2% is similar to the level factored into the CBA, confirming that the CBA accounts for the tendency of budgets to underestimate expenses.

Figure B2: Program specific parameter variations compared to the CBA percentage

Note: Amounts are expressed as a percentage of total government expenses minus GST payments to the states and territories. This includes all reconciliations in budget updates from 1993-94 onwards, except where reconciliations were not published such as at the 1999-00 Budget and the 2010 Pre-election fiscal outlook. The long-run average excludes variations from 2019-20 and onwards as they may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Commonwealth budgets and PBO analysis.

Appendix C: Examples of Decisions Taken But Not Yet Announced

To illustrate the varying uses, budget treatments and reporting for DTBNYA, this appendix discusses the largest historical cases. There are 12 budget updates which have included a DTBNYA of at least $1 billion in a single year, which are presented below in order of largest DTBNYA in a single year. Given the increase in DTBNYA in recent years, as well as the impacts of economic growth and inflation, these cases largely come from the last 10 years. These DTBNYA examples include expenses, which are budgeted through the Contingency Reserve, as well as revenue, of which tax measures are included in revenue forecasts as opposed to the Contingency Reserve. Some of these examples may include the financial impacts of measures that are not for publication, some of which are not held in the Contingency Reserve.

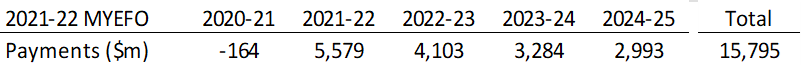

1. 2021-22 MYEFO32

The two largest DTBNYA amounts in a single year were both included in the 2021-22 MYEFO and represented a total of $5.6 billion of payments in 2021-22 and $4.1 billion of payments in 2022-23. These amounts, along with $3.3 billion in 2023-24 and $3 billion in 2024-25, totalled almost $16 billion over the forward estimates.

Released prior to the May 2022 election, these amounts included $4.3 billion for the national broadcasters, $3.7 billion towards a new National Skills Agreement, a $2 billion increase in funding for the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility, $1 billion for COVID-19 vaccines, $1 billion for university research commercialisation, as well as partial funding towards a $14.5 billion infrastructure package. It also included $1.2 billion in support for the Australian space industry, which was later reversed in the 2023-24 Budget. Typical of these cases, it is not possible to determine the exact funding profile of these measures, and it is unclear how much was included in the forward estimates or beyond.

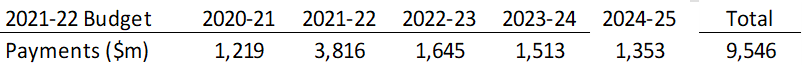

2. 2021-22 Budget33

The 2021-22 Budget included a DBTNYA of $3.8 billion for 2021-22, contributing to a total amount of almost $10 billion over the forward estimates.

While these amounts included several individual items, a significant component is likely to be related to COVID-19 vaccines and other medical goods.34 As these relate to commercial in confidence arrangements, the precise amounts provisioned for in the Budget were not made public. More details of some of these measures were included in the Budget, but the specific amounts allocated to each are not for publication.35 The subsequent 2021-22 MYEFO announced a $1.1 billion package for the Closing the Gap initiative, for which partial funding had been included as a DTBNYA at the 2021-22 Budget. It has also been confirmed that a provision of $600 million was included as a DTBNYA for a new power plant at Kurri Kurri.36

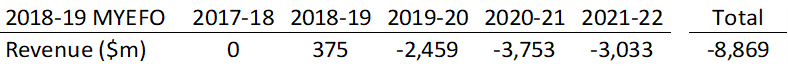

3. 2018-19 MYEFO37

The 2018-19 MYEFO also included a DTBNYA amount of $3.8 billion in 2020-21, this time for revenue. Most of this was due to an unannounced tax policy, and therefore did not affect the Contingency Reserve. It was instead explicitly factored into the tax forecasts at the 2018-19 MYEFO.

Careful readers of the MYEFO may have noticed that income tax withholding was revised down significantly, despite positive parameter and other variations, potentially indicating sizeable tax cuts being factored into the estimates.38 The following budget announced the government’s policy, Lower taxes for hard-working Australians, and confirmed that the MYEFO had included a ‘provision for the impact of this measure’ of a similar size to the DTBNYA. The impact of the announced policy at the 2019-20 Budget was therefore relatively small, since most of the policy had already been allowed for at the previous MYEFO.

Similar to the largest DTBNYA, at the 2021-22 MYEFO, this case was also at the MYEFO update immediately preceding a general election.

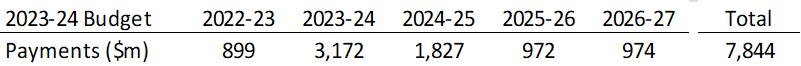

4. 2023-24 Budget39

The 2023-24 Budget included a DTBNYA of $3.2 billion in 2023-24, followed by another large DBTNYA of $1.8 billion in 2024-25, and a total of almost $8 billion over the forward estimates. These payments likely include measures not for publication due to commercial sensitivities, such as the ongoing COVID-19 response and commercial arrangements associated with the nuclear-powered submarine program.40 It also includes several unannounced measures such as programs to improve cancer outcomes and increased social security payments associated with an increase in Australia’s humanitarian intake.

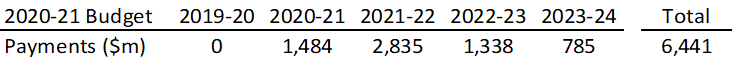

5. 2020-21 Budget41

The 2020-21 Budget, delayed five months due to the pandemic, also included a large DTBNYA peaking in 2021-22. This was likely for similar reasons to the 2021-22 Budget (see above).

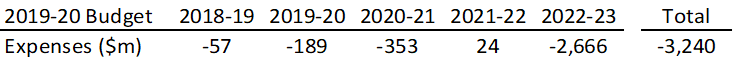

6. 2019-20 Budget42

The 2019-20 Budget, which led into the 2019-20 federal election, included a large negative DTBNYA in the final year of the forward estimates, following much smaller amounts for the preceding years.

The overall size of the Contingency Reserve suggests that the net impact of all the non CBA provisions was small. The 2019-20 Budget reported that the CBA explained all but $500 million of the Contingency Reserve for 2022-23.43

Some of this may be due to reversals of policies introduced but not announced at previous budget updates.44 In this case, DTBNYA amounts reducing expenses by $2.7 billion in 2022-23 could have been the reversal of previous measures which increased expenses. With 2022 23 being outside of the forward estimates before the 2019-20 Budget, the value of the previously unannounced decisions would be unknown.

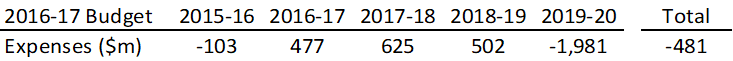

7. 2016-17 Budget45

Like the 2019-20 Budget, the 2016-17 Budget also included a reduction of expense estimates in DTBNYA in the final year of the forward estimates.46 Just as in the 2019-20 Budget, the value of the previously unannounced decisions that were reversed are unknown.

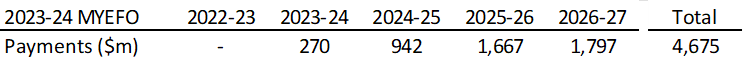

8. 2023-24 MYEFO47

The latest budget update includes two DTBNYA that total over $1 billion - $1.7 billion in 2025-26 and $1.8 billion in 2026-27. These amounts likely include several individual items.

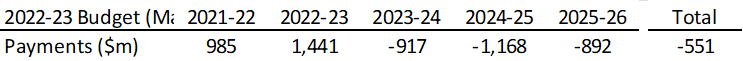

9. 2022-23 Budget (March)48

The 2022-23 March Budget included a $1.4 billion DTBNYA amount in 2022-23, followed by approximately $3 billion in reduced expense estimates over the forward estimates.

The 2022 PEFO revealed that many of these amounts were for decisions taken that were later reversed.

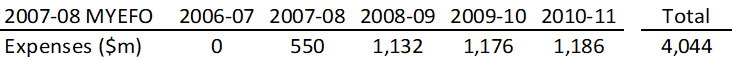

10. 2007-08 MYEFO49

A $1.2 billion amount for DTBNYA appeared in the 2007-08 MYEFO, which led into the 2007 federal election.

Unlike the cases for the 2016-17 Budget and the 2019-20 Budget, also pre-election updates, the DTBNYA were not only large in the final year. The 2007 PEFO, released following the dissolution of parliament, revealed that the amounts were almost entirely for the government’s policy, The Utilities Allowance — increase and extend eligibility to include all recipients of Disability Support Pension, Service Pension, and Carer Payment.50

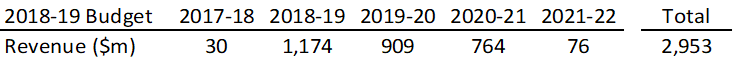

11. 2018-19 Budget51

An increase in revenue of around $1.2 billion for the budget year was included as DTBNYA at the 2018-19 Budget, decreasing in size over the forward estimates.

Components of the DTBNYA which were tax revenue would have been included in the forecasts for the relevant taxes, but components of non-tax revenue would have been included in the Contingency Reserve.

The Budget also included a $1.1 billion increase in expenses in DTBNYA, affecting 2020-21, with much smaller amounts for all other years.

The nature of these amounts and their relationship, if any, is unknown.

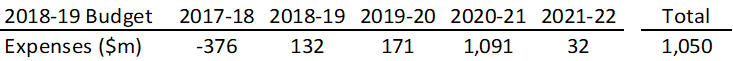

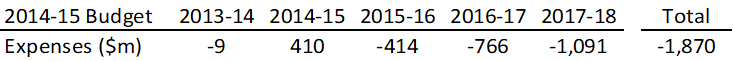

12. 2014-15 Budget52

At the 2014-15 Budget, DTBNYA reduced expenses by increasing amounts across the forward estimates, reaching nearly $1.1 billion for the 2017-18 year.

The subsequent 2014-15 MYEFO announced several policies which had been included as DTBNYA at the 2014-15 Budget, but they were all relatively small, leaving the amounts shown here largely unexplained. By the 2015-16 Budget, the Contingency Reserve amounts were almost zero (excluding the CBA), indicating the absence of remaining DTBNYA amounts. This may indicate that amounts for DTBNYA in the 2014-15 Budget were largely due to a decision to not proceed with some policies.

1. A ‘fiscal update’ is a release of one of the documents specified in the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998: the annual Budget, the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) and the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO). Governments sometimes release other updates in between these, but any measures announced are always repeated at the following fiscal update.

3. For example, the 2004-05 Budget (p. 6-31) included an allowance for the impact of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission's Living Wage Case Decision, released less than a week before the budget.

4. 2009-10 Budget Paper 1, p. 6-54.

5. In the 2023-24 Budget, this is Statement 6 of Budget Paper 1, where the Contingency Reserve is considered as a separate ‘sub-function’. In the forecast financial statements (Statement 10) the Contingency Reserve is allocated to various line items according to the details of the individual components, with the CBA allocated entirely to ‘Current transfers: personal benefits.’ The CBA is included in both the fiscal balance and underlying cash balance, while other provisions in the Contingency Reserve are allocated depending on their exact nature.

6. While Commonwealth budgets usually include lists of items that might be included in the Contingency Reserve, they are not required to provide details on what has been included in the Contingency Reserve. The Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998 does not provide guidance on the use of the Contingency Reserve.

7. Box 1 states that there are no 'actual' amounts for the Contingency Reserve. For several years up to 2008-09, however, the Contingency Reserve included expenses related to asset sales, which resulted in small 'actuals', and a larger amount of $589 million for 2006-07. Since 2009-10, the Contingency Reserve actual has been zero.

8. https://www.finance.gov.au/about-us/glossary/pgpa/term-contingency-reserve.

9. International Monetary Fund (2008), Fiscal Risks—Sources, Disclosure, and Management, p. 27, available https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2008/052108.pdf.

10. International Monetary Fund (2018), Austria Fiscal Transparency Evaluation, p. 57, available here https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/CR/2018/cr18193.ashx.

11. The 1984-85 Budget did not mention a 'Contingency Reserve' but included a 'Provision for Contingent Manpower Costs' of $60m in the forecasts for defence expenses only (Budget Paper 1, p. 82).

12. The 1987-88 Budget (Paper 1, p. 294) was the first update where the Contingency Reserve was explicitly identified, noting that the then $150 million Contingency Reserve was a reasonable provision to cover the uncertainty around estimates of increases in public sector wages and other allowances.

13. Different percentages are also used for the MYEFO, however these are simply adjustments to reconcile time passing. For example, the first forward estimate year at the 2020-21 MYEFO (2021-22) used a CBA percentage of 0.25 per cent - as roughly half a year had passed, the CBA needed to be reduced by an equivalent amount.

14. The CBA is typically estimated from preliminary budget estimates, so there can be small discrepancies when recreating the CBA using final aggregates. The CBA amounts are rounded to the nearest $100 million.

15. Answer to Question on Notice, reference F6, Review of the conservative bias allowance, p. 2, available here Finance and Deregulation portfolio – Parliament of Australia (aph.gov.au).

16. 'Demand-driven' programs have their funding determined by the number of users, and have no fixed limits on the number of people who can access the program. For more information, see the PBO's Online Budget Glossary.

17. Answer to Question on Notice, reference F6, Review of the conservative bias allowance, p. 2, available here https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Senate_estimates/fapactte/estimates/sup1011/finance/index.

18. For further background on MTEF's see OECD Medium Term Expenditure Framework.

19. In the 2023-24 Budget, these are Table 1 (p. 6) for receipts and Table 2 (p. 54) for payments. DTBNYA is usually the last item in the tables.

21. These measures for new listings may have both a revenue and expense component, depending on the nature of the contract. For example, if the government purchases medicine at a discount from the market price, then this may be reported in the budget as a purchase at the market price, recorded as an expense, and a rebate from the seller, recorded as revenue.

22. In some cases, the policy may have been partly included in a previous update as DTBNYA, or partly announced in a previous update, in which case the amounts may not be zero.

23. The detailed funding profile can sometimes be found in the Portfolio Additional Estimates Statement (PAES). For the example included in Box 5, the funding profile for this measure can be found on page 56 of the Health PAES 2018-19.

24. Except for policies which only affect tax revenue, which are never allocated to the Contingency Reserve.

25. For example, the 2019-20 Budget announced 37 measures which had been partly or wholly included in DTBNYA in previous budget updates. www.aph.gov.au/-/media/Estimates/fpa/bud1920/tabled_docs/finance/TabledDoc15_Finance_DTBNYA.pdf.

26. While accrual terms are used here, cash definitions have been the status quo for Budget Paper 2 since the 2020 July Economic and Fiscal Update. For more information on cash and accrual accounting, see the PBO’s Online Budget Glossary.

27. All undisclosed items in the Contingency Reserve are unwound prior to a general election, With the exception of policies that have been announced but whose costs have not been published.

28. 2022 PEFO pp. 7-8.

29. In earlier budgets, a general provision for wage increases served a similar function to, but was not specifically, the CBA. For example, the 1986-87 Budget included $125 million for the provision for contingency salary and related costs (non-Defence) - see 1986-87 Budget, p. 75.

30. As the budget is generally released in May, the outcome year is an estimate and not the final outcome.

31. Program specific parameter variations are published in reconciliation of expenses tables in budget updates (see Table 2 of this report).

32. 2021-22 MYEFO, p. 202.

33. 2021-22 Budget Paper 2, p. 50.

34. Finance Minister Simon Birmingham reported that the budget documents "haven't detailed how much money is budgeted [for mRNA vaccines] because there are two very sensitive commercial negotiations that have to be pursued there. […] But it is baked into the Budget bottom line. It's part of the contingency reserve in the Budget." https://www.financeminister.gov.au/transcript/2021/05/12/sky-news-live-first-edition-peter-stefanovic.

35. For example, investment in manufacturing of mRNA vaccines is on p. 134 of Budget Paper 2 in the 2021‑22 Budget.

36. Confirmed by the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources through a question on notice, available at https://www.aph.gov.au/api/qon/downloadestimatesquestions/EstimatesQuestion-CommitteeId8-EstimatesRoundId11-PortfolioId34-QuestionNumber1.2018-19 MYEFO, p. 111.

37. 2018-19 MYEFO, p. 111.

38. Forecasts for total growth in Compensation of Employees were unchanged or slightly higher at the MYEFO (p. 46) compared to the previous Budget (p. 5-9), while growth in Gross income tax withholding was significantly reduced in the same years (p. 5-17 of the 2018-19 Budget compared to p. 44 of the MYEFO). The MYEFO reported that "excluding policy decisions, individuals taxes have been revised up by $4.1 billion (1.9 per cent) in 2018-19 and $13.8 billion over the four years to 2021-22." (p. 46).

39. 2023-24 Budget Paper 2, p.54.

40. This is the first mention of the Nuclear-Powered Submarine Program in the budget updates however it may have been provisioned for at previous budgets. The 2023-24 MYEFO included further funding for this program, however, these costs were met from within existing resources of the Department of Defence.

41. 2020-21 Budget Paper 2, p. 45.

42. 2019-20 Budget Paper 2, p. 45.

43. 2019-20 Budget Paper 1, Statement 5, p. 5-43.

44. The 2019 Pre-Election Fiscal Outlook, published two weeks after the Budget, noted that "Consistent with past practice, the DTBNYA lines in Budget Paper 2: Budget Measures, included the reversal of some DTBNYA items from previous budget rounds."

45. 2016-17 Budget Paper 2, p. 61.

46. The size of these provisions is also very similar, assuming that the previous year's estimate carried through to the final year. If the policies comprising the DTBNYA of $502 million in 2018-19 were to continue to 2019‑20 at a similar size, in both budgets the additional DTBNYA in the final year reduced expenses by around $2.5 billion.

47. 2023-24 MYEFO, p. 213.

48. 2022-23 Budget (March), p. 749.

49. 2007-08 MYEFO, p. 74.

50. 2007 Pre-Election Fiscal Outlook, p. 6.

51. 2018-19 Budget Paper 2, pp. 6 and 68.

52. 2014-15 Budget Paper 2, p. 47.